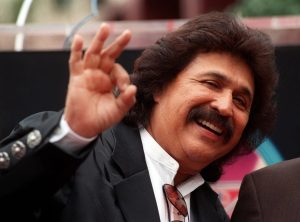

SAN BENITO — Capping years of work, the San Benito Historical Society is placing a state historical marker at hometown hero Freddy Fender’s family home, honoring the Grammy Award-winning singer who’s the top attraction in the city billed as the birthplace of conjunto music.

On Saturday, organizers are planning a ceremony to unveil the Texas Historical Commission’s plaque at 143 Freddy Fender Lane, the two-story brick house where family members of Baldemar Huerta, the singer who became known as Freddy Fender, have raised generations.

“With the cooperation of the city of San Benito, we are proud to add one more historical marker to our town’s unique heritage — and another attraction for visitors,” Sandra Tumberlinson, the historical society’s co-founder who worked months on the project, stated. “We are grateful to the Huerta family and Freddy’s cousins, who graciously volunteered to host the state marker on their property.”

In 2013, a Cameron County Historical Commission committee, with local historian Norman Rozeff serving as chairman, worked to complete the plaque.

“Known as Freddy Fender, or El Bebop Kid (the Mexican Elvis Presley), Baldemar Garza Huerta achieved great success as a Tejano, rock and country singer for over 50 years,” the marker reads. “Fender’s music appealed to a wide audience with his emotional and experience-driven songs. His fame also allowed him to contribute to many charitable causes. Freddy Fender played for U.S. presidents and had a star placed on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Even with his fame, Fender never forgot his humble roots and hometown. One of San Benito’s favorite sons, he is buried in the San Benito City Cemetery.”

On Oct. 14, 2006, he died at his Corpus Christi home, months after being diagnosed with lung cancer, at age 69.

Keeping legacy alive

Next door to the family home, Joe Mendez, Fender’s youngest brother, recalled the early years of a roller-coaster career spanning five decades in which the acclaimed tenor rode to the top of the pop, country and Tejano charts and onto the big screen in movies like 1988’s “The Milagro Beanfield War,” while singing the haunting title track in the 1982 film “The Border.”

“It’s long overdue,” Mendez, 77, a retired route salesman, said. “The family feels great with some of the things Freddy did to make San Benito a recognized town.”

For the ceremony, Marla Huerta, the youngest of Fender’s five children, is planning to travel from Murrieta, Calif., to speak on behalf of her family.

“It’s amazing,” Huerta, 42, who works for Disney, said. “I love to see his hometown keeping his memory alive. It’s an honor to know they care so much to keep his legacy alive. It kind of brings tears to my eyes.”

More than 20 years ago, she shared her life with her father.

In 2002, she gave him her right kidney after hepatitis C infected him.

“He was reluctant because I was the youngest but I didn’t even think about it. I just did it,” she said. “It was an honor. It was an opportunity to show him how much I love him and how important he was in my life.”

Family home

On June 4, 1937, Baldemar Garza Huerta was born to Serapio and Margarita Garza Huerta, the oldest of nine children.

In San Benito, he grew up behind 550 Biddle St., his home razed long ago.

“My dad loved San Benito,” Marla Huerta said. “It was a big part of his life and it continued to be a big part of his life.”

Mendez, who was adopted, was 16 when he found out he had a brother who was a big star.

“I would hear him play on the radio,” he said. “When they told me he was my brother, it kind of shocked me a little. It felt good. When you got to know him, he was genuinely down to earth. We called him Balde.”

Early years

As a boy, Fender worked to help his family.

“When he was seven, he used to shine shoes in bars in San Benito,” Marla Huerta said.

On hot summer days, he‘d cool off in the resaca across the street, she said.

“He’d say, ‘I remember swimming in the resaca,’” she recalled. “He did his best to explain how it looked and how it was.”

