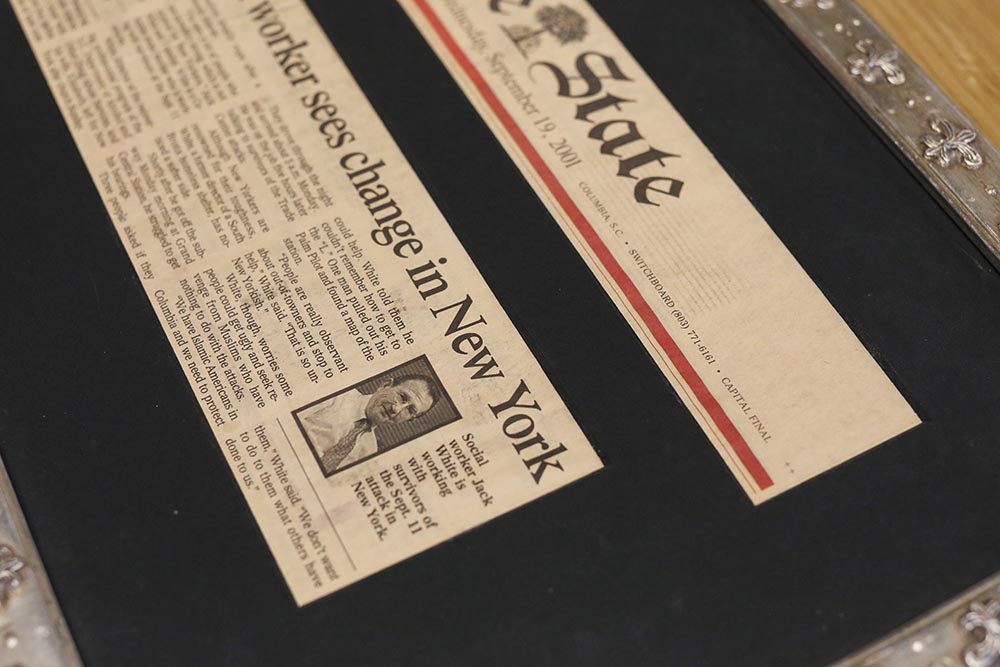

Twenty years after the attack, Brownsville residents Jack White and his wife Elizabeth Becker remember what it was like to be a volunteer following 9/11 in New York City.

White and Becker, both retired social workers, were at the peak of their careers in social work in Columbia, South Carolina, in 2001 when they were called as volunteers to work with the survivors of the terrorist attacks.

White remembers that he was working in the South Carolina Recovering Professional Program for physicians and other licensed medical professions to address addiction when on early Tuesday, Sep. 11, 2001, he arrived at his office and found all the staff gathered around computers and watching news coverage of the planes crash into the World Trade Center.

A few days later, he got a call from Washington, D.C., asking him and his wife to go to New York City to help the survivors with counseling.

“No planes were available,” he said. “So, we packed, made provisions for our dogs and cats and left for New York City. … Next morning, we received orientation on management of the crisis process with 50 other social workers and mental health workers.”

White was no stranger to helping in New York City. Prior to 9/11, he had worked there with a large homeless program called HELP, which was led by Andrew Cuomo, now the former governor of New York. White worked at the Manhattan office a block away from the Empire State Building and blocks away from the World Trade Center.

White said Becker and he worked together in rotating groups of 10 to 20 per session for about two hours each. The model allowed for the participants to tell their stories, connect with others having similar experiences, identifying strengths and resilience, he said.

“Stories included experiences of victims trying to get down crowded stairways filled with smoke, people falling and being left,” he said. “As the mass moved on, observing acts of heroism where some put their lives in danger to save others. Experiences of people jumping out of windows to their deaths, the feeling of suffocation from smoke and flame.”

Becker and he worked for about 10 to 15 hours a day for two weeks. Their routine was to work, get back to the hotel, debrief, deal with their own grief, sleep and get ready for the next day.

“I know we were a great team,” he said.

Becker said one of the things that she remembers the most is how quiet the city had become. Becker and White remember when they arrived in New York City, there was still smoke close to Ground Zero even though a few days had passed. They remember New Yorkers being extremely helpful to everyone, showing kindness everywhere.

“There was no sound. You know how loud it always is with the trucks, cars, horns, the talking, there was nothing,” Becker said. “The whole city stopped. Nobody ever believed that anything like that would happen in the United States. We were never vulnerable. That United States citizens could be vulnerable like that? There was no such thing. Everybody had to think differently.”