MATAMOROS — As the U.S. begins taking asylum cases through its new app, the government is simultaneously discovering and fixing problems.

That’s because glitches, language barriers and its design are disproportionately affecting those waiting on the border the longest.

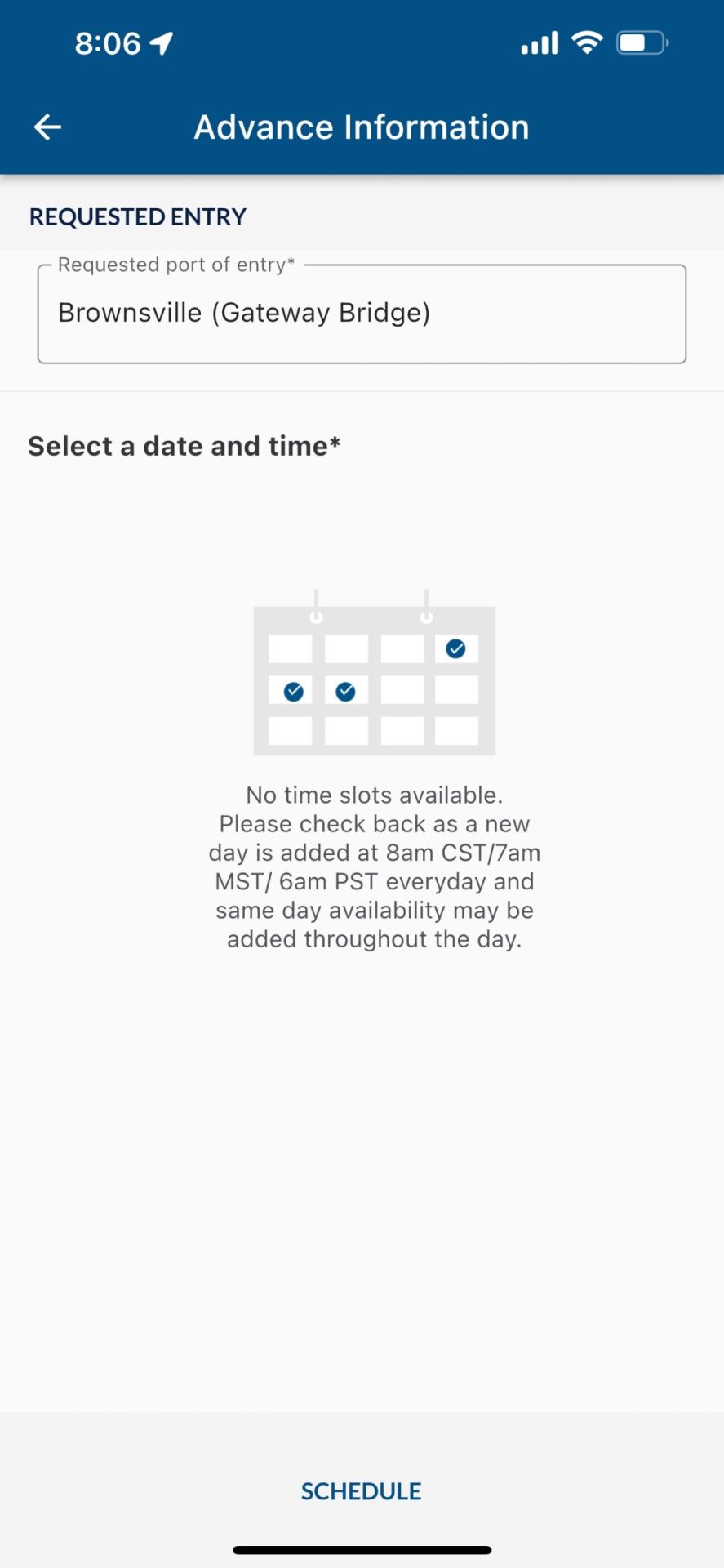

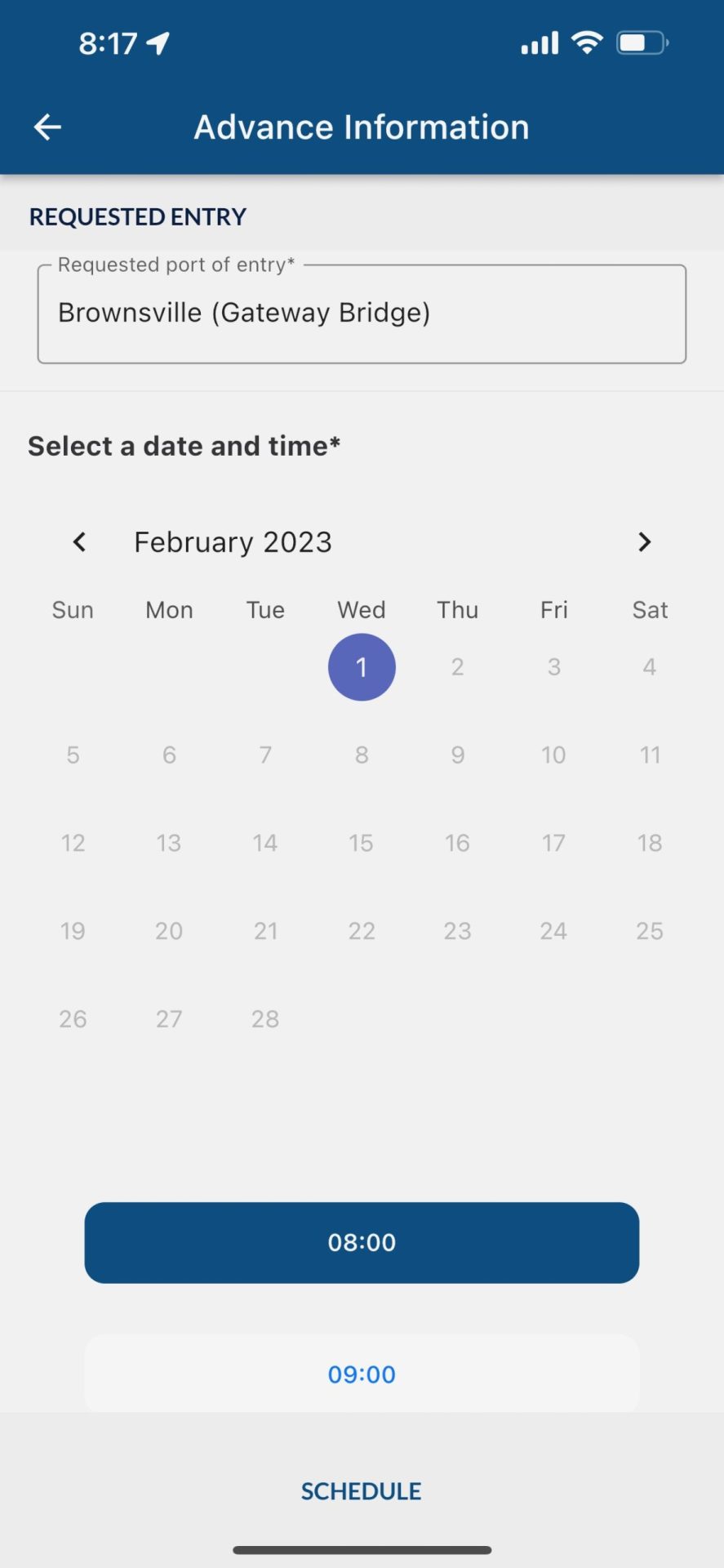

Early on a cool Friday morning, over 150 people lined up along the pedestrian walkway of the Gateway International Bridge between Brownsville and Matamoros for their 7 a.m. appointment scheduled over the CBP One app, software designed by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Bags stuffed with clothes and stuffed animals, manila folders protecting records and suitcases sat by the side of men, couples and families waiting their turn to make their case for asylum in the U.S.

“I feel happy,” Jaer, a 29-year-old Venezuelan man who stood at the front of the line, said. He withheld his last name for safety reasons in case he is sent back to his country. “I’m grateful, because it’s what we were waiting for. And by what I’ve seen, the process has been fast. I thank God that we’re already here.”

Jaer used the CBP One app the first day it opened, Jan. 12, and reported no problems accessing the multi-step system that allowed him to book an appointment at the port of entry closest to him that was participating in the program.

“I was waiting for my process, because it’s better to go in legally,” Jaer added.

The app was created in response to the rise in the number of people encountered entering the U.S. border seeking asylum only to be returned to Mexico under a pandemic-induced public health authority known as Title 42.

Some people were allowed to go into the country through a process that would exempt them from the authority of Title 42, but it relied on third parties, some which were subject to corruption, and created an obstacle between the applicant and process.

