A cacophony of English, Spanish and spanglish prattle emerging from crowds threading through narrow Pulga de Alamo aisles on a sweaty Sunday afternoon in July was pierced by an enthusiastic merchant’s sales pitch, “¡A dólar! ¡A dólar la bolsa de tomate!”

Crates spilling over with Granny Smith apples, Roma tomatoes, limes, string beans, and prickly pear enticed passersby with alluring scents and cheerful bright colors.

“You come here to save,” Petra, an older woman who lives alone, said of Pulga de Alamo, an expansive flea market.

Petra hitched a ride to go to a place where she could be assured of savings. She would know. She works at H-E-B.

Petra is one of many people across the U.S. struggling with rising food costs after a pandemic, inflation and through a recession, but unlike neighbors up north, deal-seeking Valley consumers are turning to a cultural staple of the border landscape: la pulga.

Expert shoppers of the flea market are easily spotted toting large bags or pushing carts; the novice end up bearing long, red marks across their arms where heavy plastic bag straps dug into their skin during the long walk back to the parking lot.

Isabel Alvarado and her husband pulled a red canvas wagon from one produce vendor to the next.

“We bought mangos, limes, tomato, chile, nopales, calabaza,” she said, while her husband inquired about a box of mangos behind her. “Everything we use on a weekly basis.”

The dual-income family of four is unlike the historical demographic shopping at flea markets: those who struggle with food insecurity and access to food.

Alvarado is a payroll clerk and her husband has a job with industrial companies out of town.

Like many shoppers, the Alvarados noticed inflation at the grocery store. “We’ve noticed,” Isabel Alvarado said. “It’s a totally different price. We just rather come buy our vegetables and fruits here at the flea market, other than H-E-B. It’s a big difference in prices.”

By switching to the pulga, Isabel estimated they save between $20 and $40 a week.

The change in store preference for some goods represents a national trend noticed by FMI, the Food Industry Association. Their U.S. Grocery Shopper Trends of 2022 report found that concerns about food shopping have shifted from COVID-19 in 2021 to inflation and out-of-stocks this year.

Compared to the same time last year, concern with rising prices or out-of-stock food has risen; half of those polled, 53%, are now concerned with rising prices and 45% with out-of-stocks.

Of those who reported to be concerned with rising prices, 86% said they are making changes to their grocery shopping behavior like switching brands, hunting for bargains at different stores, buying less items or buying in bulk.

“When you go to a store you take three, four things and that’s it,” Petra said, referring to a traditional supermarket. “You go home because you don’t have enough money.”

Savings are more commonplace in flea markets, shoppers have noted.

“You save here, even with just the tomato bags that are sold for $2,” Viviana Flores, a teacher’s assistant with two daughters, said. Higher prices drove her to seek out savings, even if they’re minimal.

“I do my grocery shopping at H-E-B, but sometimes when I come here I take advantage of coming here and get food and veggies,” Flores said.

Flea markets boast a greater advantage over the traditional indoor grocery stores.

“Here you come to a vendor, see it for a low price, and you may not buy it,” Petra, the H-E-B employee and flea market shopper, said. “Then you go to another vendor and they sell it for less. So, you find the specials. At a store, you don’t find sales. The price is the final price.”

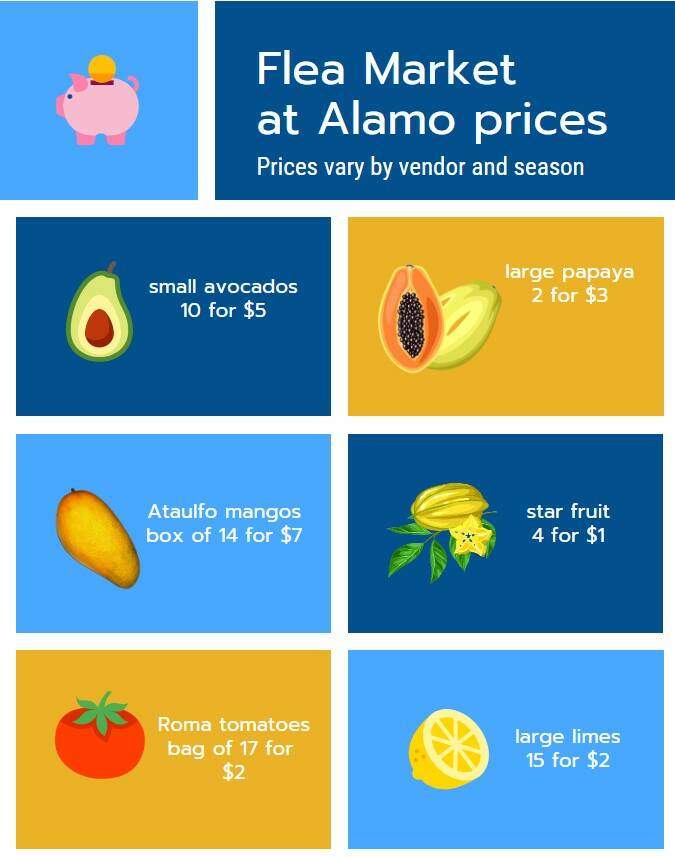

Haggling and bundles are expected and acceptable practice. That Sunday, vendors sold deals like a papaya for $2 or two for $3. Others offered discounts if more than one bag of fruits or vegetables was purchased together.

