For the people who knew him, it was hard to distinguish Rene Sandoval Sr. from his music.

Sandoval was, they say, an elite musician who mastered jazz and the saxophone and a variety of other instruments and genres; he was also a consummate gentleman, a hard-working family man and a devoted friend with a magnetic personality.

Sandoval, who died Saturday, Jan. 29, at the age of 86, deeply impacted the lives of virtually everyone who knew him with a force of character you could hear in his music.

When friends and family describe how Sandoval wailed on that saxophone, it’s almost like they could hear all of that love and passion and professionalism pouring out of the instrument’s brass bell.

That music could make his family cry, thinking about the role model he set as a father. It would make friends smile, remembering old jokes and pranks from practices, and it’s the kind of music that makes old bandmates cherish amateur recordings from live shows taped years ago.

It was the kind of music that made a lasting imprint on a fledgling Texas jazz scene half a century ago, and that inspired other artists to take up instruments of their own.

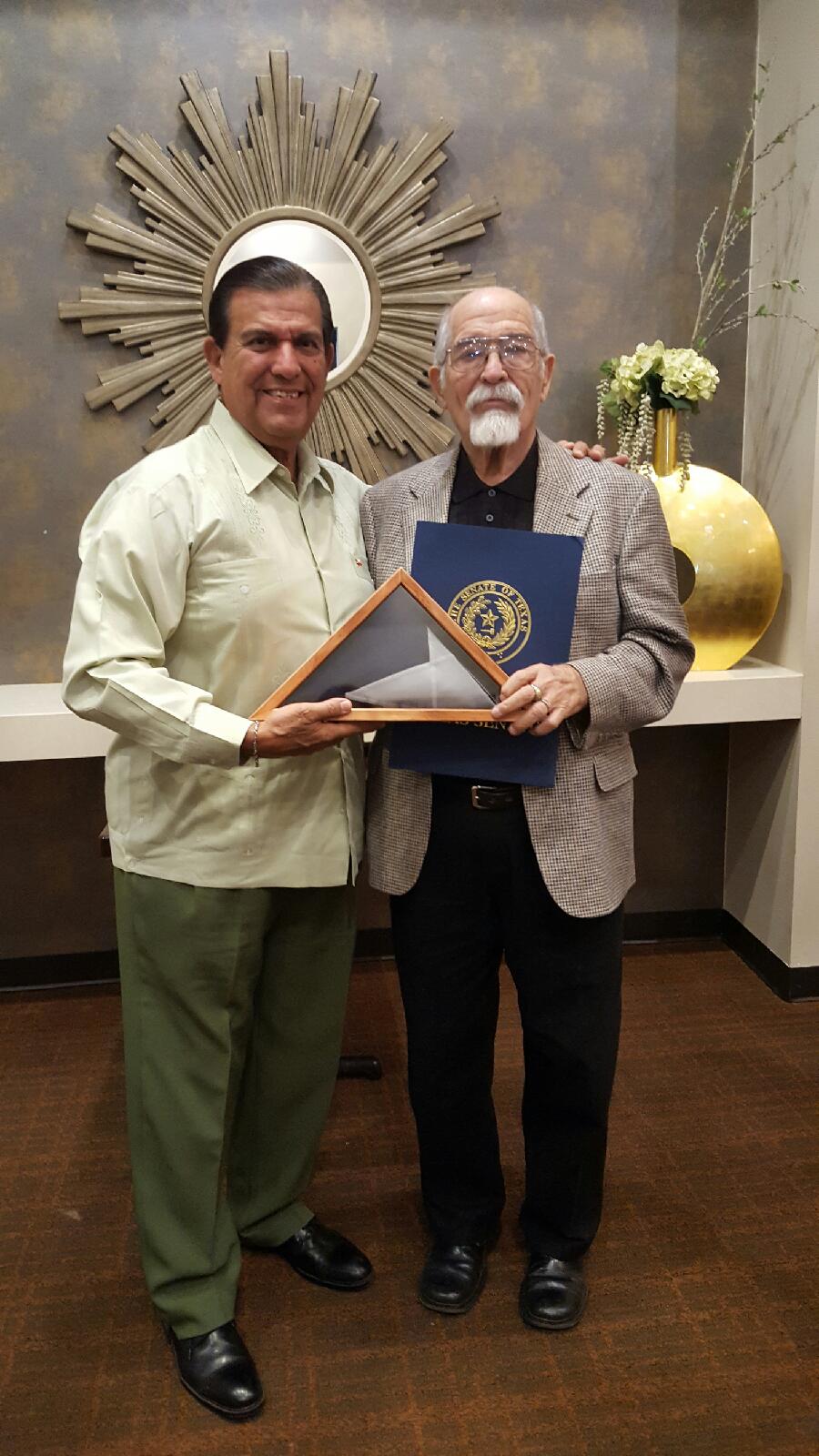

“He was a great talent to begin with, he was a great musician,” said Tejano musician Little Joe, who often sat in on Sandoval’s performances and became a close friend. “But he was also just a kind person. Always in a nice, positive mood. We’re all gonna miss him.”

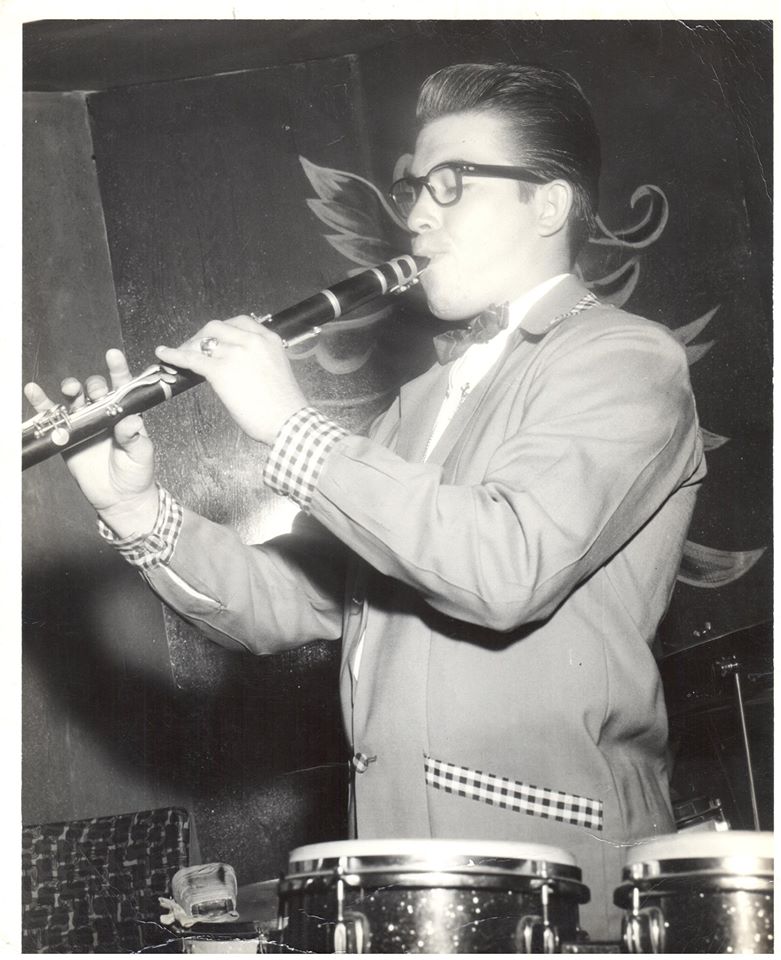

A Pharr native, Sandoval learned to love music through his mother. She taught him piano, and he picked up the clarinet in grade school. He turned out to be something of a prodigy, joining PSJA High School’s band as a seventh grader and starting to play saxophone professionally at dance halls at the age of 13.