In some instances, asylum seekers were charged thousands of dollars by third parties when the process was free to sign up.

The purpose of the app was to provide immigrants a safer, more orderly and efficient process that would cut out third parties and reduce long lines that formed through the old method, a CBP official speaking on background said Friday.

Omaira Rosales, 43, dressed in a warm sweater stood close to Ali Delgado, 51, a Venezuelan man she met in Matamoros. She had a cheerful disposition as she waited on the bridge to be called for her appointment.

“I think this was a great program,” Rosales said of the process. She only faced a speed-bump with the portion of the app that requires the applicant to take a photo of themselves that is then analyzed and compared with another photo through facial-recognition technology.

Delgado said that while they did not struggle with the app, others did.

“Right now it’s a bit harder to use the app. It’s taking a while to get your code. Then you have to go back in the app with the code,” he said.

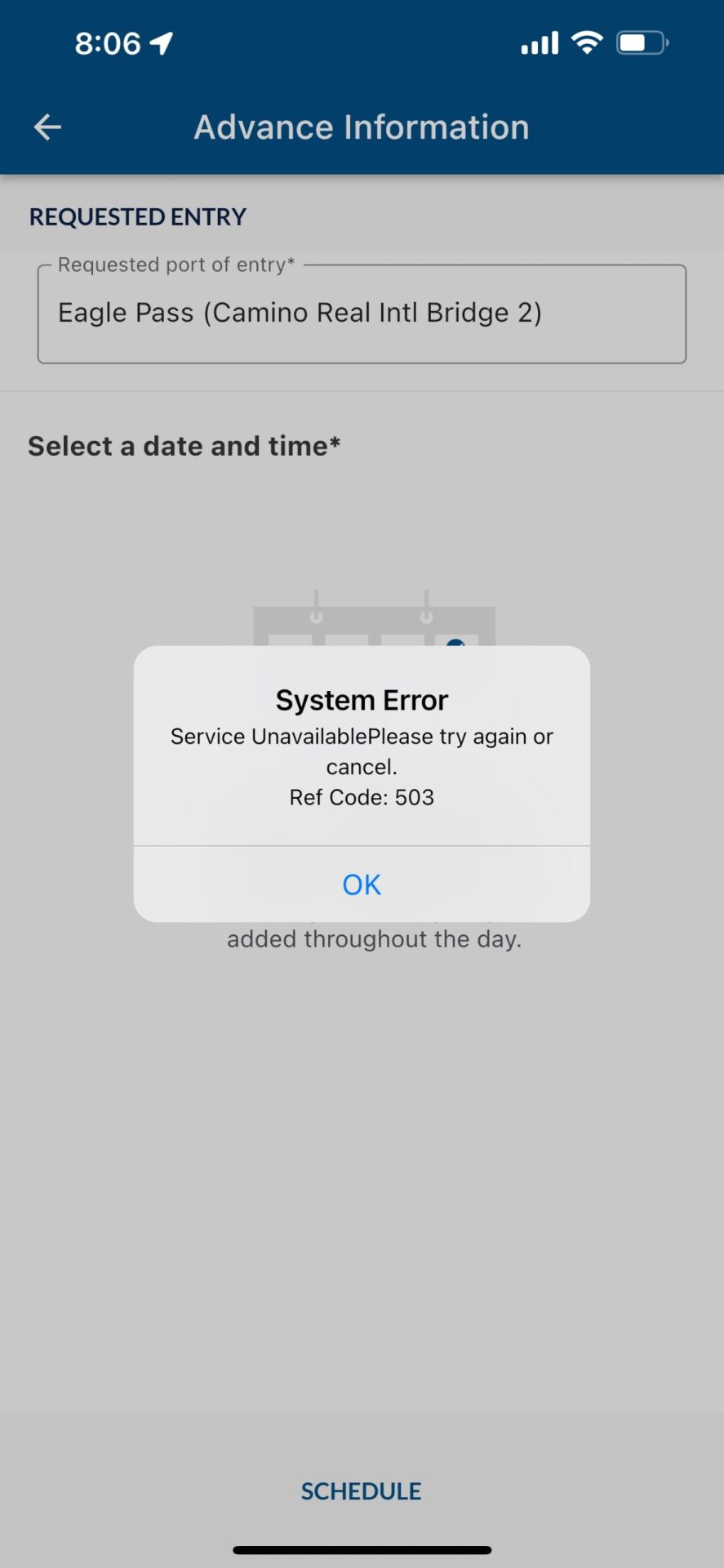

That Friday morning, the app stopped working due to an outage, a CBP official explained, a problem often prompted by a large surge in web traffic. Every morning, the servers receive thousands of requests from people like Antonio, 37, and his friend standing next to him in line, both from Haiti.

