Amidst the largest migrant shelter reaching capacity, a record number of migrant apprehensions, transportation shortages and a disastrous state order threatening to endanger lives and further strain resources, emails flew late July between Rio Grande Valley and D.C. Border Patrol officials who worked to mitigate each challenge as local authorities struggled to keep up.

The Monitor obtained a copy of those emails via a Freedom of Information Act request that revealed an urgent tone as solutions were running scarce.

Border Patrol’s Rio Grande Valley sector declined interview requests for this story.

JULY 26 — CHALLENGES AT EVERY TURN

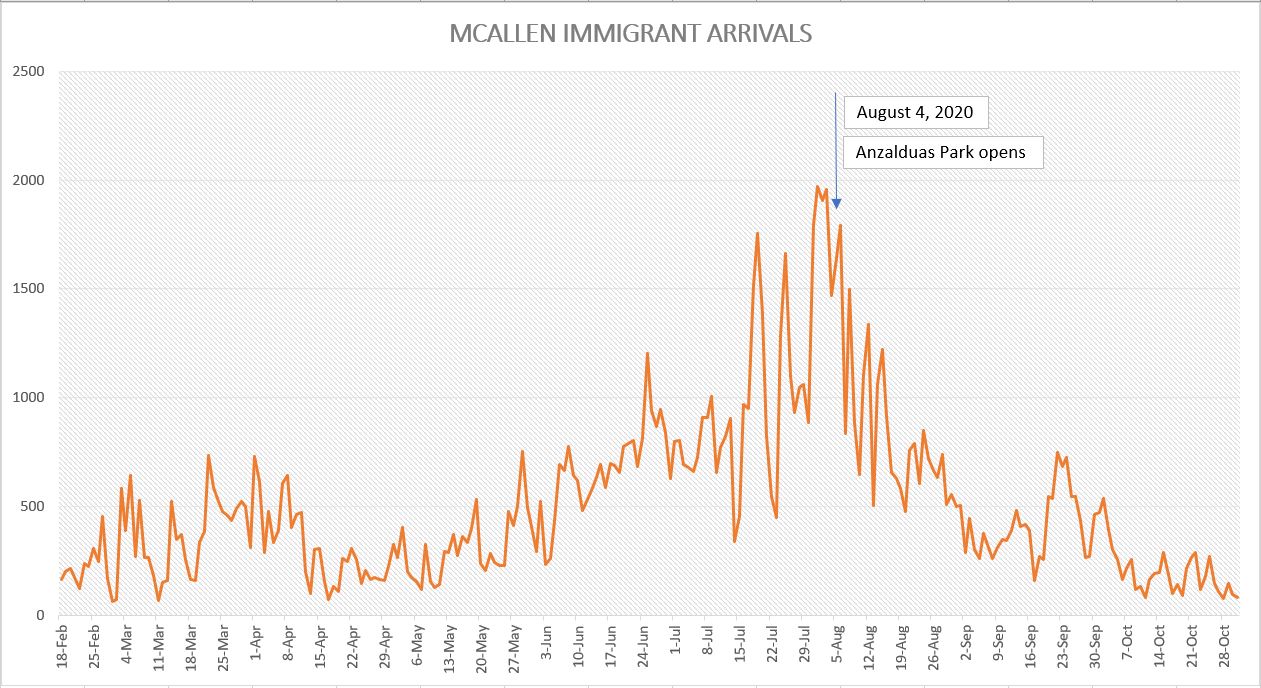

As of the end of October, the number of migrants released from federal custody in the McAllen and Mission area are dramatically lower than the peak seen in late July and early August when nearly 2,000 people were dropped off by Border Patrol. This paralyzed operations at the Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley’s Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen on July 26.

Border Patrol agents were aware of the tipping point before it happened.

