Editor’s note: The following is a historical account of the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, compiled from The Monitor’s newspaper archives published at that time. This is the first story of a two-part series about the Rio Grande Valley’s response. The second is available here.

Exactly 79 years ago, Emma Jones openly wept while she and other members of the Rio Grande Valley Navy Mothers club bundled up 77 Christmas packages with homemade cookies and candies to send to their sons and husbands serving abroad.

Jones had founded the club about a decade earlier, inspired by her son Jimmy, who was serving at a naval air station in Panama as an aviation machinist first class. She thought it would be a good way for family members of Navy men to learn about life in the military and better understand the men they loved who served in it.

The club had taken off and Emma had become something of a national figure. Branches sprouted up around the country and she embarked on tours of both coasts with her gospel of military support, affectionately called “Aunt Emma” or “Mother Emma Jones.”

Jones wasn’t the only one crying that Monday morning. Like the rest of the nation, she had learned about the attack on Pearl Harbor the previous day.

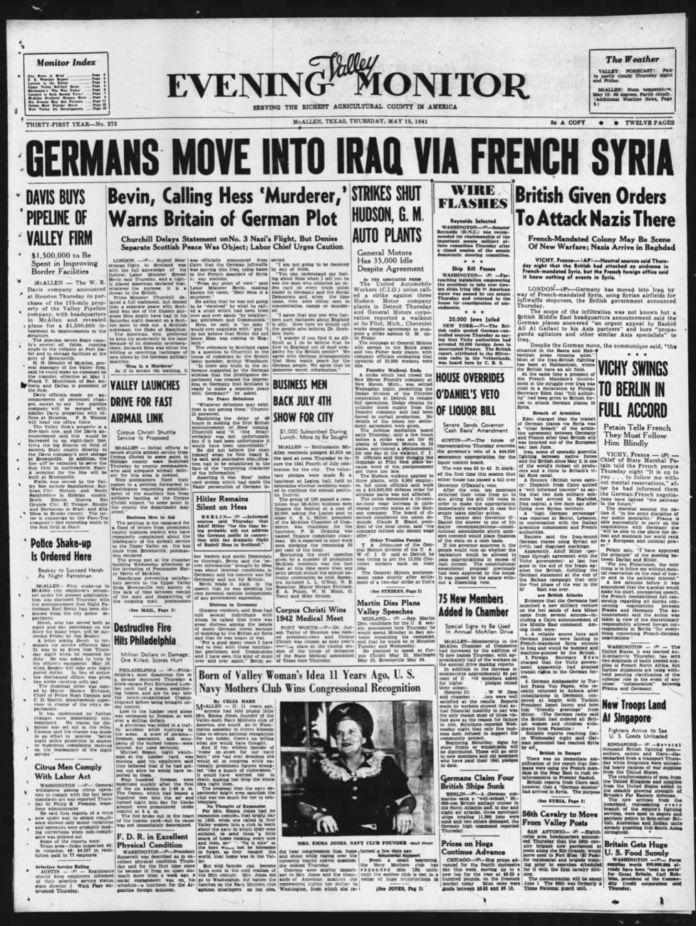

Emma Jones founded the Navy Mothers club and helped distribute information on Rio Grande Valley seamen in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

“With prayers on their lips and tears in their eyes, Valley Navy Mothers club members went ahead today with plans to provide Christmas surprises for Valley navy men stationed in the Phillippine and Hawaiian islands,” a Dec. 8, 1941 Monitor article describes the scene.

It was the day before, on Dec. 7 — “a date which will live in infamy” as President Franklin D. Roosevelt said — that America came under attack by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor.

As far as Emma and the other mothers knew that day, they were wrapping up Christmas presents for boys who were floating dead in the shark infested waters of the Pacific Ocean.

“What we can do, I don’t know,” she told The Monitor, which at that time published as the Valley Evening Monitor. “Until we receive some instructions we can only pray that our boys have come through safely.”

An article that ran a few inches away from the report on Emma and her cookies named about two dozen of those Valley boys. The article reported that three of the men were stationed away from Hawaii.

“The rest, as far as available lists here can be confirmed, are at Pearl Harbor,” it read somberly.

There was C. Max Hill, of McAllen, and Walter Sigler, who were aboard the USS Indianapolis. Leonard Krska, of Edinburg, and Otis Lomax, of Pharr, were stationed at a submarine base. Jess Cummins Jr., of McAllen, was at naval radio station Mantipi.

There were more names on the list, and more that belonged on it.

“While there are many more from the Valley who are in the war zone, these were all listed by the Valley Navy Mothers club, reported by Mrs. Emma Jones,” the article said. Readers were encouraged to send names of sons in the Navy with where they were stationed to Aunt Emma as soon as possible.

Emma Jones would report that information as she got it, and it would join a stream of reports on the Valley’s involvement in World War II. Over the next week, the Valley prepared itself seriously for the possibility of attack locally, citizens surged to volunteer physically or financially and those mothers learned, terribly slowly, which of their sons were alive and which were not.

On Dec. 8, while the Navy Mothers club was weeping and wrapping Christmas cookies, The Monitor reported that armed guards were stationed that day at approaches to the Hidalgo international bridge.

General Pedro Lopez Tafoya deployed the Reynosa garrison to defend the southern approach to the bridge; Valley Bridge company Manager Joe Pate put the north side under civilian guard.

In downtown McAllen the United States flag was displayed in front of every business place, and five minutes after FDR’s radio address, in which the famous “infamy” speech was delivered, a man rushed into the Alamo post office to purchase a $1,000 defense bond.

“It’s the most I can do,” Postmaster Howard L. Smith claimed the man said.

F.P. Britt, a winter visitor in Brownsville, would later report to The Monitor that he was picking up seashells on Boca Chica Beach on a Sunday afternoon when he encountered what the paper interpreted as a favorable auspice from Neptune.

“At almost the same minute that Japan’s attack on the United States was announced by radio, Mr. Smith picked up a shell on which erosion had etched a perfect ‘V,’ the paper reported.

Despite Britt’s favorable looking shell, tensions in the Valley remained high and much of life in the Valley for the next week would be defined by those tensions, playing out on the front page of the newspaper while Aunt Emma and the rest of her Navy Mothers kept waiting on news from their boys.