Sandoval would spend the rest of his life playing and singing, in a dizzying number of venues and bands and genres. He would play blues and Tejano and jazz, playing with anybody and playing for anybody, outliving dozens of the clubs and groups he performed in.

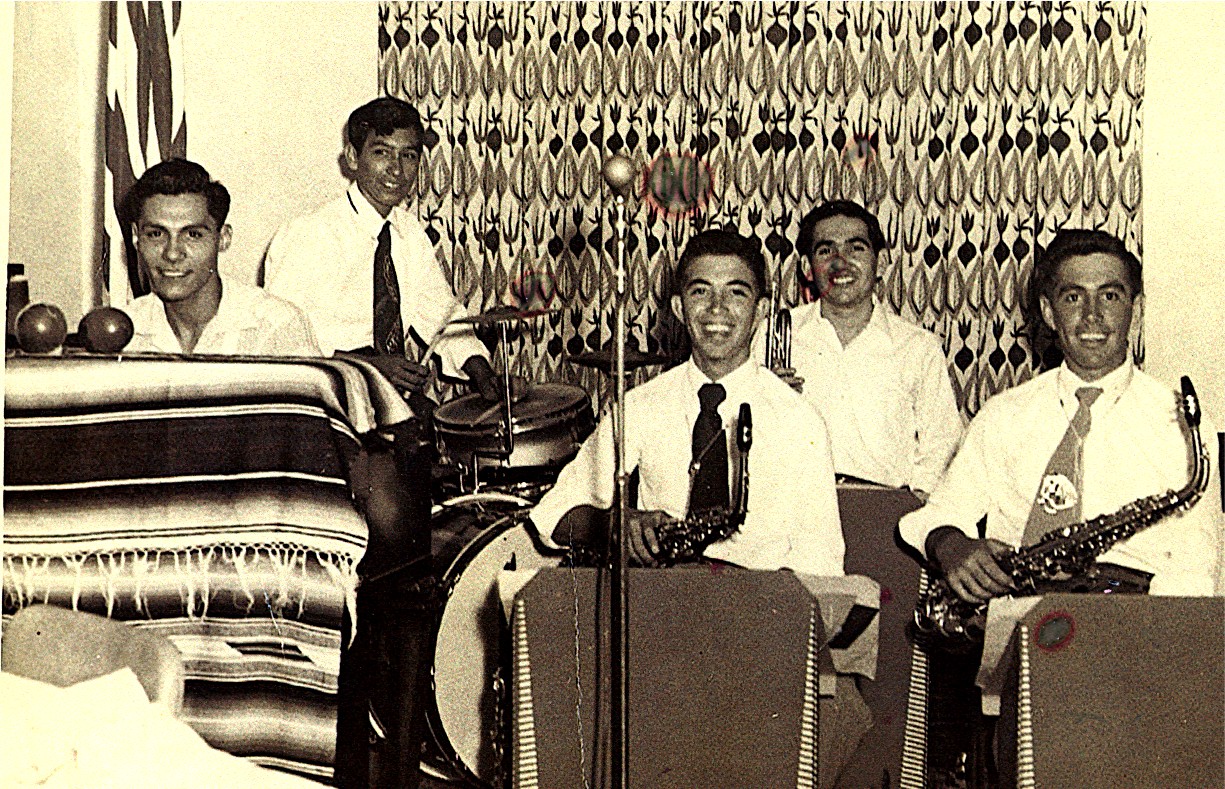

Toward the start of his career, in the mid-50s Sandoval fronted an eight-piece big band playing for a local TV program called Fiesta Latina, playing ballroom staples and nascent Tejano music.

Sandoval was in his late teens, lanky and boyishly handsome, noticeably younger than the rest of his bandmates.

