BY NORMAN ROZEFF

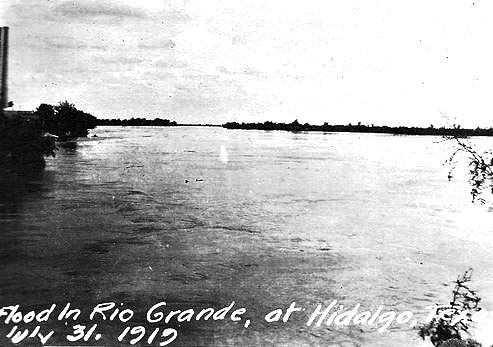

Judging by its slow and gentle behavior today, it is hard to envision its vastly different appearance less than a century ago, but this indeed was the Rio Grande.

Reflect first in its name and how it came to be. Rio Grande is, of course, Spanish for great or grand river. In times past it was also called in Mexico Rio Bravo del Norte. Bravo is Spanish for wild, ferocious, harsh. That former name for the river speaks millions.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, “The Pueblo Indians called this river P’osoge, which means the “river of great water.” In 1582, Antonio de Espejo of Nueva Vizcaya, Mexico, followed the course of the Río Conchos to its confluence with a great river, which Espejo named Río del Norte (River of the North). The name Rio Grande was first given the stream apparently by the explorer Juan de Oñate, who arrived on its banks near present-day El Paso in 1598. Thereafter the names were often consolidated as Río Grande del Norte. It was shown also on early Spanish maps as Río San Buenaventura and Río Ganapetuan. In its lower course, it early acquired the name Río Bravo, which is its name on most Mexican maps. At times it has also been known as Río Turbio, probably because of its muddy appearance during its frequent rises. Some people erroneously call this watercourse the Rio Grande River.”

River is redundant as the word Rio in Spanish has the same meaning.

The Rio Grande is 1,896 miles in length, making it the fourth or fifth longest river in this country. It begins its long journey to the Gulf of Mexico as a small and obscure stream in south-central Colorado in a watershed to be found in the western part of the Rio Grande National Forest.

It soon joins other non-descript streams to warrant the honor of being named a river. This occurs east of the continental divide below the base of Canby Mountain. Naturally the volume of the rushing waters varies annually depending on the snow melt. A major tributary feeding the Rio Grande is the Rio Chama which originates in southern Colorado. Its flow was augmented by man-made diversions that took a decade, 1966-1976, to complete.

These diverted waters move by tunnels from three San Juan River tributaries in Colorado. The San Juan River is itself a tributary of the Colorado River. In earlier times the great river’s flows would not be augmented in Texas until many miles more.

Approximately 1,248 miles are located along the southern border of Texas. The first major addition to its waters is from the Pecos River which originates in eastern New Mexico in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and joins the Rio Grande near Del Rio.

