|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

MERCEDES — Last August, water levels at Falcon International Reservoir dropped to just 9%, the lowest in the manmade lake’s 70-year history.

Levels at Amistad International Reservoir 273 miles to the north weren’t doing much better as they hovered around 30%.

The two waterways supply fresh water to millions on both sides of the U.S.–Mexico border via the Rio Grande.

As scorching heat and prolonged drought battered the Rio Grande Valley and the northern Mexican states of Tamaulipas and Coahuila last summer, officials began to make entreaties to the Mexican federal government: release water.

Release water, please.

That’s because the Rio Grande is primarily fed via six tributaries that wend their way east from the mountainous deserts in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. But those waters are held back from reaching the border by eight dams.

However, a 1944 water sharing treaty between the two countries obligates Mexico to regularly deliver water to the United States from those tributaries.

The treaty earmarks two-thirds of those downstream flows for Mexico’s own people in Tamaulipas and Coahuila, while the remaining one-third is meant for the U.S.

Over the course of five years — the span of a single treaty “cycle” — Mexico is supposed to deliver 1.75 million-acre feet — or more than 570 billion gallons — of water to the United States.

But cycle after cycle, Mexico has fallen behind on timely deliveries, waiting instead until the eleventh hour to fulfill its obligations.

It’s a practice that harms not only water consumers in the U.S., but those in northern Mexico, as well.

And despite the earnest pleas from water users and officials on this side of the border, Mexico did not release any water last year.

That decision has had very predictable consequences.

In February, the Rio Grande Valley Sugar Growers Association announced that the consistent lack of water available to irrigate their tens of thousands of acres of farmland had delivered a death blow to their industry.

After 51 years in operation, the Valley’s sugar legacy had come to an end.

In the aftermath, cries from local officials to Mexico to release water have gone from “please,” to “now.”

But again, American leaders have seen little budging from Mexican officials.

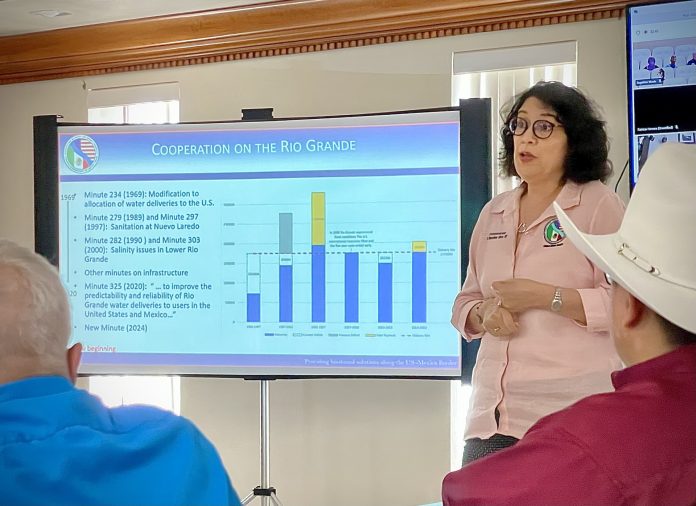

“I have a lot of friends, but hijole, it’s getting tough,” Maria-Elena Giner, commissioner of the U.S. International Boundary and Water Commission said during a meeting with water officials and experts in Mercedes Tuesday evening.

The IBWC, in conjunction with its Mexican counterpart, La Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas, or CILA, are responsible for administering the water sharing treaty, including tracking compliance with the treaty.

Since her appointment as IBWC commissioner in 2021, Giner has worked tirelessly to get the Mexican government to fulfill its treaty obligations.

The current five-year treaty cycle began in October 2020. Since then, however, Mexico has continued its history of delaying deliveries.

Four years into the current cycle and Mexico has delivered just slightly more than one year’s worth of water, or 382,000 acre-feet, to the Rio Grande.

“They delivered their water, historically, up until the ’92-’97 first five-year cycle … just with wild water,” Giner explained.

She described “wild water” as “whatever spilled over the dams.”

And therein lies part of the problem.

For American officials, treaty compliance means delivering water, period — whether that means allowing storm water to overspill Mexican dams and flow downstream, or by Mexico intentionally opening dam spill gates to release the water.

Mexican officials, however, interpret the treaty differently.

“There are very few instances where Mexico opened their dams” in order to fulfill its treaty obligations, Giner said.

Since her appointment as commissioner, Giner has worked to build a compromise in the two countries’ discordant interpretations of the treaty.

Giner had pinned a lot of hope on what’s called a “minute” — an amendment to the treaty guidelines.

For nearly a year, she, the IBWC and CILA officials had worked to craft the language of the minute, which would have given Mexico more flexibility in how it complied with the treaty.

“I’m really pushing back in the sense that we really need to come to an understanding,” Giner said.

She wants Mexico to acknowledge that their practice of relying on “wild water” is no longer sufficient.

“Right now, where we’re at with the water levels, it is a very dire situation and the likelihood of spillage … is starting to become very, very small,” Giner said.

The IBWC and CILA had expected officials from both nations to come together to sign the new treaty minute in December.

But that never happened.

State officials in Chihuahua and Tamaulipas had balked at some of the terms of the minute’s language, which would have given Mexico the ability to earmark up to 100% of the six tributary flows to the sole ownership of the United States, rather than just one-third.

On the eve of the minute’s signing, the two Mexican state governments took out hefty advertisements opposing the minute in Mexico City media.

“(The Mexican federal government) asked us to wait until February to let them have those meetings with Chihuahua and Tamaulipas, and the last we heard, those meetings had not occurred,” Giner said.

“Given that, this has now accelerated to higher levels,” she added.

Giner was speaking of conversations that have begun within the U.S. State Department, and even within the National Security Council, over Mexico’s continued failure to abide by the treaty.

But conversations are happening outside the Beltway, too.

Within the last week, U.S. Rep. Vicente Gonzalez, D-Brownsville, met with Mexico’s Office of Foreign Affairs to discuss the issue.

And while Giner was speaking with stakeholders at the IBWC’s offices in Mercedes Tuesday night, state Rep. Terry Canales, D-Edinburg, announced that the Valley delegation of lawmakers had sent a letter urging Secretary of State Antony Blinken to take action on the water crisis.

Further, next week, Valley leaders will be traveling to Washington D.C. to meet with State Department officials, as well.

Those discussions are in addition to the regular pressure Giner has been applying here and in Mexico herself.

“Until we see that authorization, we are still pursuing that pressure,” Giner said.

“We can’t just sit here and let the next year-and-a-half go by with our arms — con las manos cruzados,” she added a moment later.

As for why Mexico is continuing to drag its feet this cycle, the commissioner opined that Mexico’s upcoming federal elections may be playing a part.

Mexican citizens will be electing a new president to a six-year term come June 2 and many see outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador as a lame duck.

“I think the hangup with the election cycle … any kind of movement is gonna cause backlash,” Giner said.