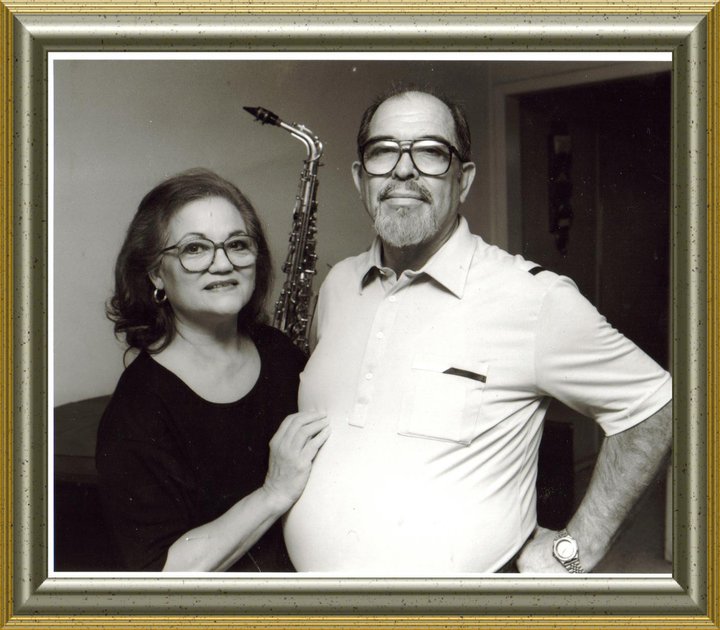

Minerva Rodriguez, the band’s singer, was in her early 20s. A slender woman with a heart-shaped face framed by a coif of black curls, she’d sing in satin gowns and heels and hoop earrings, looking like she’d just walked out of Hollywood.

“They just fell in love, playing music together,” Patty Sralla, Sandoval’s daughter, said.

Rene and Minerva eloped and moved to Houston. Sandoval found work quick, spending his evenings playing at a nightclub till the wee hours of the morning and working as a train mechanic in the daytime.

That part, staying busy, would never really change for Sandoval. He’d go through most of his life balancing his musical career with day jobs, often in radio or government programs, always carving out time to spend with an ever-growing family.

“He would wake up and he’d ask my mom, ‘Am I going to the day job or the night job?’” Sralla chuckled. “He’d have to ask her, because he’d work all the time.”

The schedule didn’t hurt Sandoval’s music. He found success pursuing Latin-style jazz in Houston through the late 50s and 60s, playing at some of the hottest clubs in town with a variety of bands.

It wasn’t uncommon for celebrities to drop in at the clubs Sandoval played, people like Burt Reynolds and Liza Minnelli and Betty Grable.

Sandoval joined The Jokers, who opened for artists like Glen Campbell and The Byrds, and he performed a stint at The Bastille Club, sharing the stage with jazz idols like Cannonball Adderly, Dizzy Gillespie and Louis Hayes.

That was the highpoint of Sandoval’s Houston days. He could play different kinds of music, but jazz was always his passion, and he did his part teaching Texas to love it just as much as he did.

In 1961, Sandoval helped found the Texas Jazz Festival in Corpus Christi, fronting his very own band. He attended all but one of the subsequent festivals.

Sandoval toured nationally in the early 70s, but with his family in mind, he set down more permanent roots back in the Valley.

Bob Henry met Sandoval around that time, when the latter was searching for a drummer for the newly formed Rene Sandoval Quartet.

Henry was awed. Sandoval, he said, was a musical genius.

“I’m not talking about the best in the Valley, I’m not talking about the state,” he said. “I’m talking about this guy could walk into any nightclub in New York City, in Los Angeles, and he could keep up with the best.”

Their first gigs together were a departure from playing the Bastille Club up in Houston. The quartet started out at a little night club in a rough part of McAllen.

There were, Henry said, shootings, stabbings and fights, more than one of which proved fatal. Nobody ever messed with the musicians, Henry said, and the occasional drug kingpin would drop in to listen and buy the band a round of drinks.