Haitians began arriving at the border for over a year to seek asylum. Many have waited for months for an opportunity to enter.

Antonio speaks Spanish, but a great portion of those along the border only speak Haitian Creole.

The CBP One app, which is only available in English and Spanish for those seeking an exception to Title 42, proved challenging for Haitians like Antonio.

“I came to accompany him, but then I’ll go back,” Antonio said, referring to his Haitian friend who spoke limited Spanish.

In the line that morning, out of about 150 people, only ten were Haitians, not including Antonio who did not have an appointment.

“I forgot to do my own application because I was helping everyone else,” Antonio said. He said he’s been using his Spanish-speaking skills to help others who can’t navigate the app due to the language barrier.

Older and those of lesser means face other technological problems with outdated phones, poor internet connectivity, broken phones and technological illiteracy, Antonio said.

“Since this started … the number of Haitian asylum seekers that have crossed in both cities has dropped dramatically,” Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, co-founder of the Sidewalk School helping immigrants in Tamaulipas, said. “It is a dramatic, noticeable drop.”

Her organization was helping immigrants sign up for the exception process prior to the use of the app and saw a greater percentage of Haitians crossing into the U.S.

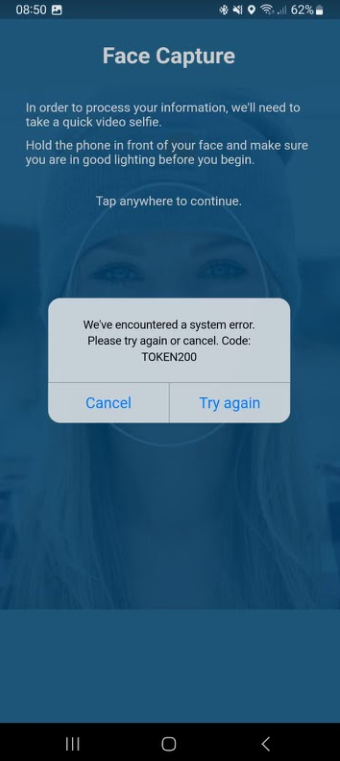

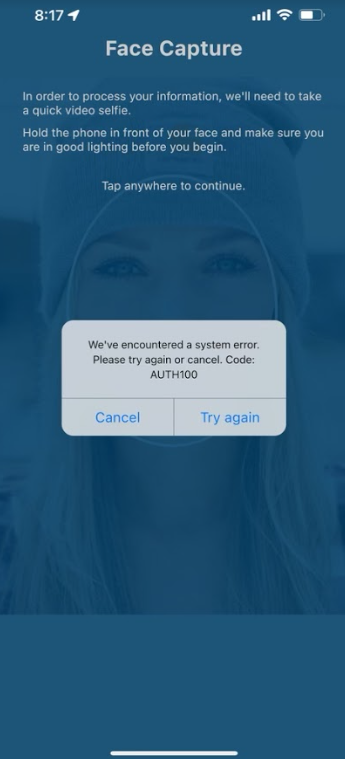

But since the app started, Haitians in Tamaulipas have experienced notable problems with the step that requires them to use their phone’s camera.

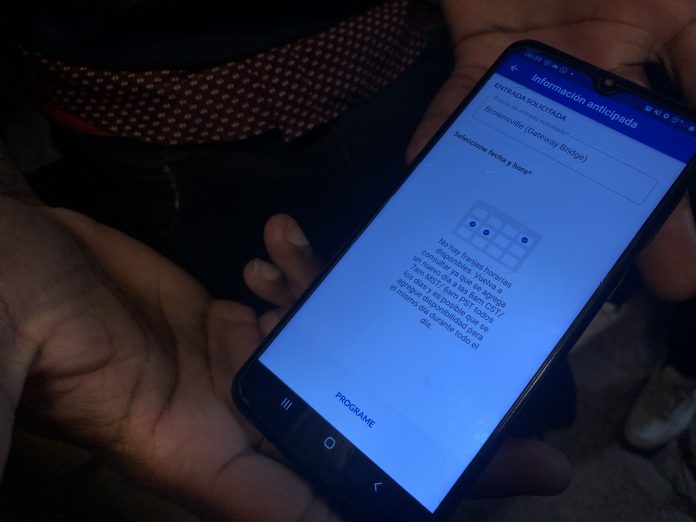

Out of 100 people who sat and tried to get an appointment Friday at a shelter in Reynosa, only one person managed to get an appointment.

