An Afro-Latino Spider-Man may have won the hearts of critics and audiences alike with “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse,” but the depiction of Miles Morales as the famous web slinger is a relatively recent phenomenon — people of color telling their own stories in mainstream comic books.

In examining the representation of Mexican-Americans in comics around the Chicano movement, Jose Alaniz said the main takeaway was that even progressive stories were told through a Caucasian lens.

Alaniz, a professor in the department of Slavic languages and literatures at the University of Washington in Seattle, spoke in Edinburg on Tuesday about Mexican-American representation in comics from the 1950s to the 1980s.

The presentation was part of FESTIBA, the Festival of International Books and Arts hosted by the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

He went through two examples of Mexican-American depictions, the first from a 1954 comic book entitled “The Whipping” from EC Comics — a publishing company known for their stories of horror and crime.

“But they were also politically charged,” Alaniz said. “They were all about critiquing post-war America and its hypocrisies, including its racism.”

The story in “The Whipping” tells of a white man named Ed from a typical American town and his outrage at discovering his daughter is dating a Hispanic man.

The character of Ed utters typical racial slurs throughout the comic and in his anger, spreads lies throughout the town that the Hispanic man, Luis Martinez, tried to rape his daughter. This resulted in the town’s men rallying to attack Luis.

During a dark night, dressed in white robes, the men beat Luis to death only to discover afterward that the person they killed was Ed’s daughter.

That shock ending, Alaniz said, was typical of EC Comics and, in fact, was very similar to “The Guilty,” a comic released two years prior featuring a black man.

“The power, the fate of the Mexican-American, as for the black, is really not in their own hands. It’s in the hands of the whites,” Alaniz pointed out of the two comics. “So whether to kill them or whether to spare them, it’s going to be put to the white majority.”

Within the context of the 1950s, Alaniz said it was good the comic was shining a light on discrimination but pointed out the Mexican-American character had very little voice.

“It’s still very much oriented to: ‘What can we, white people’ — the presumed reader is a white reader — ‘what can we do to kind of not be terrible people?’” Alaniz said.

The second example was a Superman comic published in 1972, after the rise of the Chicano movement, called “Must There Be a Superman?”

The comic grapples with whether it is possible for Superman to help humanity too much, hindering their ability to fend for themselves.

In the story, Superman travels to a migrant camp in California where a farmworker is dealing with an abusive patrón.

Through talking to a young, migrant boy, Superman realizes his own life story is similar to an immigrant’s story, having come to Earth from his home planet, Krypton.

When an earthquake hits, Superman saves the migrants and even helps them rebuild their homes, but declines to help them with their patrón.

Alaniz pointed out that the question of whether Superman was making people less self-reliant was one that could have been raised a lot earlier in the comic’s history.

“I think it’s not a coincidence that this question now, this kind of story, gets explored in 1972, precisely at the moment when you do have a civil rights’ movement that the comics are reacting to,” he said, adding that at this time, legislation was being drafted and passed to support historically oppressed people.

That representation of Mexican-Americans as farmworkers was typical to how they were shown in comics around that time to the extent they were shown at all, Alaniz said.

Since then, though, there’s been a growth of Latinos in the comic book industry in general, whether as artists or writers.

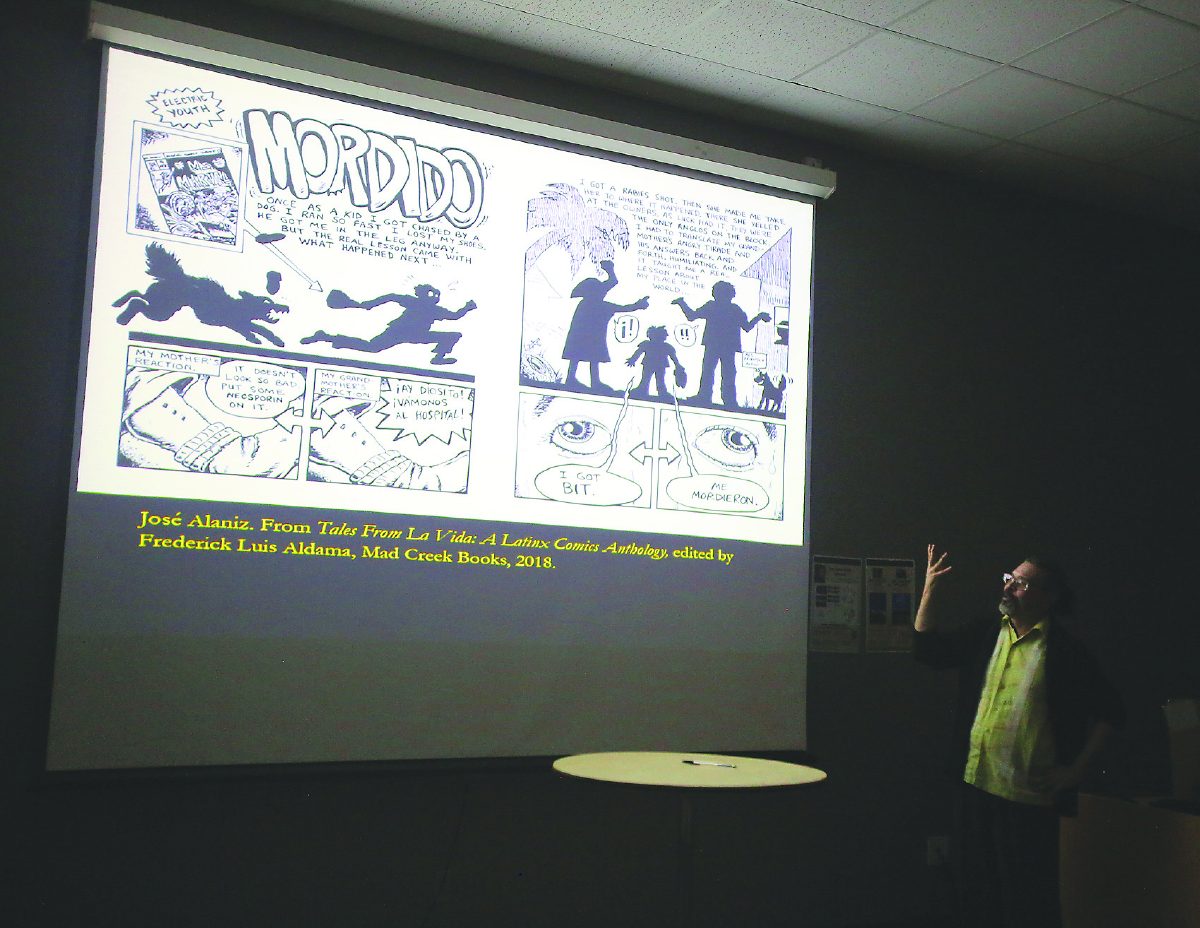

Alaniz pointed to a book that he’s featured in, “Tales from la Vida: A Latinx Comics Anthology,” that only features work from Latinos.

“It’s self-representation, that’s the big difference,” he said.

As far as characters, Morales, the Ultimates version of Spider-Man, remains the most well-known example of a Latino.

However, Alaniz expressed concern over the commodification of diversity and possibly making the practice of including people of color a new “style.”

“You could completely make it a total rainbow world. That wouldn’t make racism and discrimination go away,” he said, adding that this could create the false belief that racism is over, allowing it to continue existing, hidden.

“It’s not over,” Alaniz said. “It’s never done.”