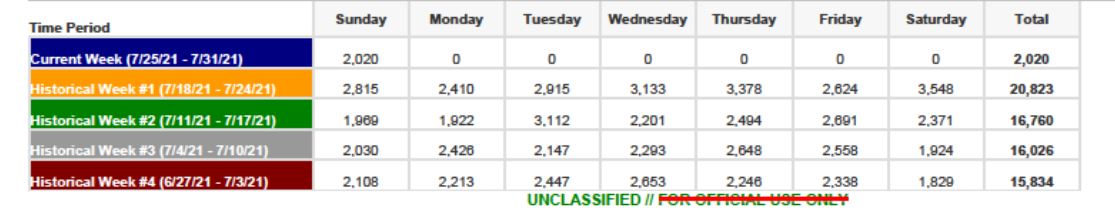

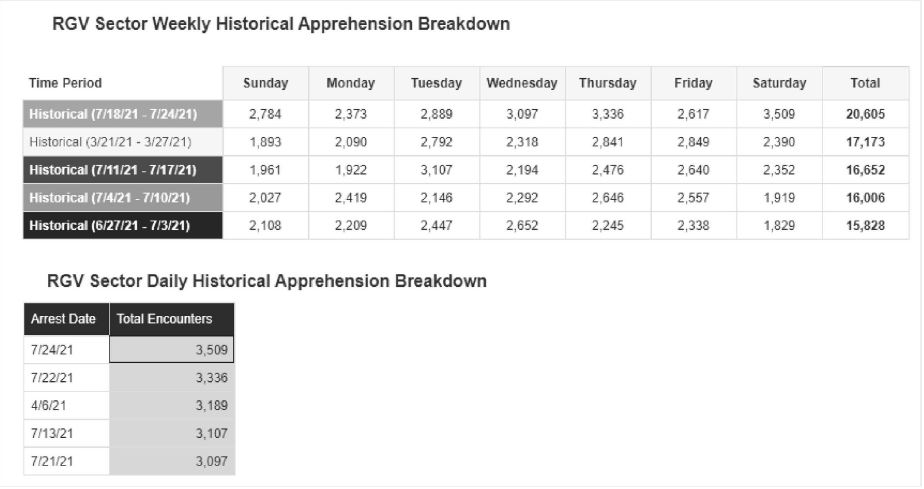

That same morning emails began circulating at 6:56 a.m. on July 26. After receiving a daily apprehension breakdown report, Valley sector Chief Brian Hastings requested a historical report to gauge how their apprehension numbers compared. An answer was sent back that morning proving the previous week’s total number of apprehensions, 20,823, was the highest in the sector’s history.

>> Historical week no. 1: July 18-24 — 20,823

>> Historical week no. 2: July 11-17 — 16,760

>> Historical week no. 3: July 4-10 — 16,026

>> Historical week no. 4: June 27-July 3 — 15,834

Their daily historical apprehensions were also the highest they had ever been. All top five happened this year with four of them happening that same month.

>> July 24 — 3,509

>> July 22 — 3,336

>> April 6 — 3,189

>> July 13 — 3,107

>> July 21 — 3,097

Meanwhile, other emails were sent that morning addressing a growing crisis within their processing of migrant children.

On Monday, July 26, at 8:48 a.m., an email was sent to Chief Hastings from D.C. stating, “Can you do me a favor and reiterate that UCs must get prioritization in the processing? Any help would be much appreciated. This issue is reaching the top level of the Administration again.”

A response was sent back nine minutes later stating “UC numbers are ugly,” referring to unaccompanied children which were at 1,420 in total custody at that point. Only 403 of them were processed with 1,017 in queue.

The Central Processing Center, or tents in Donna, were already focusing on that, and they were expecting more processors back since “OFO started today,” meaning CBP’s Office of Field Operations.

Border Patrol considered increasing the number of their agents assigned to processing duties by leaving checkpoints unmanned temporarily, a decision that was not approved by headquarters in D.C.

That afternoon, Hastings said they were working hard to “right size processed numbers.”

