|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Donald Trump isn’t the first politician who refused to accept defeat, and he isn’t the first to face criminal conviction. He is, of course, the first president in this position — Richard Nixon resigned and was pardoned before formal charges were ever brought against him for his involvement in covering up a burglary of Democratic Party headquarters and other acts against political rivals.

In our nation’s nearly 250-year history, Trump’s case is unprecedented, and before he came along most people probably thought such a thing could never happen. It’s left many people wondering what could happen and what should happen, both historically and legally.

A similar case that took place right here in the Rio Grande Valley three decades ago could offer some guidance to Congress members who wish to resolve the issue and mitigate the obvious damage to our country — if not in Trump’s case, then for any possible reoccurrence.

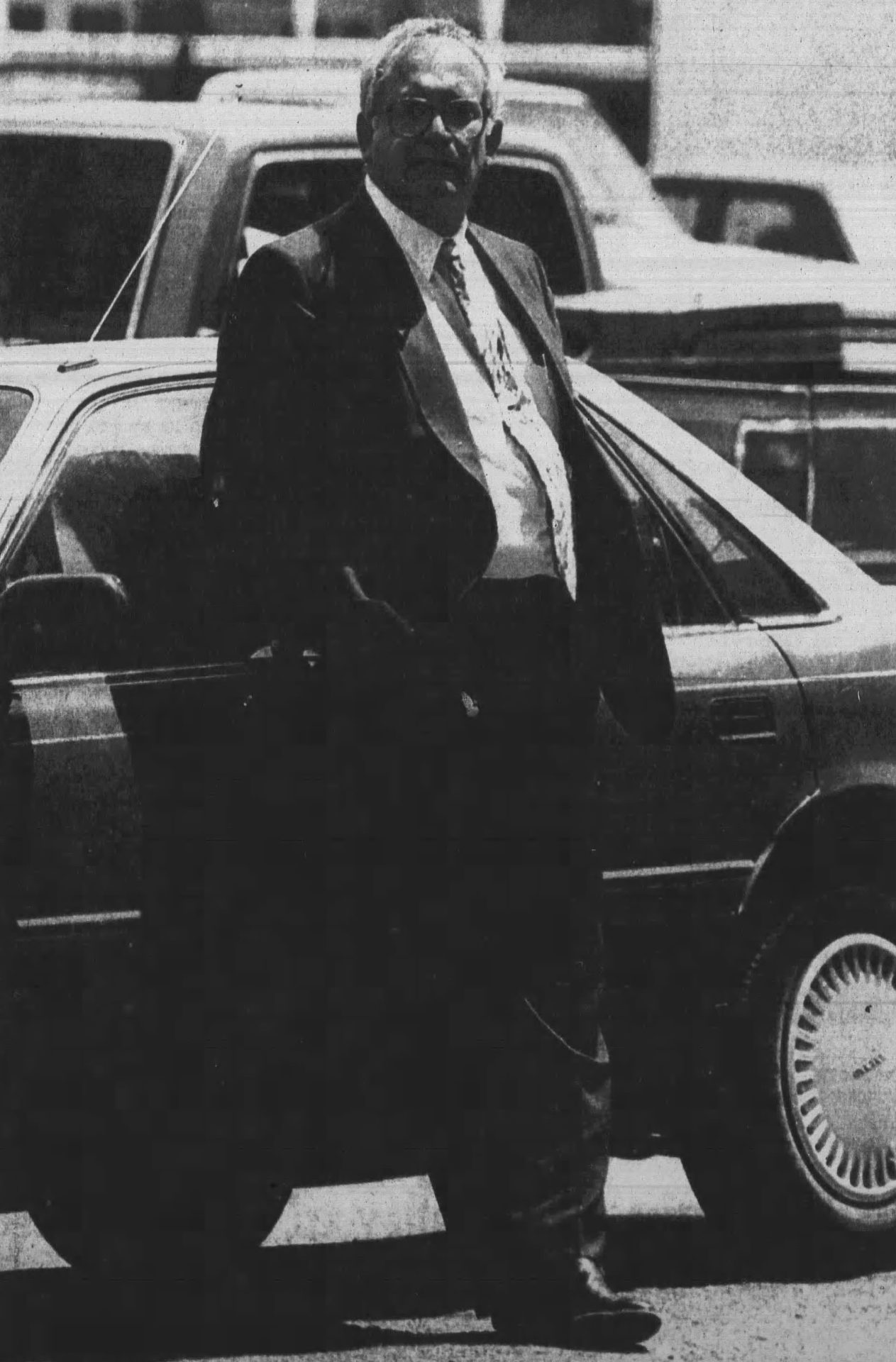

In 1994, Hidalgo County Sheriff Brigido “Brig” Marmolejo was convicted and sentenced to seven years in federal prison for taking bribes including money, a sports car and cabrito to let jailed drug traffickers enjoy conjugal visits. Marmolejo refused to resign from office; he also was running for reelection and declined to remove his name from the ballot so that the Democratic Party could replace him with a more viable candidate. The party sued to have him taken off the ballot, while the Republican Party sued to have him removed from office.

A key ruling in the case came from current state Democratic Party Chairman Gilberto Hinojosa, who at the time was on the 13th Court of Appeals. The former Cameron County district and county judge determined that a conviction is not final until all appeals have been exhausted. Essentially, as long as a conviction could be overturned, a person still has rights that include seeking and holding office.

As a result, Texas lawmakers passed legislation the following year defining conditions under which a person could be removed from office.

To be sure, state and federal cases aren’t always the same, but Marmolejo’s case could provide a glimpse into the kinds of issues that could arise if Trump is convicted of any crimes. His supporters have pointed out that our Constitution does not say that a convicted felon can’t be elected president, although the 14th Amendment disqualifies anyone who has engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the Constitution can’t hold public office. That is among the nearly 100 charges Trump currently faces, although the amendment allows that prohibition to be waived if two-thirds of both chambers of Congress vote to do so.

If convicted, federal courts similarly could rule that Trump could be elected and serve through the appeals process — which likely would extend beyond a second presidential term, and probably Trump’s lifetime. However, the question could inspire Congress members to consider legislation that would help determine when, if ever, a president might be unable to hold the office.

At the very least, it would help inform voters as to whether a vote for Trump might be rendered useless, or whether it remains a valid option.