Rangel-Samponaro said a common hindrance in the process is the photo they’re required to take.

“They are having many issues taking pictures of themselves and it being accepted in the app,” Rangel-Samponaro explained. “They have to have their phone brightness on max. They’re having other people hold lights to their face. It has to be a sunny day outside.”

Rangel-Samponaro fears the app is not capturing darker complected faces compared to lighter skin tones, and she’s installed lights in the shelter to help address the problem.

CBP officials who spoke on background with The Monitor said they are aware of both problems affecting Haitian asylum seekers — the language barrier and the facial recognition process.

Part of the problem is due to a confusion between two programs that are available for immigrants from Haiti.

A week ago, President Joe Biden announced two programs available through the app. One program was the exception process and the other is a program known as the Advance Travel Authorization, or ATA, that was recently expanded to cover immigrants from Haiti, Nicaragua and Cuba, in addition to the previously announced Venezuelans in October.

The ATA program requires a sponsor in the U.S. and greater access to financial resources, critics have said.

But CBP officials who spoke on background said they believed most Haitians would use the CBP One app to register for the ATA program, which will allow up to 30,000 people into the country a month.

The ATA process on the CBP One app is currently available in French, close to Haitian Creole which is a French-based language.

CBP officials said they did not anticipate high interest from Haitians in the exception program since they believed it would be easier to utilize the ATA route. However, they said they’ve seen the need and are working on adding a language accessible for Haitians in the future.

The other problems experienced with the photos may be on the user’s end, CBP officials said.

The step requiring a photo is not a typical picture. It requires the user to hold the camera focused on their face while a scanner conducts spatial comparison to detect facial features.

The technology used is comparable to that used for facial comparison by the iPhone, according to CBP officials who explained they suspect it’s a problem with the hardware used, not their software. They also said lighting may greatly affect the spatial comparison process, as well as the megapixels within the phone’s camera.

The app is a work in progress, and some who experienced problems previously already benefited from the improvements CBP made after becoming aware of the users’ experiences.

Deiberson Villalobos, 17, and his father, Deinys, 39, both from Venezuela, were nearly split up at the border by a glitch in the app that didn’t allow for families to schedule appointments together. The government fixed it and they were both at the bridge on Friday.

Deiberson, the son, said he felt “blessed” to be at Gateway International Bridge with his dad.

“Thank God, it was worth waiting and respecting the laws of the U.S.,” his father said.

Some immigrants who signed up did not find appointments at the Brownsville port of entry but found slots available in other parts of the border were left to figure out transportation.

“Already families have been kidnapped going from Matamoros to Piedras Negras; more than two families,” Rangel-Samponaro said.

That risk is compounded by federal laws that outlaw the transportation of immigrants illegally present in Mexico.

CBP officials said they are aware of the issue but the applicant is ultimately allowed to choose their appointment location.

Other problems with the location are more insidious.

Of the crowd present at Gateway International Bridge on Friday, only three people were Russians. They said they did not encounter problems with the app, only the language barrier.

Prior to the process changing, dozens of Russians were crossing.

Tatiana, a Russian mother, who flew to Mexico with her daughter and married a U.S. citizen, Josh, in Cancun, were hoping to cross quickly.

Instead, Tatiana and her daughter have been stuck in Matamoros for two weeks now with no luck signing up on the app.

