BY NORMAN ROZEFF

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the next installment in an extensive series on Sam Robertson. The preceding parts can be found at www.valleystar.com.

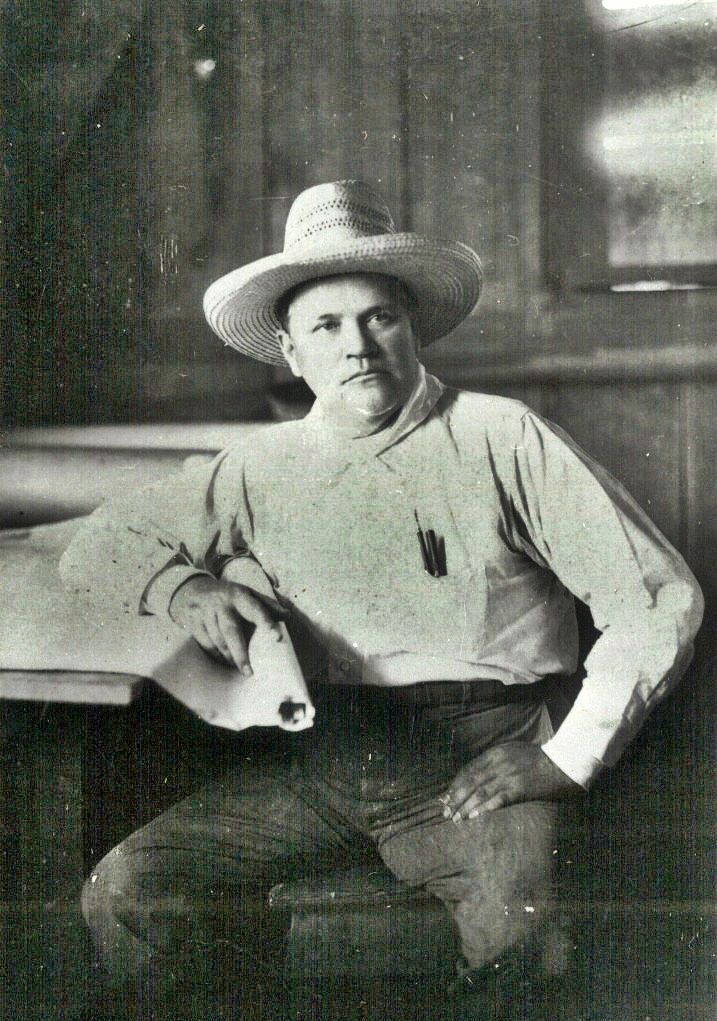

Once located in the LRGV, Robertson would become involved in a number of enterprises that called for his expertise. One of the first was when he became a partner in purchasing one of the first successful canals constructed in the Valley.

This was the five mile long Santa Maria Canal that serviced 5,000 acres. It had been constructed by 1897 by Judge Emilio Forto and the Longoria Brothers. Purchased in June 1905, the partners with Robertson were Walter J. McNeil, Charles Hammond, and LeGrande W. Jones. The entity became the Santa Maria Irrigation Company. It also purchased adjacent land from, J. L. Halbert, F. S. Champion, and a man named Perez.

Soon 450 acres had been cleared and another 100 was in the works. After three years had passed a new corporation was formed with $20,000 capital. Its new owners were Frank Rabb, Walter A. McNeil, Edward Palmer, and S. J. Schnorenburg. There entity was renamed the La Feria Mutual Canal Company. It would later merge with Cameron County District No. 3.

Later in September 1905 Robertson would become involved in constructing the first phase of the Valley’s largest irrigation project. It was that of the American Rio Grande Land & Irrigation Company.

With a capital stock of $1.5 million its plans were to prepare and develop 125, 000 acres of land from the river south of Mercedes to just north of La Villa. He had been contracted in January of that year to grade canals and laterals south of the railroad seven miles to the river. A 500 foot swath would be cleared of brush and then the main canal of 145’ width would be

dug 15’ to 20’ deep. This was completed by November 1, 1905. The canal had the capacity to handle more than 100,000 gallons per second. Sam’s many activities even took him from time to time into Mexico. He formed an acquaintance with Senor Limantour, Secretary of Finance in Porfirio Diaz’ cabinet, and he also became acquainted with Francisco Madero who overthrew Diaz, and was himself assassinated. He also met Madero’s sister. Next on his agenda would be a project closer to what would become his home.

The Berta Cabeza Middle School history compilation tells us: “He also learned that, similar to the north bank of the Rio Grande, the resaca banks were slightly higher in elevation than the surrounding land. Robertson envisioned a gravity irrigation system with the resacas serving as the main canal. He would dig a canal from the Rio Grande to the Resaca del Rancho Viejo, build two to four foot high levees on each side of the resacas, and construct dams at intervals to let the water down gradually.

