“They had more years in them, they had more years and they robbed us. Those people who don’t social distance, they robbed us of the ability to hold their hands, to say goodbye. They took that away from us.”

Doreen Morgan

Daughter to A.C. “Beto” Jaime and Dora Garcia Jaime

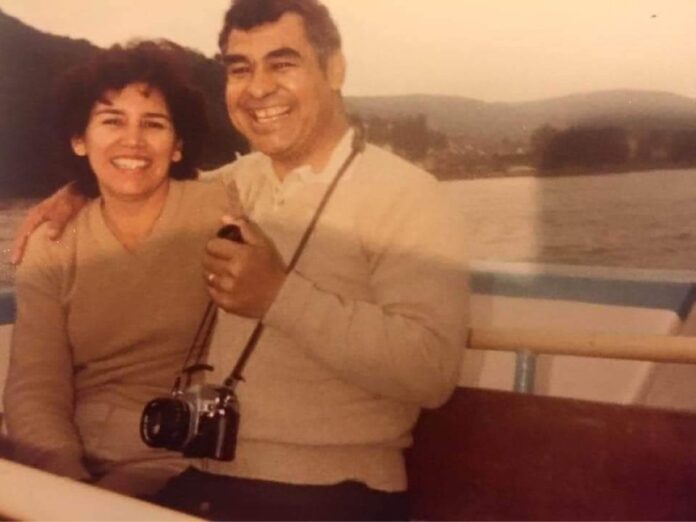

His life extinguishing with each breath, Adalberto Casares Jaime used what little air he had left begging to be with his wife. Those pleas were heard but impossible to grant, and he died on July 23 in the company of strangers. He died from COVID-19.

Then on July 25, Dora Garcia Jaime, the other half of what their children describe as a storybook romance, succumbed to the same disease that has now claimed more than 1,000 people in the Rio Grande Valley.

They were both 84, and they had plenty of life left to live if not for the novel coronavirus.

To some, it’s a tragic tale. To their children, it’s a nightmare knowing their father’s final moments were spent worrying for his beloved Dora, who at the time was in a hospital hallway because there wasn’t enough room — an all too common occurrence at local healthcare institutions overwhelmed with COVID-19 hospitalizations.

They’re even uncertain if their mother, who was also battling Alzheimer’s, was aware of the circumstances and of whom she was with, and without.

Doreen Morgan, the fifth of the Jaimes’ six children of four boys and two girls, said her parents had such an endearing dependence on one another that they vowed to never be apart, even in death. And now, knowing their time came without the comfort of being together is too much to bear.

Such thoughts haunt the 49-year-old Washington resident and native of Pharr, who lashed out Wednesday, the eve of her parents’ funeral, at those who refuse to social distance or wear masks — decisions she believes cost them their lives.

“The funeral is tomorrow, and here we are, six peas in a pod and we can’t even be close to each other, to grieve with each other. We have to be so many feet away, but you want to hold each other, cry on your siblings’ shoulders. It’s terrible … it’s terrible,” Doreen said as she wept Wednesday evening. “And why: Because somebody didn’t want to social distance, because somebody didn’t want to wear a mask? They had more years in them, they had more years and they robbed us. Those people who don’t social distance, they robbed us of the ability to hold their hands, to say goodbye. They took that away from us.”

Both angry and at peace, grateful and aghast, Doreen’s emotions ran the gamut of grief.

One moment she was joyful in recalling the memories and legacy they left behind, and the next she was pained and angry at the circumstances. Laughs turned into sobs and sobs turned into laughs.

At the time she spoke with The Monitor, for instance, she was gathering her husband and children to visit the streets in Pharr that were named after a comment her father, who was known as both A.C. and Beto, made when he was the city’s mayor in the 1970s.

“I heard a story once that he was so swamped that when they asked him what he wanted to name these streets, daddy said, ‘I don’t care: This way. That way. Every way.’ And that’s what they named the streets, so I’m going to take my kids and husband to go and see those streets,” a delighted Doreen said.

But the tone quickly shifted to despair as she remembered the last conversations her family had with their father.

There was one particularly poignant moment that broke Doreen’s heart to recall.

“He tried to take care of her. He even asked my sister if she thought he had one more night; if he would make it through the night because he wanted one more night with her,” Doreen said as she broke down again. “He didn’t want to leave her, and he was trying to take care of her even at the time the ambulance took him.”

She said her dad did all he could to protect themselves from the disease that has spread to nearly 35,000 people across the Valley, even installing hand-sanitizing stations at their home for visitors.

“This really stinks,” Doreen said in frustration. “When COVID came he knew the risks, and was always telling people that if they’re careful and stay apart, we may all survive this.”

But not everyone was careful, and people did not survive.

Acknowledging such losses to the novel coronavirus, U.S. Rep. Vicente Gonzalez, D-McAllen, believes practicing public health precautions should have long been a matter of state mandate and not personal responsibility alone.

