BY JULISA NEVAREZ

Marina, Malina, Malintzin, Malinchi, Malintze and Malinche — these names may sound or look different, but they all describe one person.

Camilla Townsend told the story of la Malinche, a native Mesoamerican woman who played a key role in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, at the latest event of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley’s Rondel Davidson Endowed Lecture Series held virtually Tuesday evening.

Townsend is a history professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey, and has done extensive research on Nahuatl, the Aztec language, and the writings left by Native American historians. Her presentation was entitled “La Malinche, according to the Indians.”

Townsend explained that those names are correct when referring to the woman the Spaniards called Marina or Doña Marina. The indigenous knew her as Malina or Malintzin, while the Spaniards eventually referred to her as Malinche. In Mexico today, her name symbolizes the essence of treachery and betrayal based on her actions in the 1500s.

Throughout the event, Townsend discussed the history of la Malinche, bringing clarity to the woman who was lost in translation in the years during the Spanish conquest of Mexico and afterward.

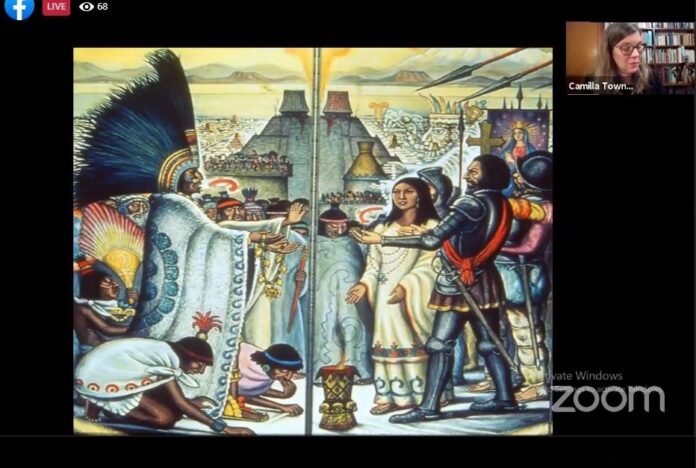

“Malinche tends to be known as a sneaky, sexy person who hops up on the horse with Cortes, and they’re about to ride off into the sunset or the forest to do you-know-what,” said Townsend, who studied at Rutgers University and has been teaching there for 14 years. “This image is very common in Mexico. Malinche, in their world, is not someone you take very seriously. So why does this real girl, who we shall get to know as an actually quite nice and a very interesting person.

“Why does she have such a reputation?” Townsend rhetorically asked viewers.

She explained that Malinche is closely associated with the Aztecs and their bad reputation involving human sacrifices, along with the fact that on a deep psychic level, many people of Mexican descent can’t help but feel a sense of grief when they think of their ancestors giving themselves to their enemy, Hernando Cortes, who ended the reign of Montezuma and the Aztec Empire.

“The psychic impact of these stories is directly related to who we imagine ourselves to be,” Townsend said, who specializes in early Native American and Latin American history and early America. “So, now besides the bad reputation of the Aztecs, the Malinche is also caught in this discussion. She’s forever known as the figurative great-great-great-great grandmother who gave herself to this brutal, figurative, imaginary group — but it isn’t true.”

La Malinche was born in Coatzacoalcos, Mexico, an area that had not yet been conquered by the Aztecs, but were looking to do so. Her people spoke Nahuatl, the same language as the Aztecs, though they were not Aztecs — they were under threat from the Aztecs when Malinche was a child.

In the wake of an attack, Malinche was enslaved, and in the 16th century, once a slave was taken, they were tied to a stick and prepared for sale. Malinche was sold in the town of Shikalanko along the Gulf Coast and ended up in today’s Villahermosa, Mexico, living among the Mayans as a slave girl.

“Today, Villahermosa is a beautiful town, but for Malintzin it was not a time of peace and loveliness,” Townsend said. “It was no vacation. Malintzin’s years in the time that she was taken, we think, between the age of 8 and 12, these were not easy years. She was a slave, she was a sex slave.”

Throughout the lecture, Townsend used Malinche’s many names.

The Spaniards arrived in Malinche’s area when she was a teenager. Spaniard Jeronimo de Aguilar acted as a translator between conquistador Cortes and the local Mayan people, and the Mayans offered 20 slave girls to them as a sign of peace — one being Malinche.

“I wish I could show you a photograph of Malintzin in that moment,” Townsend said. “She had already lost her home years before. Now suddenly she was being transferred yet again, to even more terrifying, foreign beings. There are lots of line drawings in the codices, there are lots of European paintings, but I don’t think they do the trick. They don’t help us to catapult ourselves into that moment to think of her as what she was: a real person. She was younger, we think, than any of you who are listening; maybe 17 years old, (with) the weight of the world on her shoulders.”

The Spaniards accepted the 20 girls and brought them along as they traveled further along the coast. De Aguilar could not talk to the local people after they left the Mayans and within days the Spaniards realized that Malinche could communicate with the local people because she was born into an Aztec, Nahuatl-speaking world.

“So, there she was, this teenage girl who had already presumably been raped by the Spaniard who she’d been given to,” Townsend said. “Cortes came to her and said, ‘I hear you talking to these local people, so I know you can serve as our translator. If you do that, you will come and work directly for me. You will not be subject to any of these men. You can help us. You can help me get to the Aztec king where I want to go. Or you can refuse to do that, and I leave you to your fate.’”

“So, if she wanted to stay alive and she wanted to cease to be subject to daily rape, she had a path before her. Remember, also that the Aztecs he [Cortes] wanted to possibly conquer were her people’s enemy, the reason why she herself had been sold into slavery, so she said, ‘Yes, I will be your translator.’ And she did, she was a fantastic one.”

Centuries later, after the wars of independence, when Mexico broke away from Spain in 1810, anyone who had sided with the Spaniards or helped them — even those who had worked to make peace with the Spaniards became suspect — accused of being traitors.

Knowledge of Malinche’s situation was long gone. People began to write a whole different set of stories in which Malinche was suddenly perceived as an unpleasant person, but it does not match the history of the indigenous people, who perceived her as a respected figure. No one remembered what her life had really been like or what her contribution really was.

“What I hope is clear, is that people today, whether they are descendants of Spaniards or Indians or neither one or both, should actually be quite proud of her,” said Townsend, who has published her own findings of Malinche and continues to study Native American history. “She was a gutsy little thing who handled the worst circumstances with dignity and who probably saved a great deal of many lives.”

Julisa Nevarez is a student at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to correct information about Townsend.