Canals and laterals would distribute the water to the various farm tracts to be irrigated. For land too high in elevation to be watered by the gravity system, he would construct a “high line” canal to be filled by pumps. Robertson reasoned that the pumps would provide additional protection when the level of the water in the river fell below the intake of the gravity system (it turned out that water had to be pumped most of the time). He would purchase the land and subdivide it into farm tracts. Finally, he envisioned a town at the intersection of the Resaca de los Fresnos and railroad tracks as the hub of his development.

Except for the land on which Robertson proposed to construct the head gates and pumping plant, and a relatively small portion of the right-of-way needed for the canal to the resaca, all the land needed for his system belonged to the heirs of Stephen Powers. Of the Powers’ lands, the portion most needed for his system belonged to the Hicks, Combes, and Landrums. Robertson’s problem was that he had no money to construct the system, much less pay for the land. Robertson met with all the landowners and told them of his plan. He offered to purchase their land but told them he would need time to raise the money. Robertson and the landowners agreed on a price, and the landowners agreed to give Robertson the time he requested to raise the money to purchase their land. From James Landrum and Oliver Hicks, he was able to obtain 13,000 acres at a price of just over $3.00 an acre.

By November 12, 1906, Robertson had formed the Bessie Land and Water Company and had cleared one mile of the resaca. By early March 1907, he had cleared nine miles of the resaca but had exhausted his funds and had not yet exercised the purchase agreements. Needing additional capital, Robertson approached Alba Heywood, W. Scott Heywood, and Oro W. Heywood — brothers who had struck it rich at Spindletop — about investing in his project. The three Heywood brothers, former vaudevillians, had invested in the venture to drill for oil at Spindletop. Soon after the oil started flowing, they rushed to the field. Sam Robertson knew the Heywoods from his day constructing earthen dikes around their oil storage tanks. Probably through Spindletop, the Heywoods (and possibly Robertson) knew W. H. Stenger, Ed F. Rowson, and attorney R. L. Batts, all of whom would later play a role in San Benito’s development. In 1902, the Heywoods struck oil near Jennings, Louisiana. This was the first oil discovery in that state. The Heywoods also owned an oil field near Breaux Bridge, Louisiana.” The capitalists announced plans to put in a pumping station and 12 miles of canal south of Bessie (later to become San Benito) in October 1905. Little more than a train stop, Bessie was named for the daughter of the railroad’s financier, Benjamin Franklin Yoakum. When a post office with the name Bessie was later submitted to the Postal Department it was rejected since the name Bessie already existed in Grimes County, Texas. Robertson was to plat his town in 1907, and at first he named it Diaz for the long-time president of Mexico.

He later changed his mind. It was a former cabin boy on a Rio Grande steamboat, now a 69-year old cook in the surveyors’ camp, that suggested the name of San Benito. In doing so he wished to honor his former patron, Benjamin Hicks. One account explains the naming with this rationale: Moreno combined the given names of Robertson (Sam or “San”) and Hicks (Benny), whom he called “Don Benito.”) On April 16, 1907, Robertson became postmaster of the new town of Diaz. When it was renamed San Benito, he was commissioned postmaster again on May 20, 1907.

Thirteen months after its announcement, Sam Robertson’s Bessie Land and Water Company had completed the first mile of its main canal. It was 100 feet in width. One hundred men were at work on it. Additional labor was sent to Bessie to make bricks for the pumping plant, since 16 miles of narrower laterals were to follow. Fifteen miles of the San Benito canal had been excavated with a completion date forecast for July 1907.

