BY NORMAN ROZEFF

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the next installment in an ongoing series on San Benito’s Sam Robertson. Find previous articles at www.valleystar.com

The San Benito Sugar Company with Alba Heywood as president took out a full page advertisement. It stated “We cultivate the land and market the crops for the absent owner.”

It then went on to say that the San Benito Land and Irrigation Company had set aside 1,000 acres of choice irrigated land which will be cleared and planted to sugar cane by the San Benito Sugar Company, an organization formed for this purpose. With no qualms about making exaggerated claims, it continued, “Sugar cane has been a demonstrated success in the Lower Rio Grande Valley for over 30 years. It is a staple crop, involving no risk, and yields 50% to 100% net year after year.”

The company was offering the 1000 acres in tracts of five acres or multiples thereof, at $200 an acre, of which the purchaser would pay $100 in cash or easy installments and the crop pay $100. By July of 1910 Robertson was advertising for “Only Experienced Cane Growers to get three year leases of 50 to 500 acres of a 3,000 acre tract. Applicants must have large mules and be able to furnish their own tools and supplies.”

Gunplay and wild west antics were still part of everyday Valley life. In the same July 1910 month as a Harlingen Star printer was shot, a very serious event took place south of San Benito. Sam Robertson learned of a planned attempt on his life. He notified Rangers Carnes and Craighead in Harlingen. They laid plans to capture the bushwhackers. Ten individuals set out from San Benito on a Saturday night. They later split up into smaller parties. One group staked out a hiding place and was soon to encounter unknown contentious individuals.

In the ensuing gun battle Texas Ranger S. B. Carnes, deputy sheriff Henry Lawrence, and sometime Robertson employee, Pablo Treviño, were killed but not J. Zoll, a San Benito Canal Co. employee accompanying them. In continuing pursuit Earl West, who had also been deputized as a special ranger for this operation, was wounded but escaped death. In the dark and with the confusion of split parties, Craighead was later wounded by friendly fire in a case of mis-identification and was lucky to survive. All had been attempting to intercept Treviño’s cousin Jacinto, who, along with others, allegedly was on his way from across the river to conduct the assassination.

Robertson had seemingly extracted a statement from Jacinto’s eyewitness cousin, Hillario, that Jacinto was the murderer of a San Benito Canal company employee. While, at the scene of the confrontation come daylight, pursuers discovered blood from other than the victims; the stalkers, likely three in number, had escaped. Robertson at the time was out of town on business as his substantial San Benito house was about to be built.

In time, Treviño family versions and word-of-mouth of the affair would essentially turn the story on its head. A popular corrido on the subject added to the creation of a folk hero legend.

Briefly the alternative account has Jacinto, son of retired Mexican army Captain Natividad Treviño, seeking revengeful justice for the pistol-whipping leading to the death of his brother Natividad.

The beating, by San Benito Canal construction foreman Jimmy Darwin, had occurred at Los Indios on May 28, 1910. What precipitated this dastardly act was supposedly Natividad’s refusal to work on a particular day after putting in long hours as the carpentry shop foreman.

The day after Natividad’s death, Jacinto, with a borrowed pistol, was to kill Darwin. Two months later Jacinto was then said to have entered into an ambush set by his cousin Pablo, who may have been seeking the $500 reward for Jacinto’s capture. It was here that the lawmen along with Pablo were killed. The exaggerated number of reported rinches (rangers) present grew to 50-60 in some family accounts. Jacinto had previously found sanctuary at his father’s Santa Rosa Ranch in Mexico and escaped again to this site.

Even in Mexico he was leery of retribution by the powerful Rangers and possible some of their Federales Mexican allies. For seven years he was cautious in his movements. For the rest of his 66 years he remained in Mexico, fathering six children from his first wife and, after her death, four with his second wife.

In a footnote to the foregoing it can be added that the Los Indios relatives of Pablo did not claim his body for burial. He is buried in the nearby Las Rusias Cemetery. His grave bears an expensive Rock of Ages granite monument. Written in Spanish, the inscription on it translates, “Pablo Treviño died for a friend.” Obviously that friend was Sam Robertson.