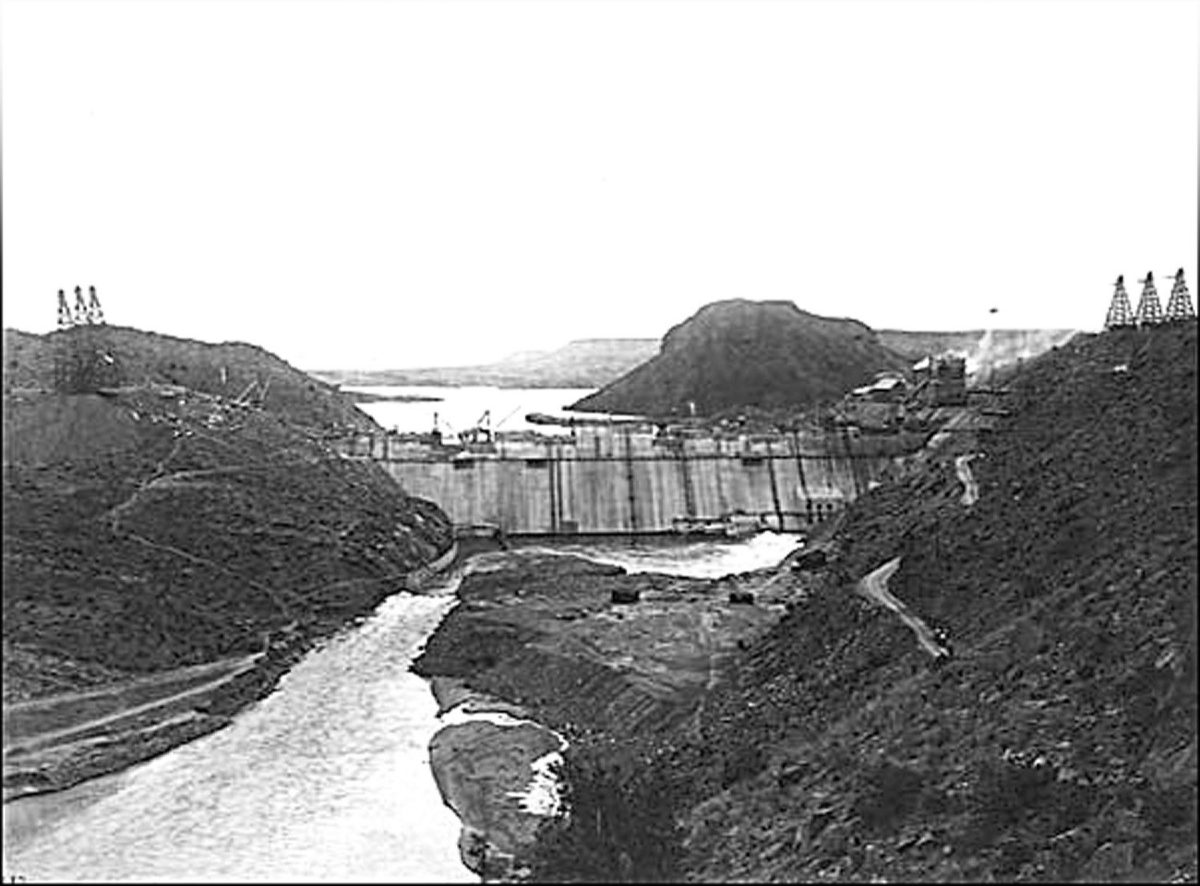

Four dams located in New Mexico currently diminish its once heady contributions to the waters of the Rio Grande. It was the rivers of northern Mexico that once greatly impacted the volume of Rio Grande flows. Farthest west was the Rio Salado, itself fed by five rivers originating in Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas.

Next was the Rio Conchos, another river being fed by five tributary rivers originating in Chihuahua and Durango. Downstream of it was the Rio Alamo with waters starting in Tamaulipas. It was upstream from a very significant source.

This was the San Juan River. Its waters originated in the three Mexico states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, and Coahuila. Its prime tributary was the Río Pesquería of Nuevo León. There are 17 smaller creeks in Texas that periodically flooded and emptied into the larger river and eight originating in Coahuila that did the same.

Additionally 22 rivers and creeks in New Mexico and three rivers in Colorado added their waters to the Rio Grande watershed. With these unimpeded tributaries flowing in to the Rio Grande for eons, it is easy to visualize why the river was termed Bravo.

As the river for centuries experienced periodic flooding it deposited huge amounts of sediment into and adjacent to the Gulf of Mexico to form a classic delta. Our delta mostly formed in the Holocene, the geological epoch that began after the Pleistocene at approximately 11,700 years before AD 2000 and continues to the present. Scientists put the beginning formation of our delta about 7,000 years ago.

It is presently not in a construction phase as, due to the many dams and agricultural irrigation usage now in its drainage basin, sedimentation has been sharply reduced and shore erosion is occurring and is abetted by periodic hurricanes and tropical storms.

The numerous periodic floods meant that the river would break out of its older courses and form new ones. These old river runs are still with us today and are recognized in our resacas. Their geometry is far from the nearly straight course that we see in the river today. They take the shape of typical river meanders found around the world. To quote from a Scientific American Magazine article on the subject “The striking geometric regularity of a winding river is no accident. Meanders appear to be the form in which a river does the least work in turning; hence they are the most probable form a river can take.”

The word meander derives from a winding stream in Turkey known in ancient Greek times as the Miandros and today as the Menderes. Lakes formed in cutoff resacas are frequently termed ox bow lakes. This term derives form the u-shaped portion of the yoke used in ox teams. The Spanish word resaca is derived from the verb sacar which translates in English to draw out, pull out and take out.

Valleyites apparently modified the term to signify a recurring river course that was a “takeout” from the normal one.

The first Europeans to see the river were likely Captain Alonso Alvarez de Pineda and his crew in the autumn of 1519. Some historians have likely and erroneously connected the Rio Grande with the Rio del las Palmas. More recent historical research has now declared that the Rio de las Palmas is actually the Pánuco River reaching the Gulf at Tampico.

The second Europeans to view the river, in a depleted period in November 1535, were Núñez de Cabeza de Vaca, two other white men, and a Black slave who wandered in the wilderness for seven years as the last survivors of an ill-fated Spanish settlement mission originally destined for the Pánuco but driven off-course to Florida by a storm.