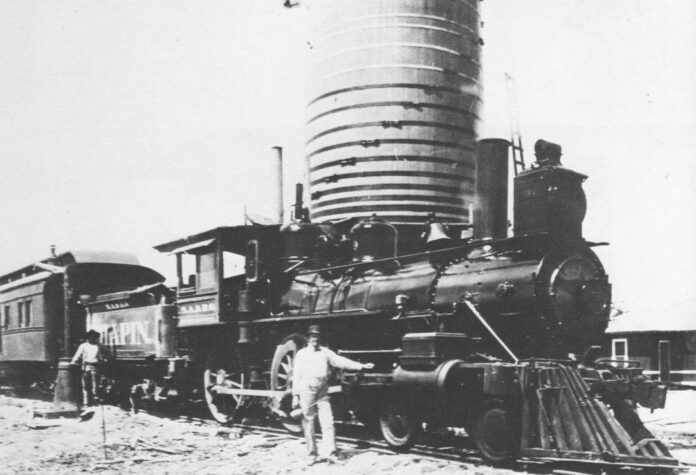

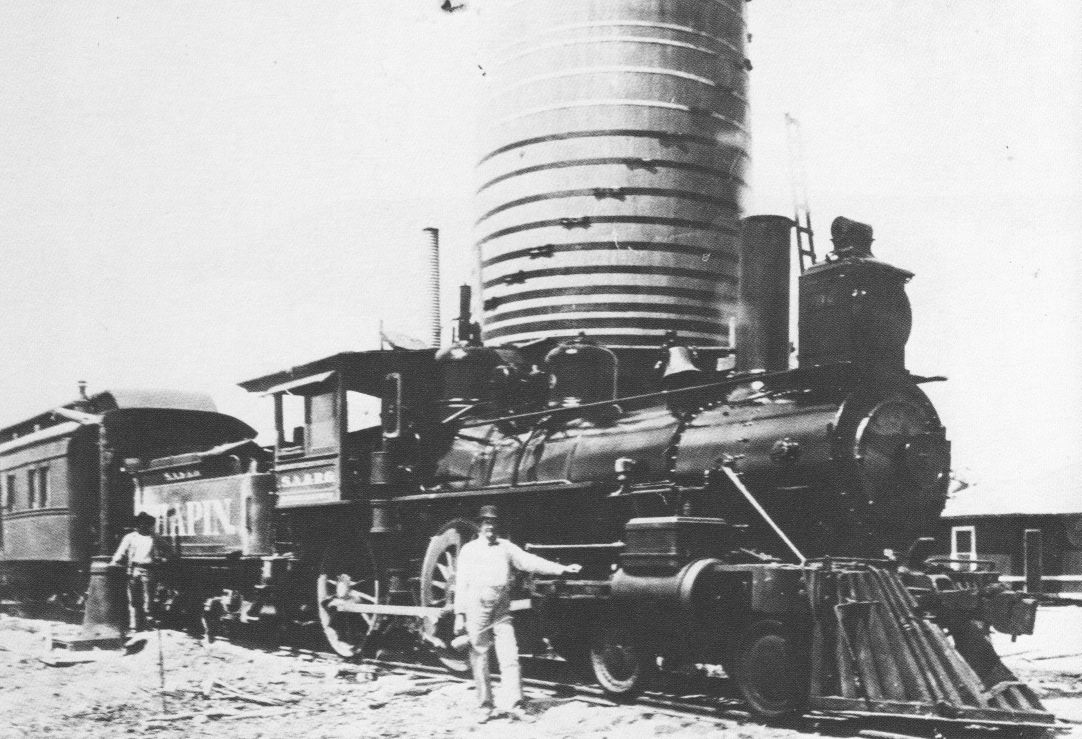

An engine was brought in by the newly renamed San Benito Land and Water Company (SBL&W) and its president Alba Heywood. Its purpose was to power an immense dredge. The canal, which would have 18 miles in its major run and 70 miles of laterals, would be capable of irrigating 45,000 acres. The Houston Post of 7/20/07 reported that in addition to the 15 miles already completed, 23 miles of laterals were finished. By October, the SBL&W purchased an additional 14,700 acres from James A. Browne and his wife for $200,000 or $13.60/acre. By December the company was running ads offering 20,000 acres for sale at $50/acre, 1/3 down and 6 percent interest on the balance due in three annual payments.

The SBL&W had been organized April 11, 1907 as well as the Los Indios Irrigation Company with principals R.L. Batts, Alba and O.W. Heywood and R.E. Brooks. To come later would be the San Benito Irrigation Company with J.C. Miller, Samuel Spear, and F.W. Hall as associates. That Alba Heywood, once part of a comedy vaudeville team with his brothers, had faith in all the new developments was evident when he built a beautiful two story neo-classic brick house facing the San Benito city park. His son, Alba, Jr. would be born in that house December 8, 1908. Heywood also operated a sizable pig farm south of town near what is now South Sam Houston Blvd. When the San Benito Canal’s “frail pump” on the river experienced trouble, Robertson’s neighbor and friend, Lon C. Hill, came to his rescue. Hill and Robertson formed a mutual admiration society.

Sam would later relate: “Lon came to our rescue, and turned water into the resaca, for use of our people. A more selfish person would have knocked the San Benito project and used our breakdown to build his policy. He always has done all possible to help his fellow developers and build up the Rio Grande Valley. Had he sat down like many others, selling only enough land to keep up taxes, he would be a multimillionaire today; but he was a builder, he cleared land, built sugar mills, cotton gins, planted sugarcane and cotton, experimented with all kinds of crops, put thousands of men to work, made it possible for many to build up business and fortunes from his efforts.”