“I can’t agree with her more,” Gonzalez said about Doreen’s frustrations regarding mask wearing and social distancing. “Leadership at the state and federal levels failed this country and the state, and we’re losing people unnecessarily because leadership has not emphasized and supported the ideas that help save lives, that the CDC has recommended. As you know, our governor for four months didn’t require a mask, our president still doesn’t wear masks in public … and it’s a very negligent message to the community who are losing people on a daily basis.”

It should be noted that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were not requiring the use of masks when the pandemic first reached America. It wasn’t until late March that, in an interview with NPR, CDC Director Robert Redfield said the agency was reconsidering its position.

Still, all Doreen knows is that her parents are dead, and it could have been prevented.

It wasn’t a point, however, that she dwelled on for too long on Wednesday, and instead called it an honor to speak of her parents being the salt of the earth, the kind of people who forgive.

The kind of people COVID-19 has taken from Valley families.

A.C. worked as a CPA and served as Pharr’s first Hispanic mayor, having helped his administration ease racial tensions in the community during his tenure in the 1970s. He also spearheaded racewalking opportunities for local youth and was instrumental in obtaining a presidential permit for the Pharr-Reynosa International Bridge, one of the main trade corridors in the U.S.

When he was young, his football coach had to buy him shoes because his family couldn’t afford them. In fact, his sister used to make their clothes from potato sacks.

Dora was a graduate of Pharr-San Juan-Alamo High School and Pan American College and worked as a licensed vocational nurse at McAllen General Hospital. She was active at Our Lady of Sorrows Catholic Church in McAllen, and loved working together with A.C. at his firm.

She was reserved in public but funny at home, preferring to avoid the public attention that came with her husband’s mayoral office, and instead dedicated her life to being the nurturer in the family whose laugh resonated and was passed on to her children.

They believed in God and taught their children patience, acceptance, faith, and the value of hard work.

Their children followed in their footsteps and went on to become public servants, accountants, a chaplain, and an advocate for LGBTQ rights. A.C. and Dora’s kids are also active in the military community, volunteer at their churches, and help coach youth sports.

And now they’re gone, two losses among 1,149 who have died due to COVID-19 in the Valley.

A licensed psychologist and associate professor in the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley’s Department of Psychological Science, Alfonso Mercado said Thursday that a community suffering fatalities of this magnitude can be affected in varying ways, but specifically pointed to the stress burdening entire communities.

In recently speaking with members of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, Mercado also identified mental health needs with Latino children in the U.S. as it relates to losing their elders.

“These are compound effects of multiple crises that are currently happening in our society, and really globally,” said Mercado, who in addition to his work in the UTRGV School of Medicine Psychiatry and Neurology Department also serves as the president-elect designate for the Texas Psychological Association. “Currently, and as we know during the pandemic, there are so many stressors from family members dying. We’re looking at the health deterioration of our loved ones, of our neighbors and our friends. We’re not only living through the pandemic of COVID-19, but many and I believe we’re living through the pandemic of mental health.”

In his research setting, which includes minority, immigrant and historically underserved communities, Mercado said comorbidity is prevalent within the same groups of people who are also unable to stay home due to the nature of their work.

Emotional and psychological suffering then pervades.

“Unfortunately in South Texas, we are an underserved community regarding health care, and COVID-19 has opened the reality of the disproportionate rate of people it’s affecting — people of color, Latinos, many immigrant groups and undocumented groups. They don’t have the luxury of sheltering at home, because they’re the invisible essential workers. We don’t see the work they’re doing,” he added. “As a psychologist here in the Valley, and doing research and working with the Latino population for most of my career, this is very concerning where people are living through multiple crises at the same time.

“We need to practice healthy eating, healthy sleeping, and healthy activity with family while staying at home. Unfortunately the death rates aren’t going anywhere, and a lot of families are going to continue to suffer seeing their loved ones pass due to COVID-19.”

According to the congressman, the deaths in the Valley have already left an immeasurable impact.

“I had the opportunity to meet the mayor and his wife during my first campaign, and they were very unassuming people,” Gonzalez said of A.C. and Dora. “His tenure opened eyes to the possibility of being a Hispanic mayor in the Valley, and he was a trailblazer for many who came after him. So clearly it is impacting the legacy of the Valley. So many people who we rely on for their history and their advice are leaving us.”

That guidance for Doreen and her brothers and sister came in the form of wisdom: to treat everyone the same way in any setting, “from janitors to CEOs,” to be forgiving and empathize, to work hard and be modest with blessings, and that everyone deserves a smile.

Perhaps a more profound legacy is teaching their children how to love unconditionally.

“That was a great light that went out,” Doreen said of her parents’ deaths. “I know everybody probably says this, but nobody can fill their shoes. There will never be another A.C. and Dora.”