Martin Sanchez, an electrician from Weslaco, and his wife arrived with an empty cart Sunday afternoon.

The Sanchezes swiped sweat beads off their foreheads and pressed on looking for avocado, chile, tomato and jicama. “If you’re from here, you get used to the heat,” Martin said.

Sanchez’ wife asked for the price of dragon fruit. It was sold for $2.50 each, she said she had just seen that at a much higher cost in a supermarket.

A shopping experiment conducted by The Monitor that Sunday found significant savings when shopping for fruits and vegetables.

A load of groceries was purchased for $26. It contained: seven guayabas for a dollar; a bunch of bananas for $2; over 15 large limes for $2; about 17 Roma tomatoes for $2; a bag of 10 small avocados for $5; a box of 14 meaty Ataulfo mangoes for $7; four star fruits for $1; a small bag of raw tamarindo for $1; two large papayas the length of a forearm for $3; a bag of about 20 serrano peppers for $1, and a bag of four small white onions for $1.

For comparison, a similar purchase at H-E-B was about $68, as calculated through the online shopping website. Walmart’s offering excluded tamarindo and star fruit, though, even without it, the cost of the groceries amounted to $43.

The low cost can be attributed, in part, to the vendors’ preferred method of obtaining goods. Most flea market vendors, as many as 90% by the estimates of a 2011 study from the American Dietetic Association, purchase their produce from wholesalers. Even so, vendors noticed a hike in their prices, too.

“For example, the box of limes we would buy for $3. Now, it’s about $10 to $15,” Sandra Garcia, a vendor, said, as she rested her arm along the edge of a large crate of limes. She sells a bag of limes weighing two pounds for $1.

Garcia and her husband purchase their merchandise at the McAllen Produce Terminal Market, also known as Central de Abastos. Many of the imports are from Mexico.

Standards are not always the same for products that come from south of the Rio Grande, however. A downside of lower quality food can have long-lasting effects for local growers.

“If you get a grapefruit that they brought in from Mexico that doesn’t meet the sweetness standard and it’s a sourer grapefruit than we produce here. As a consumer, you’re probably not going to buy that anymore,” Dale Murden, a grower and president of Texas Citrus Mutual, said. “If a consumer gets a ‘bad taste’ in their mouth over something, they’re going to look to another product.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture changed standards for Mexican grapefruit in 2021. A study by the Texas Cooperative Inspection Program tested 208 loads of grapefruit containing 545 lots between September 2021 and March 2022. They found that if the standards had not changed, 76% of the tested lots would have been rejected.

“That’s why we try to uphold the standard,” Murden said. “They might have bought cheaper fruit, but then, you, the consumer, decided, ‘that was the worst thing I ever tasted. I’m just not going to buy that category again.’ That hurts me for life.”

Other drawbacks to shopping at pulgas are the notable absence of dairy products and eggs, a lack of nutritional labels, and the temptation to buy fatty yet savory prepared food like the iconic espiropapa.

“The rational spender is probably thinking about their immediate pocket and not the long-term consequences of eating unhealthily,” Amie Bostic said. Bostic is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Texas Rio Grande Valley who studies the relationship between poverty and social policies.

“Oftentimes, cheaper food is not the healthiest food. But what’s so neat about pulgas is they have fresh fruits and vegetables that can counter other not-so healthy options,” Bostic said.

Pulgas are integral to Hispanic communities along the border where they are reminiscent of Mexican open-air markets that invite a feeling of familiarity and promote the culture.

Flea markets are a common-sense option in a community experiencing almost double the national unemployment and poverty rate while facing a national 9% inflation rate, the largest increase since 1981, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“Another study found that among people who live in colonias,” Bostic said, adding, “the use of pulgas for fruits and vegetables led to greater food security. That’s not surprising in a sense, because if you’re buying your groceries at H-E-B as a less income secure person, you’re probably not going to buy as much. Whereas if you go to the pulga, you can buy quite a bit more.”

A 2010 study published in the International Journal for Equity in Health found fruits and vegetables were the most purchased item at flea markets.

“Having these as alternative food sources instead of just grocery stores or food markets has been a real big advantage for helping people manage the low-incomes that we have here,” Bostic said.

Over in Alamo, a large metal roof provided shade for the wooden picnic tables filled with people taking a break from the heat and listening to a Tejano band, unintentionally reaffirming the pulga’s role in the Rio Grande Valley’s foodscape.

“There’s places where there’s AC inside already. It’s getting better and better,” Viviana Flores, the teacher assistant with two girls, said, referring to enclosed spaces at the flea market like a hair salon with two barber chairs. “It’s not like it used to be. In the long run it’s going to be big competition for other stores.”