After Mexico has spent the last 10 years struggling to meet its water delivery obligations to the United States, officials here have begun to brainstorm ways to mitigate the potential for future water shortages.

The search for solutions has become ever more pressing as Mexico is once again beginning to falter on making the water deliveries to the Rio Grande as required by a 1944 treaty between the two nations.

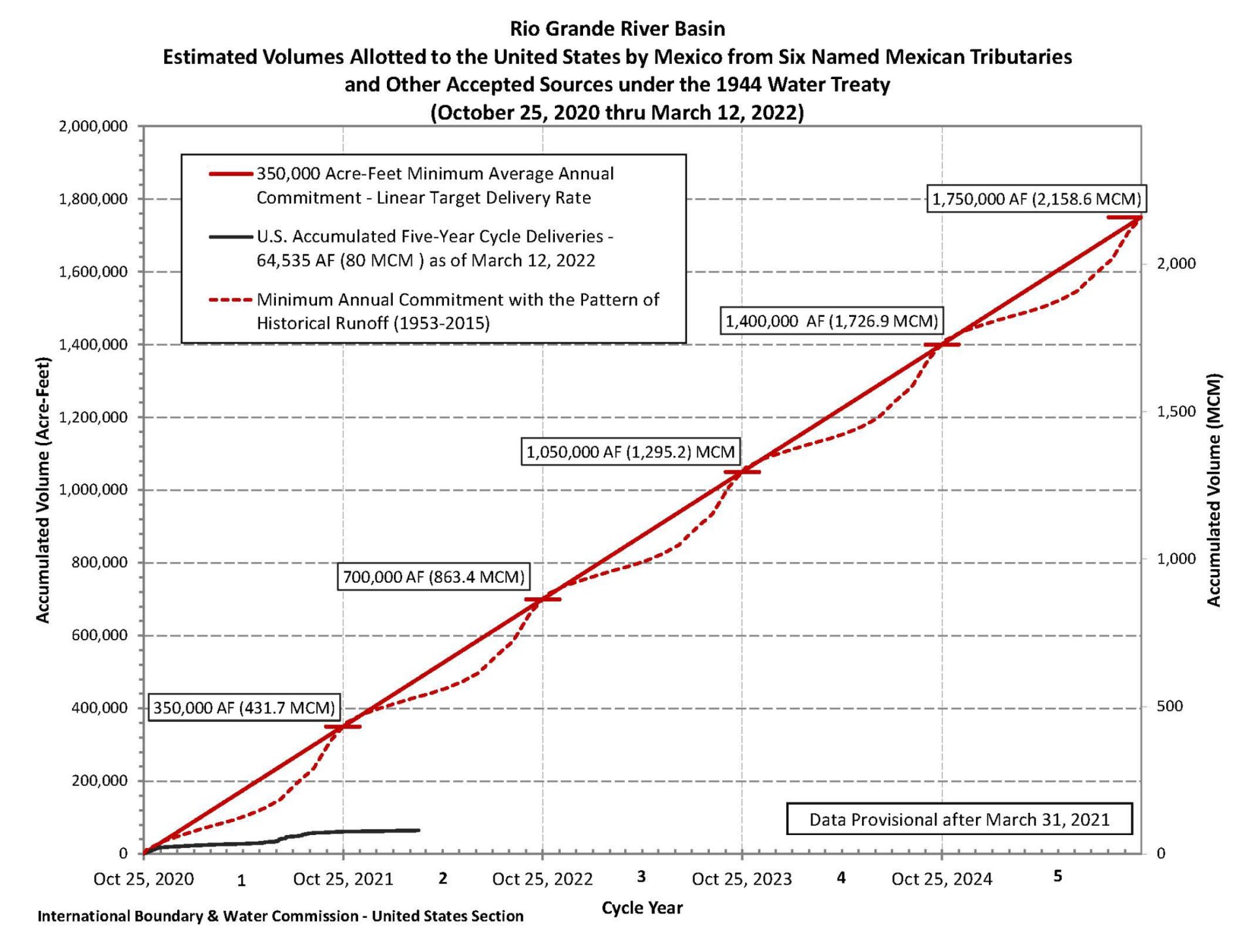

Under the terms of the treaty, Mexico is obligated to deliver to the U.S. some 1.75 million acre-feet of water every five years from the six tributaries that feed into the Rio Grande.

Ideally, Mexico would deliver 350,000 acre-feet of water every year until the ledger of a five-year cycle resets in late-October.

The most recent five-year cycle ended in October 2020. Mexico nearly defaulted on its obligations, but made good just before the deadline by transferring national ownership of water it had stored in Amistad and Falcon international reservoirs to the U.S.