“I remember one night, a guy got shot in the bathroom, and we were up there playing and Rene just took the mouthpiece out of his mouth just long enough to say ‘Somebody got shot,’” Henry said. “And then he went right back to playing.”

Another nightclub in town, the Papillon, offered the group a little more money to play five nights a week. Before long, the Quartet was packing the house and playing for a slightly more respectable crowd, folks who were doctors and lawyers and politicians.

“But Rene got along with everybody. I mean, whether you were a DA, you were a sheriff, whether you were a college professor or you were a gangster, Rene would sit down and talk to you like anybody else. You know, he’d sit down and have a drink with you,” Henry said.

Sandoval had an idea at the Papillon. Henry played trumpet as well as the drums, the group’s piano player could play trumpet too.

Sandoval asked them to try playing both of their instruments at once, and they could. The group would play jazz and Tejano and dixieland music, switching out instruments or playing two at once. They made the quartet sound like there were seven musicians in it.

That energy and that passion for performing never left Sandoval, said Henry, who played with the man for eight years.

“There was nobody more about his passion and about his music than Rene was,” Henry said. “After 50 years of knowing him, there wasn’t a time when I wasn’t amazed when he’d play.”

Sandoval played on Sixth Street in Austin for a stint in the early 80s, and then came back to McAllen to form the Pajaros Locos Band.

In 1987, Sandoval found what would become the most permanent stage out of the hundreds he played on in his career at the old Embassy Suites in McAllen. He and a quartet would play there Fridays and Saturdays for most of the next 30 years.

The tens of thousands of hours Sandoval spent performing will mostly only live on in memory. He never cut an album on his own and comparatively little of his music was ever recorded professionally.

“It’s unfortunate,” Little Joe said. “I don’t know why he didn’t record albums of his music, which he could have easily done.”

In a way, Sandoval left behind a legacy that’s more appropriate for a performer who was so dynamic and energetic, a legacy that lives on in the musicians he inspired and that music scene he helped create.

Joe Chapa is one of those musicians. He was a kid when he met Sandoval at one of those Corpus Christi jazz festivals back in the 90s.

Sandoval was getting ready for his show when Chapa went up to introduce himself. Without missing a beat, Sandoval told the kid to grab some gear and help out.

“When I heard him play, he was a force,” Chapa said. “For me at that point, it was eye opening. I mean, that’s what I wanted to do.”

Sandoval let Chapa sit in on gigs, and Chapa soaked up the music. Sandoval gave Chapa as much life advice as he did music advice, encouraging him to stay in school and stay away from drugs, and helped Chapa buy groceries when he was going through hard times.

Sandoval, Chapa said, laid the foundation for the man he is today.

“I’ll be forever grateful for that,” he said.

George Trevino, a retired band director and Sandoval’s nephew, was another mentee who says Sandoval made him the man he is today.

“His inspiration for many many musicians who have come from the Valley and gone on to become pretty well known is incredible,” he said. “There’s just too many to name, but there were several people who were inspired by him and the things that he did.”

Trevino said his uncle was aware of that authenticity in his music, that spirit to his playing that seemed to connect him so tangibly with whoever was listening. Trevino says Sandoval called it soul.

“Anything that he did just had a deep, inner soul to it, and it really grabbed you,” he said. “Whether it was blues or jazz bebop or latin music, whatever. They were all connected with that soulfulness.”

Visitation for Sandoval will be from 3-9 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 10, at Funeraria Del Angel, located at 3611 N. Taylor Road in Mission. Rosary recitation will be held at 7 p.m.

Funeral Mass is then scheduled for noon Friday, Feb. 11, at Holy Spirit Catholic Church, located at 2201 Martin Ave. in McAllen, with the burial set for 1 p.m. at Valley Memorial Gardens, at 3605 N. Taylor Road in Mission.

Services will also be live streamed at ww.facebook.com/FDAValleyMemorial.