Four days later, on July 29, Hastings wrote to Chief of Law Enforcement Operations at CBP Manuel Padilla to explain the problem in processing unaccompanied children involved the Office of Refugee Resettlement, ORR.

Although the Valley sector was processing unaccompanied children according to their length of time in custody and giving priority to children with special needs, “Our issues right now is that ORR is not prioritizing placement by TIC,” or time in custody, Hastings wrote.

“ORR is taking UACs [unaccompanied children] that are easier to place based upon age and gender and taking longer to place certain age groups that are harder to place (older UACs and preg UACs).”

Hastings informed Padilla they had made progress in the last four days.

“The team is prioritizing UACs and every processing computer is occupied again today,” he wrote.

The afternoon did not bring better news.

A flurry of emails sent after 1 p.m. describe the halt of migrant releases.

“Just got a call from [name redacted] advising Catholic Charities is not accepting any drop offs,” the email sent to Chief Hastings read. Operations at the respite center were at a standstill when they reached their maximum capacity.

“I told them to drop off at the bus station for this load,” another email from a redacted account responded a few minutes later.

Hastings informed Padilla of the situation at the respite center.

“At this point, we do not have capacity or throughput to continue holding processed FMUAs (families). We intend to drop off processed FMUAs at the McAllen Bus station,” Hastings wrote. “We are informing McAllen city leadership and local PD’s now that we intend to drop off at the McAllen Bus Station.”

An hour later, Hastings told Padilla the city would be providing testing at the drop-off site.

Agents were simultaneously looking at options that would decrease the number of people in their custody, including starting up the ENV program.

ENV processing refers to the Electronic Nationality Verification Program which enables the fast removal of certain Central American migrants, as explained by the American Immigration Council.

That evening, a short email was sent from Padilla to Hastings at 7:50 p.m. simply titled, “Help.”

Padilla informed Hastings they were sending some help in the form of an agent experienced in ENV processing who was “knee deep into the surge in FY19.” Under this program, migrants would be flown back to their home countries, but unexpected COVID-19 test results lay ahead days later that would significantly hamper their efforts.

JULY 27 — TRANSPORTATION PROBLEMS

Transportation for the large number of migrants was running scarce in the Valley but it was also straining current vehicles in their fleet.

In a series of emails that range from July 23 to 28, emails labeled “high” importance stress the need for more resources.

A trail of emails shows Hastings’ request in the Valley grew from six vans and 12 drivers (July 23, 6 p.m.) to 10 buses and eight vans in five days. In between that time, a bus carrying migrants caught fire.

Hastings informed Padilla on July 27 that a contracted ISS bus carrying over 60 detainees caught fire on the freeway in McAllen.

The city’s police and fire department responded, along with Border Patrol agents. The driver evacuated the detainees.

“It does not appear to be a serious fire and there are no known injuries at this time,” Hastings wrote.

The next day, a solution to their transportation woes would be even further out of reach.

JULY 28 — ABBOTT’S EXECUTIVE ORDER

The Texas Department of Public Safety reached out to Hastings on July 28 to inform him that the governor would be restricting migrant transport through an executive order signed that morning.

Hastings sent an email to Padilla and Border Patrol sector chiefs in Laredo and El Paso at 5:02 p.m.

The executive order would have “a specific focus on…those traveling to and from the Respite Centers,” the email stated.

DPS even planned to station a trooper outside the respite center, where over 1,000 migrants were being dropped off daily at the time, according to an amicus brief filed a few days later.

Hastings realized the executive order could lead to serious “harm,” as he stated in an affidavit later filed in a federal court.

“CBP would be faced with untenable choices such as continuing operations with increased numbers of migrants in their facilities or have CBP law-enforcement officials transport these migrants,” Hastings wrote, stressing the logistical strain.

Medical concerns were also raised since ambulance drivers, who are not law enforcement officers, would not be allowed to drive migrants to hospitals under the executive order.