In so doing, Mexico narrowly avoided violating a clause within the treaty which prohibits two back-to-back cycles from ending in a deficit. In the previous cycle, from 2010 to 2015, Mexico’s water deliveries fell short by more than 263,000 acre-feet.

RUNNING SHORT

One year into the current cycle, however, data from the International Boundary and Water Commission shows Mexico is already far behind on its deliveries once again.

“This is the bad news about where we are right now in the cycle,” Sally Spener, secretary to the IBWC, said during a webinar Thursday afternoon.

Spener was referring to a line graph illustrating what ideal water deliveries look like versus what the actual deliveries have been.

The first line — a hypothetical illustration showing Mexico releasing equal volumes of water every day for five years — inclined upward in a straight path to the right.

The second — reflecting seasonable variances — inclined steadily to the right with gentle undulations illustrating the effects of wetter summers and falls juxtaposed with drier winters and springs.

But the last line — the one showing the deliveries Mexico has made during the first year of the 2020-25 cycle — lay nearly flat in its progression to the right.

“That shows that water deliveries are actually very poor in the current cycle,” Spener said.

Indeed, between October 25, 2020 and March 12 of this year, Mexico has only delivered about 65,000 acre-feet of water.

That’s about 18% of the water the U.S. expects to receive in one year.

PART OF A PATTERN

The “poor” water deliveries thus far illustrate how the two countries have spent the last 12 years playing a delicate balancing game with a resource that is becoming increasingly scarce.

“What can we do to promote the long term sustainability of the Rio Grande Basin?” Spener asked.

“With climate change, we may experience worse drought, or longer drought, or drier soil moisture conditions. We may also experience more hurricanes that cause localized flooding, but hopefully, they’ll also help fill up the reservoirs,” she said.

The treaty was crafted with tropical weather in mind — banking on hurricanes to strike the Texas-Mexico coastline and replenish the Rio Grande watershed.

But, that hasn’t happened.

And across northern Mexico and the American Southwest, a long-term drought is fueling what has been called the driest period in 1,200 years, further exacerbating water shortages.

La Boquilla Dam, the largest reservoir on the Conchos River, is at just one-third capacity, Spener said.

Carranza Dam, on the Salado River, is at just 13% capacity. The Salado is Mexico’s second largest contributor to the water deliveries.

SEEKING SOLUTIONS

After 2020 nearly ended in another deficit, the IBWC and its Mexican counterpart, La Comisión Internacional de Límites y Agua, formed several so-called “workgroups” to analyze the issues and come up with potential solutions.

On this side of the border, IBWC formed the Rio Grande Hydrology Workgroup and tasked its members with creating a computer modeling system that will allow the agency to test out scenarios and potential solutions virtually.

“This is going to be a really powerful tool so we can task different strategies to improve the predictability and reliability of Rio Grande water deliveries to users in both countries,” Spener said.

The IBWC has also teamed up with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, and others to identify American water priorities they would like to run through the model to gauge the efficacy of potential solutions.

However, the IBWC has yet to receive a similar set of priorities from their Mexican counterparts.

Despite that, American officials have been able to identify areas where inefficiencies can be reduced, such as a provision in the treaty that requires that water released from Mexican reservoirs be divided into split ownership between Mexico and the U.S.

“Currently, because of the one-third, two-thirds requirement of the treaty, if Mexico wants to deliver 100,000 acre-feet to the United States, they actually have to release 300,000 acre-feet from their reservoirs,” Spener explained.

The solution proposes allowing Mexico to assign 100% ownership of a water release to the U.S. outside of the narrow exceptions that currently only occur at the 11th hour of a looming treaty deadline.

Another proposal involves creating an aqueduct between Falcon International Reservoir and Matamoros, Mexico.

The city requires 77,000 acre-feet of water annually, but in order for that volume of water to arrive in Matamoros, some 255,000 acre-feet of water must be released from Falcon Dam.

Like an ice cube melting in the heat, that extra 178,000 acre-feet of water becomes “conveyance loss” as it travels more than 130 miles downstream.

Another option would be to build a desalination plant at El Morillo Drain, which diverts some 300,000 tons of salt from Mexican runoff away from the Rio Grande. Desalinating the runoff would allow for the reclamation of 83,500 acre-feet of water per year.

One proposal that has been met with strong resistance in the past would be to allow Mexico to deliver water from the San Juan River to U.S. water coffers.

But that option is unpalatable to farmers and politicians alike because the San Juan River joins up with the Rio Grande south of Falcon Dam.

Without a place to store it, the water is wasted as it flows uselessly to the Gulf of Mexico.

The IBWC continues to explore other potential solutions to the looming water crisis and how those solutions may impact each country differently.

“Again, we need to be smarter about how we use our water so that we can have a more sustainable future for the Rio Grande,” Spener said.