Another near miss was to occur five years later during the height of Bandit Era depredations. On September 9, 1915 a disgruntled individual(s) took the opportunity to waylay Sam Robertson as he drove on Alice Road about eleven miles north of Brownsville at 3 a.m. in the morning. Three or four shots were fired. One knocked off his hat and still another penetrated the middle of the front passenger seat. Once again good luck rode with Robertson, as it did a month and half later when he was twice attacked, this time near the San Pedro Ranch 8 miles from Brownsville. It was well known that he carried sizable amounts of cash on paydays to pay his employees.

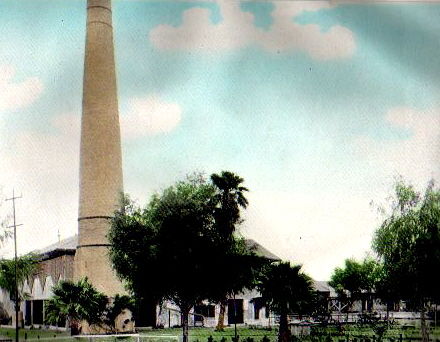

By October 1910 a bullish Robertson had purchased 5,000 acres from C. P. Barreda, a Valley resident of Spanish origin. This portion of the Barreda Tract lay directly east of the canal company’s land. The Louisiana Planter revealed some mill details in November. It was to be designed by A. F. Delbert with efficiencies being paramount to generate the least cost per pound of sugar manufactured. The maximum extraction possible would be looked for by Delbert, who had designed the Ohio and Texas Company mill two seasons ago. Part of this would be achieved by a crusher of special design. Delbert estimated that $208,355 would be needed for the turnkey construction job, $90,000 in cash. Conservatively he was assuming a sugar content of 185 lbs. per ton of sugarcane, that the cane would cost $358,636, and that the mill would net $203,333.88 the first year.

With 1,200 acres in cane by mid-November, the goal was 5,000 acres in 1911. The San Benito Sugar Company Plantation alone would have 2,000 acres of the “long sweet”, while the Watts brothers would have an equal acreage and Mr. Cowgill 800. The Cowgill Plantation was three miles north of San Benito near Nopalton. The Interurban railroad would be completed in time to connect to the St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico tracks in order to move cane to the mill. The latter would initially furnish cars and motive power for moving the cane crop, but the Interurban would soon have its own locomotives and freight cars.

In its 1/18/11 edition the Brownsville Herald featured a major advertisement from the San Benito Land and Water Company. It was a major promotion for San Benito. It invited prospective buyers to a train excursion, barbeque, music, and land auction. The ad proclaimed: “San Benito — population 1907 — nothing; 1911 — 3500. The wonderful growth of San Benito has astounded the most conservative. Less than four years ago San Benito was nothing but a mesquite brush; today it has a population of 3,500, Water Works, Electric Lights, and will have sewerage in the near future. A $400,000 sugar mill will be in operation by next season. Business houses and residences are going up as though by magic. Fully $100,000 is now being spent in the construction of same. The San Benito and Rio Grande Railroad (sic), an interurban now being built, will make this wonderful city its headquarters. If San Benito has done this in less than four years when the Valley was only in its experimental stage, now that the future of the Valley is assured one can readily see San Benito a city of 10,000.

With the Greatest Irrigating Canal in the South at its very doors we say to you that an investment in real estate here is not a Gamble or Speculation, but a Certainty. The terms ARE EASY – 1/5 cash as soon as sale is made, then 5% per month until 1/3 of purchase price has been paid – balance 1,2,3 years all to bear 6% interest.”

In March S. C. Cowgill left Brownsville for a month long visit to Cuba to study cane cultivation. Shortly thereafter, it was announced that the contract had been let for San Benito’s $500,000 mill. A Mr. Palfrey, a Louisiana expert sugar man was to be general manager. Operating costs for the first year were estimated to be $100,000, consisting of $40,000 payroll and $60,000 labor and material.

Charles Barber canvassed stock for this mill, $150,000 in all. Barber’s plantation was to the west of town near present day North Zillock Road. In the 1980s the San Benito News wrote of the civic-minded citizens of the city in 1910. “The San Benito Commercial Club, the forerunner of the Chamber of Commerce, raised $50,000 (a lot of money in those days) to help provide facilities to refine sugar.”

Sam was a member of this organization. Conceivably the mill was to be designed for efficiencies and year-to-year enlargements.