Even before the COVID-19 pandemic slowed down court systems across the country, the immigration court system had been sagging underneath the weight of hundreds of thousands of people awaiting their day in court.

Now, as the number of backlogged cases has swelled to more than 1.2 million, Rep. Henry Cuellar, D-Laredo, is hoping new legislation he recently introduced will help alleviate the problem by funding the addition of 100 new immigration judges throughout the Southwest.

That figure is in addition to the 315 immigration judges who have already been greenlighted by Congress since Cuellar became a member of the House Committee on Appropriations in fiscal year 2016, he said.

“Just in Texas, there’s 189,000 cases that are backlogged,” Cuellar said during a Zoom videoconference with reporters Wednesday afternoon.

“The average wait across the nation is 759 days for those cases to be heard. And in the state of Texas, it’s higher at 793 (days),” he said.

The proposal has already gained approval in the U.S. House of Representatives and now moves to the Senate, Cuellar said.

Though Cuellar couldn’t speak to how many of those judges would be appointed to the Rio Grande Valley, he did say eight new positions will open in Laredo, which — as of now — is the only place along the border to have zero immigration judges.

The eight Laredo judges are part of a previously approved appropriations bill, the congressman said, adding that their courts won’t become operational until the summer of 2021.

But Cuellar is hoping to furnish more than just additional judicial officers. The congressman said another issue hampering immigration court proceedings is a massive lack of resources — both in terms of judges, but also in terms of physical courtroom space, as well as the technology needed to facilitate remote court hearings in the age of COVID-19.

In many jurisdictions, there are more judges than there are courtrooms, forcing the courts to play a game of musical chairs where “floating” judges have to wait for a courtroom to be empty before they can get to work.

“That’s not the way to run the immigration system,” Cuellar said.

“I’ve added money for new courtrooms because, right now, there are more judges than courtrooms and, again, we’ve gotta be able to administer this correctly,” he said.

Furthermore, once the pandemic began sweeping the country in March, several immigration judges were sent home on what was labeled “weather related leave/reasonable accommodation,” Cuellar said. Some of those judges have not held a single court hearing since.

Others were sent home without the technological equipment necessary to hold court remotely, such as laptops and computers.

With immigration court dockets already delayed by years, Cuellar criticized that lack of resources for exacerbating an already floundering system, especially while taxpayers continue to foot the bill.

He further lambasted the inability of the immigration court system to keep up with its cousins in the federal judicial system, where federal judges have continued to hold criminal and civil proceedings throughout the pandemic, albeit at a reduced pace.

“If the federal judiciary system can do it, then definitely, the immigration judges should be able to do that, too,” Cuellar said.

It was a criticism shared by local immigration attorney Carlos M. Garcia, who on Wednesday spoke of the technological inadequacies of immigration court.

“Realistically, though, the immigration courts need to update their technology,” Garcia said.

“Every court — state court, federal court — they all seem to have adapted fairly quickly to video hearings and technology where you can work remotely. And immigration court is lagging,” he said.

As a result, Garcia has been obligated to represent his clients in person at detention centers that have quickly become rife with clusters of COVID-19.

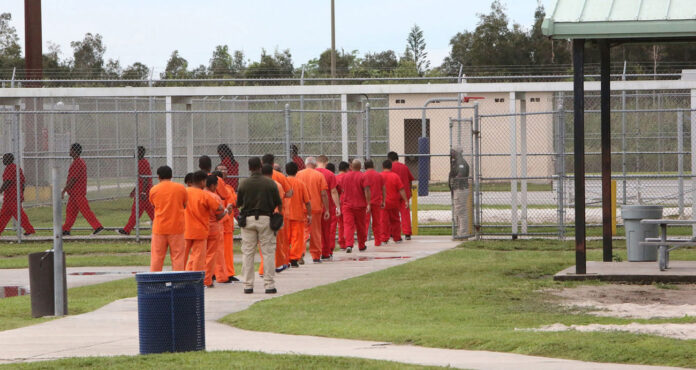

At the Port Isabel Detention Center, for example, some 12 staffers and 84 detainees have tested positive for the virus, according to data released by Cameron County officials Tuesday.

And in June, officials from the private prison contractor, The GEO Group, confirmed that a detention officer at the East Hidalgo Detention Center in La Villa had died of the disease, while several more had tested positive.

“Not to my knowledge have immigration courts been able to proceed with video hearings where you can talk and see the judge and the opposing attorney via video, unlike the federal and state courts have,” Garcia said.