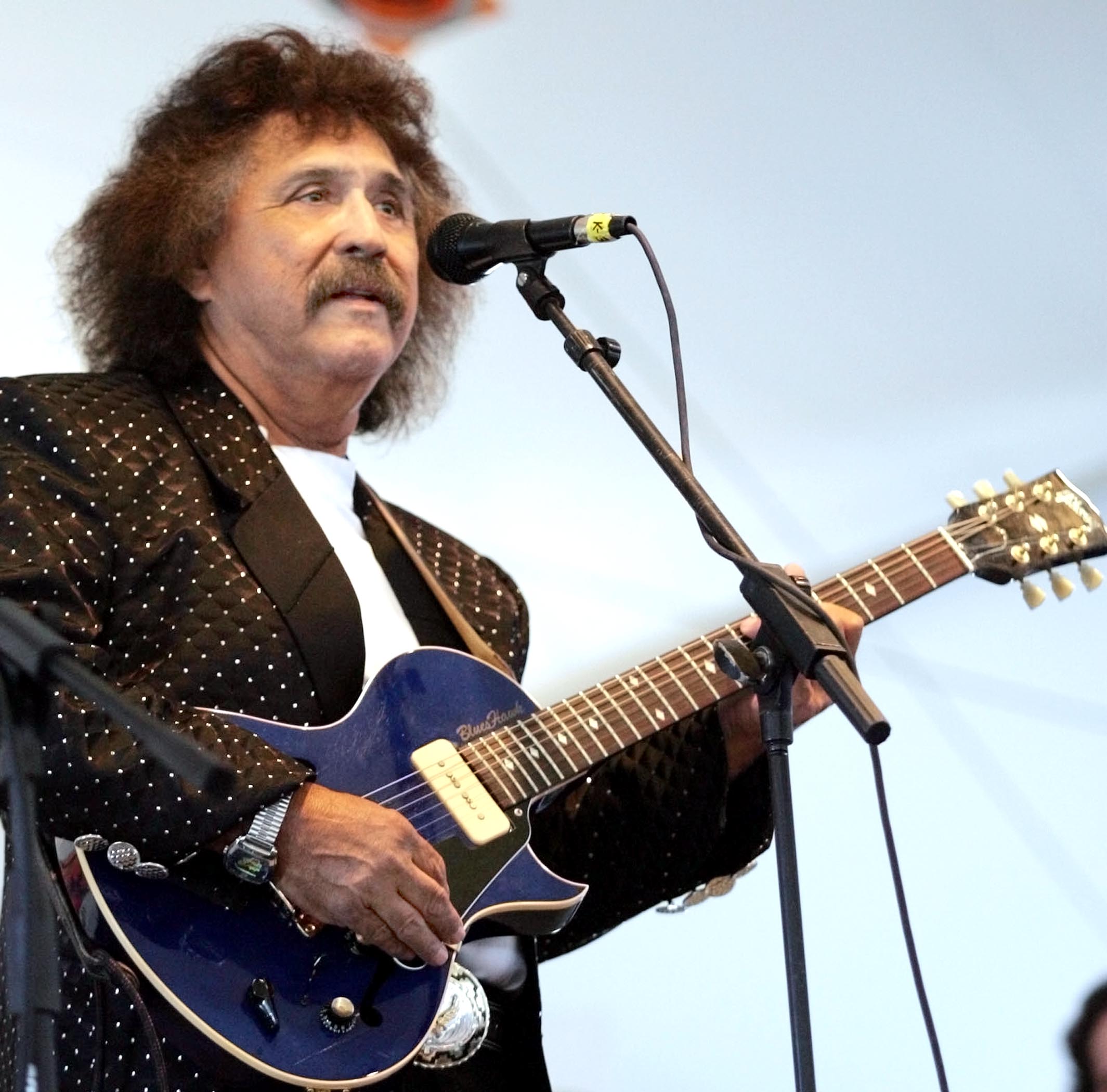

In 1959, Fender broke into rock ’n’ roll history with his rousing classic “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights.”

“It was in Harlingen where he wrote it,” Huerta said, adding he wrote the song for her mother, Evangelina. “It had to do with my mom. He wrote it for her.”

Stomping grounds

In the La Palma barrio, Mendez sparked his older brother’s love of motorcycles.

Today, his 1949 Harley Davidson stands in the Freddy Fender Museum here.

“We had this little motorcycle club here in San Benito in the barrio La Palma — about 30 of us,” Mendez recalled. “Freddy, at the time, didn’t know anything about motorcycles. He started enjoying motorcycles. After he got famous, he bought two or three of them. Sometimes when he would visit here, he’d come down on a motorcycle.”

In the late 1960s, Mendez climbed on stage to play his electric bass with his brother at Jack’s Midway bar in Harlingen.

“He came over and said, ‘Help me out,’” Mendez recalled. “We played for two hours. He gave me $10 and all the beer I could drink. It was fun.”

Years later, Mendez remembers watching his older brother wearing a San Benito High School Greyhounds’ T-shirt while playing guitar with the Grammy Award-winning super group the Texas Tornados.

“In every show he played, he would say, ‘I’m from San Benito, Texas,’” Mendez said.

Hometown hero

As newlyweds, Fender and his wife settled in the family home, Tumberlinson said.

“It’s where my dad spent a lot of time,” Huerta said, referring to the two-story brick home on Freddy Fender Lane.

“When I was younger, we’d always go there and visit,” she said. “We’d always spend hours there. The family is very important to him.”

Throughout Fender’s life, San Benito was home.

“It was his hometown,” Huerta said. “It’s where he grew up. I remember taking these drives and going to see family — my dad coming to town, driving around his old stumping grounds. You belong here. These are the people in your life. Coming to see his family was very important. You could see it in his face when he talked about it. There was a sense about being complete and bringing some peace to his soul.”