BY NORMAN ROZEFF

It is hard to imagine a greater disconnect than occurred here in the summer of 1916. That is the period when national guard troops from a number of northern states were dispatched to the Rio Grande Valley to ensure domestic tranquility in a period of wild abandonment.

It began as border unrest commencing in 1911 and was fed by the revolution occurring in Mexico as it began to spill over north of the river delineating our southern boundary. In 1914 President Woodrow Wilson authorized the invasion of Veracruz, ostensibly due to a national diplomatic slight but in reality to protect American oil interests in the Tampico area. After this issue was resolved by November 1914, some U.S. Army troops were then stationed at the border with Mexico.

Tensions continued to escalate as a number of Mexican warlords contended for the presidency. In the spring of 1916 an murderous intrusion by Pancho Vila at Columbus, New Mexico, forced the president to send a punitive force south to apprehend this desperado. On May 5, 1916, Glenn Springs, Texas, was attacked by Mexican nationals. Some 80 Mexicans, some say including some Texans, celebrated Cinco de Mayo by crossing into Glenn Springs, Texas, and killing three United States soldiers who were guarding a wax factory. President Wilson then initially activated the national guard units Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona into federal service to help protect the border.

When the situation didn’t improve, on June 18, 1916, he ordered the mobilization of the Guard of the remaining states for the same purpose. The War Department specified which Guard units (by regiment) the federal government wanted for service on the border.

One of the national guard units was that of New York. Many of its soldiers were from New York City and included some illustrious individuals who never dreamed that they would be called to active duty. It didn’t take long to transport the units of 14 states to the southern border. By July 1916 it was reported that 100,000 men were camped on the border and 58,000 more were still at state mobilization camps.

Initially the New York contingent had mustered at Camp Whitman, which was at Fishkill, New York among the picturesque and cool Catskill Mountains. Trains soon carried them south through San Antonio and then into the Valley. What a contrast the soldiers must have experienced. Here was the Valley getting hotter with each passing day, and especially so in their woolen uniforms totally unsuited for this climate.

The New York Guard Division (later designated the 6th Division) sent south consisted of the First Brigade having the 2nd, 14th, and 69th Infantries; the Second Brigade of the 7th, 12th and 71st Infantries; the Third Brigade consisting of the 3rd, 23rd, and 74th Infantries; the Field Artillery Brigade with its 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Field Artillery; 1st Signal Battalion; the 1st and 2nd Battalion of Engineers; the First Cavalry; 1st, 2nd, & 4th Field Hospital; 1st through 4th Ambulance Company; Supply Train and Bakery Companies. There were also at least two bands, albeit of modest size. The troops would be stationed in McAllen, Mission, and Pharr.

The Second Brigade, under Brig. Gen. George Dyer, had a peak number of 10,290 men. It arrived in McAllen together with the New York Division commander, Major Gen. John F. O’Ryan, on July 2. The First Brigade, with 3,950 officers and men, was commanded by Brig. Gen. James W. Lester. Its 14th Infantry arrived in Mission on July 3. The Third Brigade, with 4,120 officers and men were under the command of Brig. Gen. William Wilson, Its 74th Infantry arrived in Pharr on July 10. The Division’s beginning days in the region was described in an official document: “The first six weeks at the border were strenuous in the extreme.” Getting acclimated to the sun and frequent torrential rains was a challenge for these doughboys.

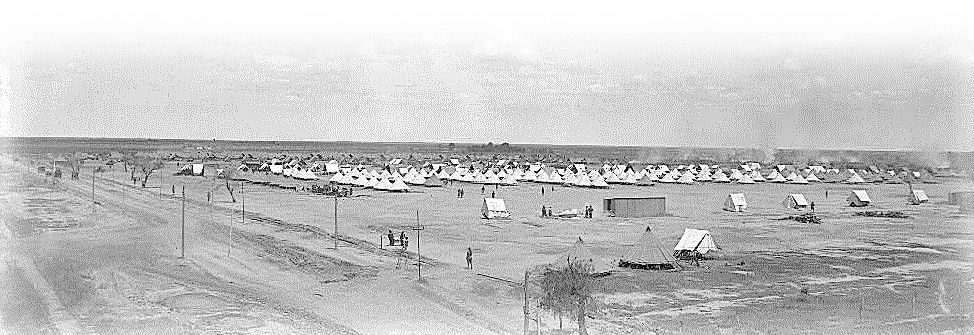

The infrastructure of these newly created towns was primitive at best. The War Department was to establish camps for the soldiers in relatively undeveloped scrub brush outside of the city limits. The first job of the Valley Hispanic laborers was then to clear out the multitude of thorny vegetation where the camps were to be erected. Mostly large canvas tents with wooden floors were then strung up, but the buildings for officers, food preparation and other services would later have wooden framework and floors. There were also some pup tents without flooring. In addition, to make the habitat livable, roads, drainage ditches, refuse dumps, incinerators, and latrines had to be constructed. Since the water systems of adjacent towns were not reliable, wells and pumping systems had to be installed.

The Gulf Hurricane of August 18, 1916, put the construction to a test. Only after the camps were firmly in place could training exercises commence.

In early August, elementary training with small arms and rifles was begun in area several miles removed from the camp sites and towns. This was followed by “hardening” marches or hikes and bivouacs. Eventually the units were taken on 100 mile marches over a 12 day period. Some of the locations where the bare-boned encampments took place were in remote ranches including those of Alton, Sterling, La Gloria, Laguna Seca, and Youngs (Santa Anita?) but also near Edinburg. The cavalry units went farther afield going north to visit even other ranches.

Artillery practice took place in a remote area near La Gloria. For the use of the newer 4.7” howitzer, only made available to the army in 1911, the NY artillery men had to go to Fort Brown where the artillery range was on the old Palo Alto battlefield. NY units also entrained on the single railroad track to Harlingen where special machine gun instruction and practice took place.

Initially, despite the inclement weather and marginal sanitation, sick call numbers were within reason. For the first month that the NY units were on the border the sick calls averaged 1.85 percent of the men. In late August however there was the report of two deaths, one soldier who was being treated in a McAllen sanitorium and another at the base hospital. A third death was reported of a sergeant who died accidentally while diving in a canal near Sharyland. In early September, at Mission, there commenced an outbreak of paratyphoid, an intestinal tract malady that we now know is caused by the Salmonella bacteria. It spread east and eventually 80 soldiers were stricken with symptoms of high fever, weakness, and loss of appetite.

Some were sent to San Antonio for treatment. Tainted food rations fed to the troops was undoubtedly the underlying cause. As a result of the disease outbreak the camp operation in Mission was shut down, and the soldiers there moved east to McAllen. While snakes were commonplace, few were of the venomous kind.

In addition to the fatalities noted above, the final tally of New York soldiers who lost their lives while stationed in the Valley includes two who died of accidental gunshot wounds, one who died after being accidentally kicked by a horse, four of unstated injuries, and 16 more who died of various diseases.