BY NORMAN ROZEFF

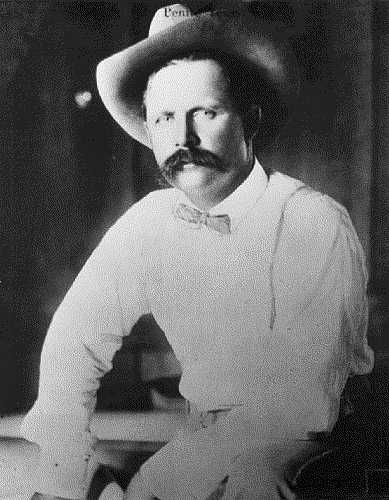

In 1900, at the turn of the century, Sam and brother Frank were general contractors on the Fernwood, Columbia and Gulf RR in Pike County MS for the Enochs family.

In 1901 Robertson got his construction feet wet in Texas by building sections of railroad developer Benjamin Yoakum’s Gulf Coast Lines’ Cleburne to Mexia link of the Trinity and Brazos Valley Railroad. He also constructed a 30-mile logging route for the Orange and Northwest Railroad into Orange, Texas.

It is important to note here Robertson’s construction crew consisted of black and white laborers who had worked with “Mr. Sammy” in Mississippi and Alabama.

Some of this group remained loyal to Sam a lifetime, even following him to France during WW1.

It was in 1901 that a revolution occurred in Texas with the discovery of vast quantities of oil at Spindletop near Beaumont. On August 30, 1901, 61 men, including O. W.

and Alba Heywood, met and appointed a committee to adopt measures for the protection of life and property from fire and explosion in the Spindletop field. Sam began contracting for levee building and road grading in Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas and went flat broke twice.

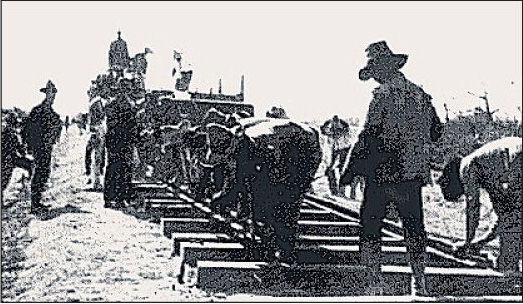

In the early days of Texas oil discoveries around Beaumont, Robertson gained construction experience by throwing up earth dikes around newly-built oil storage tanks. In the fall of 1903 he had been working on the old Nile Valley Canals near Bay City. With the job nearing its completion, he heard about the potential railroad to be built to the Lower Rio Grande Valley (LRGV), went to Corpus Christi, convinced the people at Johnston Brothers of his experience, and was readily hired after promising to lay a mile of track a day.

His powers of persuasion were obviously one of his strengths.

Robertson’s introduction to the LRGV was in November 1903, when, as a subcontractor for the Johnston Brothers, B.F. & P.M, who were contracted to build the St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico Railway line from Robstown to Brownsville, Robertson began grading and laying track. His entity was named the Southern Contracting Company. It would be responsible for grading, track laying, and trestle and bridge construction, not only to Brownsville but later for the railway’s Sam Fordyce branch that would extend from Harlingen west past Mission.

Robertson, a good judge of men, selected Capt. Bill Lewis as president, himself as vicepresident and general manager, and C.S. Hobbs as the firm’s treasurer, trainmaster, and material agent. Lewis Mims was selected to be secretary and superintendent of bridges. Hobbs would go on to become manager of the Brownsville Water District and Mims vice-president and general manager of the large and prosperous Freeport Sulphur Company.

Robertson was to be paid $587 per mile for grading and track laying, and $11.50 per thousand for hauling and framing bridge timber. As a start-up company, he was never able to post the $10,000 performance bond, but, for Robertson’s sake, the Johnston Brothers conveniently overlooked this fact. The truth was that Robertson was nearly always in the red. His was not a firm with a $200,000 line of credit and an A-1 credit rating as some were under the impression.

He was furnished by the Johnstons their 5 spot [a number and spot refers to the numbers placed by logging companies on a shield in the front of their locomotives] locomotive and 75 flatcars with which to work. He was still well short of men, tools, equipment, money, and credit. Still, with the Johnston Brothers contract in hand, he was able to persuade another railroad man to loan him $12,000 to acquire three additional locomotives and tools. These were old engines, ready for the scrap heap.

They would require constant maintenance.

With negligible amenities, his crew of some 300-400 African Americans (in those times they were called negroes and still later, Blacks) and Mexicans had to rough it. Tents were pitched on the flat cars to house and shelter the work crews who often had their families with them. A frequent sight was that of cords extending from the cars to the nearest mesquite trees. On these cords would be hung raw red beef and goat meat left to dry in the sun.

Goat meat was a staple for the Mexicans. Sanitary conditions were generally wretched. Sam himself played the role of doctor to any ailments and accidents.

The supervisory staff lived in windowless boxcars. A loud blast from a locomotive’s steam whistle signaled the end of the work day for teams small and large and for hundreds of mules. The swing trains would then depart to pick up storage yard materials needed for the next day’s work. Robertson was “The law south of the Nueces” and a strict disciplinarian to boot. No booze was allowed in camp, and he even, at times, levied fines on transgressors.

Still, he was considered a great gringo among the hombres. Robertson’s character would stand him in good stead. He had a restless drive to get things done, was an expert borrower, had incredible patience, and was an “incurable optimist”.

He would need these attributes when he learned of the construction’s first major accident on February 17, 1904. It was first thought that a trestle across Santa Gertrudis Creek near Kingsville had given way and caused the work train to wreck. The first seven cars had passed safely across the Santa Gertrudis Bridge before the next nine cars carrying ties, rails, and timbers plunged in a broken tangle to the creek’s bed.

Later it was concluded that spread rails were the culprit causing the accident.

Robertson, then in Corpus Christi, hurried to the scene only to be involved in a wreck himself when, just north of Kingsville, a bad switch threw his locomotive off the tracks. Sam suffered a compound fracture of his right leg and seven broken ribs. For 17 days he would recuperate in Corpus Christi, his leg in a cast and his ribs bandaged. Not content just lying about any longer, he ordered a stretcher and upon being placed on a flatcar went to the construction site and then hobbled around with crutches. Naturally he overdid things, and it was months before he halfway recovered. He then took to riding a white pony that he trained to lie down, so Sam could more easily mount it. Once on site he would limp around with crutches.

This is the second part in an extensive series on Sam Robertson, who helped to create the city of San Benito. See past articles in the series at www.valleystar.com