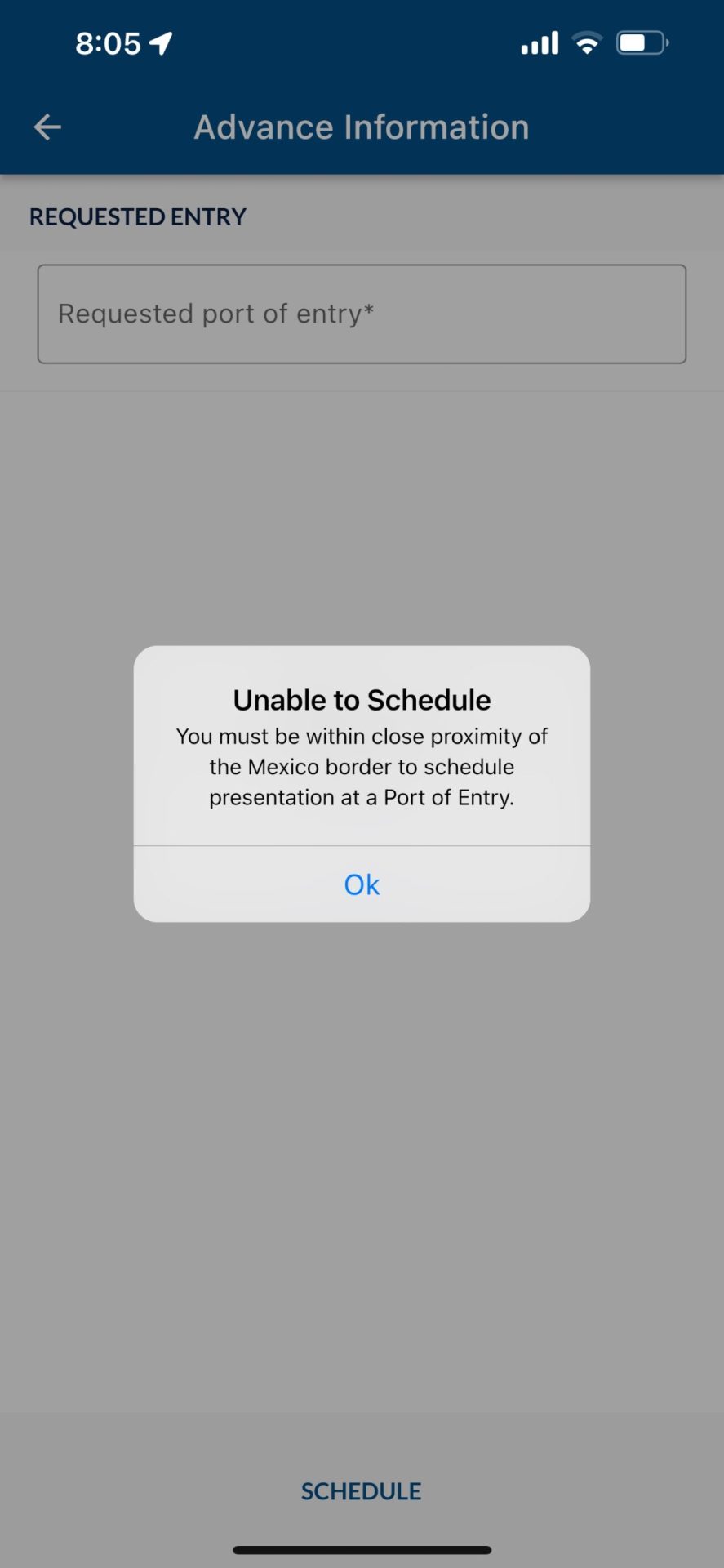

They’ve been staying at a hotel in Tamaulipas but have been kicked out of the app’s process or stalled midway multiple times. On one occasion, the app said they were not close enough to the border to be eligible to register.

As part of the exception process, immigrants must be in a border city to be able to sign up. Geofencing technology aids in enforcing the process, but it’s proven unreliable for some users whose signal may bounce off of antennas around the border, CBP officials said.

The unanticipated use of VPNs, or Virtual Private Networks, also allowed some users to circumvent the geofencing, CBP officials added, a problem they’re also working to resolve.

Tatiana estimated there are about 700 Russian families in Matamoros who are hoping the app works for them soon, before their money runs out.

Her husband, Josh, said he’s trying the app at all times of the day hoping to catch a good signal and an open slot.

So far, they only see a screen telling them to try the next day.

CBP officials said they’ve had to allocate more servers to the app to amplify their capacity.

Josh and his wife said they’re concerned about safety as their time in the border city stretches out with no end in sight.

Antonio, the Haitian man who had to leave his friend at the bridge and return to Matamoros, said he’s holding out hope on this process.

“We have to keep trying because we want to cross,” Antonio said. “We have that program to cross legally … we don’t want to cross illegally.”