BY NORMAN ROZEFF

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the next installment in an ongoing series on San Benito’s Sam Robertson. The previous parts can be found at www.valleystar.com.

In the Mercedes Tribune, 9/17/37, Robertson wrote an article titled Opening the Last Frontier. From this account we learn in greater detail the events preceding his sugar ventures.

“I came to the Valley in 1903 to take a contract for the construction of bridges and track laying on the new St. L. B. & M. Railroad which was being promoted by Colonel Uriah Lott and financed by Mr. B. F. Yoakum, Johnston Bros. and the St. Louis Union Trust Company, group of financiers

Plunge On A Shoestring

Charles Hobbs, Lewis Mims, Captain Bill Lewis and myself organized the Southern Contracting Company to take the sub-contract under Johnston Bros. to build the track and bridges from Robstown to Brownsville and Harlingen to Sam Fordyce. I had been interested in irrigation in East Texas, Louisiana, Wyoming, Colorado and Utah, so decided to take a plunge in the Lower Valley on a shoe string, I knew rice was a failure, but I felt sure the soil and climate was fine for other crops. I was somewhat handicapped on account of having sustained a compound fracture of my right leg and fractured three ribs in a railroad wreck at Kingsville, and it was difficult to get around and look the country over. I had a white horse which would lie down and allow me to climb on his back and at odd times I scouted over hundreds of miles of the country between Raymondville and Brownsville on the east and Sam Fordyce on the west. I was practically broke but felt sure I could interest the necessary capital.

“Bessie” Later San Benito

“In May, 1904, we reached Bessie (now San Benito) with the track. I met Messrs. James L. Landrum and Oliver Hicks whose families owned several thousand acres around Bessie. I was on crutches so they rode with me on our construction train. I discussed my plans for the irrigation of their lands and the building of a town at San Benito, then a narrow place in the jungle. They gave me a verbal option on their lands including the present town site of San Benito.

It took me almost three years to finance the project, but Hicks and Landrum’s verbal contract was better than a United States Government Bond. About this time I made a verbal contract with about twenty-five Mexicans for canal rights of way to be deeded when the canal was built. All verbal contracts were kept to the letter.

Irrigation, railroads, schools and civilization does not seem to have improved the honesty and reliability of people in the Rio Grande Valley since 1904. It was my plan to interest Messrs. Yoakum, Johnson Bros., Sam Fordyce, and others associated with them in building and land development.

I only wanted the contract for canal construction. Mr. Yoakum told me to hop to it and he would give me a reasonable amount of help. The railroad civil engineers were all friends of mine and I got a tremendous amount of engineering data from them. Capt. Mindola, a Mexican engineer, gave me river data. Jim Malaby, of the Mexican National Lines and Mr. Follett of International Boundary Commission gave me valuable maps and data. I “mooched” at least $50,000 worth of engineering information from friends.

“Old Man River” On Rampage

On the 16th of September, 1904 while laying track near Havana, just east of Sam Fordyce, “Old Man River” rose twelve feet in two hours and I knew we were in for it. I got a hand car and six big (men) and started for Harlingen Junction where we had just finished a bridge across the Arroyo Colorado.

I had driven piles for sub-foundations and knew piling furnished by the Railroad Company were forty feet too short to stand a major flood because it did not penetrate the quicksand. I had built false work to erect steel super structure and knew the drift would accumulate above the false work and carry out the bridge and cause my friends, the Johnston Bros. a big loss.

So, I rushed the bridge with my hand car and (men) and picked up some more men in Harlingen and sawed false work down and let it drop into the Arroyo Colorado. The flood started down the Arroyo within the hour after I had destroyed the false work obstruction.

Bridge, Tracks, Go With Flood

But the channel span was too narrow and the steel span and concrete abutments were swept out quickly. We lost eighteen miles of track and roadbed between Harlingen and Havana and about twelve miles between Harlingen and Raymondville.

This flood showed us that we would need flood protection as well as irrigation. So, in preparing my data to aid in promotion, I traced out high water marks all over the entire delta and during the flood we had engineers take approximate heights of the Rio Grande at Sam Fordyce through the Arroyo Colorado, through the Rio Tigre on the Mexican side and a gaugeing station at Los Rucios (sic) near San Benito pump. Mr. Jim Malaby of the Mexican National Railroad lines furnished me with much flood data.

River Reverses Tactics

In February, 1905, we had a norther when temperatures dropped to 16 degrees above zero and the water tank at Catherine burst a hoop with the freezing water. The Rio Grande looked like it was going dry. It got down to about 3000 second feet at Los Rucios in February, 1905 and by May of 1905 it shriveled to 1100 cubic feet per second at Los Rucios. So we knew that if all the country in the delta on both sides of the Rio Grande were to be irrigated, it meant vast storage dams on the Rio Grande and its tributaries on both the Mexican and Texas side of the river. I reported the bad features to Mr. Yoakum and submitted a rough plan to take care of it all.

About that time the United States Agricultural Department reported that with proper seed, irrigation and cultivation, forty tons of sugar cane per-acre could be produced and the juices in the cane contained 18 per cent of saccharine matter. This fine report made the flood and irrigation difficulties look small. But the Government report proved to be about 90 percent bunk. However, a real research chemist could have cured a multitude of our sugar cane troubles.

Financiers Visit Frontier

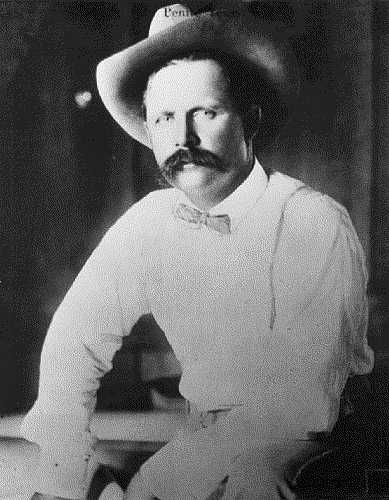

In February, 1905, while I was building a Railroad Loop near Sarita, Mr. Yoakum came by with a train load of investors to look into land and irrigation possibilities. He picked me up. I was on crutches, unshaven and looked like a tramp. He introduced me to his crowd of “Brass Hat” investors as his irrigation engineer.

On the train was Mr. John Hays Hammond, an internationally known civil and mining engineer, Col. Sam Fordyce, W. K. Vanderbilt, Judge Morgan O’Bryan, Mr. Bixby, Mr. Brookings, Mr. Tom Carter, Mr. Tom West and dozens of other financiers of St. Louis and New York.

Mr. Hammond proceeded to put me under cross examination for about three hours with a dozen others butting in. They had me scared stiff, but I never concealed any of the difficulties but offered what I thought was a solution. I never visualized twenty-five years of revolution, communism, socialism and atheism in Mexico or I would have been less “cock-sure.”

Mr. Hammond said, “Yoakum, Robertson seems to have a good scheme and he does not try to conceal defects. I think the irrigation should proceed in a big way, and I will come in on it.” That was the real beginning of the American Rio Grande project. But court decisions in regard to water rights coming out of the Texas Supreme Court caused them to reduce tremendously the contemplated acreage.