More than one tribe had told Cabeza de Vaca of the seven cities of Cibola that contained riches beyond imagination. De Vaca retold this to the border Spaniards including provincial Governor Vásquez de Coronado at Compostela. In January 1540 the Viceroy by royal authority granted the governor the authority to man a military expedition to search for the fabled cities. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado y Luján, the leader of the expedition was said to have reached as far as present-day Kansas.

His search was in vain, for no treasure cities were ever encountered. The journey did lead, however, to the eventual colonization of the areas north of the river into what is now New Mexico. This did not occur in an organized manner until 1581. It would be the very first effort to colonize an area north of the river.

It was in January 1747 that, under the charge of José de Escandón, seven separate armed detachments numbering 765 men in total,marched for about 30 days to reach the mouth of the Rio Grande. They reconnoitered a region of almost 120,000 square miles ranging from Tampico in the south to the Bahía del Espiritu Santo, Spain’s northernmost fort in Tejas. Escandón himself arrived at the river’s mouth on February 27. He then had constructed a barge so he could cross to the river’s north bank.

The expedi- tion had two primary objectives. One was to map the heretofore unknown territory, and the second was to exhibit a show of force to the native inhabitants of the region.

Before the coming of the railroad to the Lower Rio Grande Valley (LRGV) in 1904, the river remained largely unchanged by man. As early as 1770 cattle raising and farming constituted the chief industries of settlers both on the south and north banks of the river. The first settlers of the heretofore neglected

LRGV were led by José de Escandón y Helguera, the Count of Sierra Gorda. It would be in February 1749 that the first of the lower Rio Grande settlers came out of Nuevo León to make the town of Nuestra Señora de Santa Ana de Camargo at the junction of the San Juan and Rio Grande Rivers.

Others soon learned of the fickleness of the river. Carlos Cantú under Escandon’s command founded, on 14 March 1749 with 297 inhabitants, the settlement named Villa de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Reynosa. Due to major flooding of the settled area “on the 4 July 1802, they decided to move five miles to the east keeping the same margin between them and the Rio Grande.” This grew into the city that we know today as Reynosa.

With a number of villages now on both sides of the river, ferry traffic became common, first for the cattle ranchers moving herds and their by-products and later for the salt deposits northeast of Reynosa. During high water periods fording and ferrying became dangerous enterprises.

For century following century, millennium following millennium, the river alternately flooded and subsided. As it did so, it deposited its sediment both in its depths and along the banks where it had overflowed. As a result the bed of the river and the river itself rose to a higher elevation than the surrounding delta. The river’s heavier particles, including sand, settled out first and its lighter particles, clay, were carried a greater distance from the river.

These results are with us today in the U. S. Depart- ment of Agriculture’s Soil Survey results. Along the river and resacas are to be found the best drained and most productive LRGV soils, the Laredo silty clay loams, and at a greater distance from the river the various clay association soils such as the dense, with low infiltration rates, Harlingen and Mercedes clays.

We learn from “Tilden’s Voyage to Laredo in 1846”, edited by Stan Green, that some of the earliest commercial activity on the river took place after New Spain won its independence from Spain in 1821. He relates “In 1828 John Davis Bradburn, an American holding a colonel’s commission in the Mexican Army and Stephen M. Staples, whose family had a business house in Mexico, convinced the governments of Chihuahua, Coahuila-Texas, and Tamaulipas (Nuevo Leon would not acquire river frontage until 1892) to grant them a 15 year monopoly for Rio Grande steamboats and horse drawn vessels. They managed to send one steamboat upriver.

Henry Austin, Stephen Austin’s cousin, took it a step further. He acquired the Tamaulipas concession, took the steamboat Ariel to about Mier in 1829, and did some trading between Camargo and Matamoros. His pilot Alpheus Rackliffe stayed on and, along with a couple of others engaged in flatboat traffic in the 1830s.”

With the onset and advancement of civilization, the deep waters of the river would have positive effects. A major turn of events was to be the commencement of the Mexican-American War. Following the American battle victories at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, General Zachary Taylor’s army occupied Fort Polk at Point Isabel, Fort Brown, and the city of Matamoros.

American war strategy was to land a major force at the port of Veracruz and advance towards Mexico City while a second pronged advance would be made from the north of Mexico by the army commanded by General Taylor. In order for Taylor to succeed he would need to move both men and matériel to the northwest.

His troops marched to Camargo, the jumping off point to an attack on Monterrey, on the existing road south of the river in Mexico. As Pat Kelley writes in his book, River of Lost Dreams, “The war’s importance to the Rio Grande cannot be overestimated.” The fact was that Taylor called for boats and experienced river boatmen to move his supplies upriver to Camargo.