Sister Norma Pimentel, executive director at the respite center in McAllen, similarly predicted “catastrophic problems” if migrants were not allowed to leave the city if commercial bus drivers would be barred from driving them to their out-of-town destinations.

Though the executive order would eventually be kept from enforcement due to legal intervention, it was the source of great stress for many working to process, transport and shelter migrants at the time.

Strife and confusion was internally growing after the “help” sent to kickstart the ENV program in the Valley sector.

A deputy chief patrol agent who was previously in the Blaine sector and considered an expert on the program referenced in a July 26 email, had experience in “managing a CPC [central processing center] during the 2019 crisis and literally kicking ENV back on.”

“He is not moving in and taking over,” stated a July 28 email from a deputy chief of operations addressed to Hastings. “Our hope is that he is welcomed in as part of the team, not sent in to take over.”

Hastings replied an hour later and wrote, “We welcome the team, just not a takeover of commanding the Central Processing Center.”

The agency prepared to move forward with the flights sending migrants home, but they also received notice that day of a modified policy known as Title 42 which expelled migrants back to Mexico.

“In an effort to manage current detention levels, specifically in sectors like RGV, where encounter numbers are overwhelming organic and downstream effects, USBP SWB Sectors will maximize the use of Title 42(T42) for single adults (SA) and family units (FMU),” the email stated.

The change would allow them to fly migrants to other sectors that were not overwhelmed with processing and send them back to Mexico “in alignment with local restrictions and specific criteria set by GoM (Government of Mexico).”

JULY 29 — COVID STYMIES EXPULSION FLIGHTS

On July 29, the agency would be made aware that positive COVID-19 tests would create an obstacle to the number of people they planned to fly back home through the ENV program.

“The testing of FMUA in our facility and the high number of positive results has the Loyal Source medical providers very concerned,” an email sent July 29 read. “So far, out of the 132 manifested, 26 have tested positive with nearly 60 requiring isolation.”

Hastings informed Padilla of the “very concerning ratio coming from ENV candidates.”

Padilla asked, “What will the flight look like, do you think?”

Hastings said he estimated only about 40 to 50 would still go.

Originally, 147 migrants, 12 from El Salvador, 74 from Guatemala, 61 from Honduras, were scheduled to be flown out. After testing, an email sent late at night showed only 75 were available for the flight. Testing determined 72 had the virus or were high risk family members.

Hastings also used the opportunity to let Padilla know they need more medical personnel for intake and outtake, because “they are overwhelmed and getting very worried with all the positives.”

EFFECTS IN THE VALLEY

The busiest day for agents in the Valley came a few days later when about 10,000 people were in their custody July 31 into Aug. 1.

It sparked a change in the conversation held by Valley officials like McAllen Mayor Javier Villalobos and Hidalgo County Judge Richard F. Cortez, who issued local disaster declarations on Aug. 2.

“The goal is to put us in a position that would make a claim with the federal government to the situation that we have here in Hidalgo County dealing with legal immigrants,” Cortez said, noting this declaration is the first step in possibly securing federal resources and reimbursements.

Villalobos and the commission later voted to create another drop-off site after the respite center in McAllen reached capacity, stalling the release of migrants on Aug. 3.

Since the peak of August, releases have drastically fallen into the double-digits as of late October.

Although Chief Hastings declined an interview request, he shared a statement via a news release that provided information on “all-time high” migrant apprehensions for fiscal year 2021.

Agents in the Valley encountered 549,077 migrants from October 2020 through September 2021, accounting for 33% of all Border Patrol apprehensions nationwide.

“Our agents play a critical role in border security and keeping dangerous drugs and criminals off our streets,” Chief Patrol Agent Brian Hastings stated. “I am extremely proud of our workforce for their dedication and of the collaborative efforts of our law enforcement partners in south Texas who support our frontline agents and our mission.

“When it comes to border security, our men and women in uniform perform their duties to their highest standards.”