|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Got plans Sunday night? Now you do.

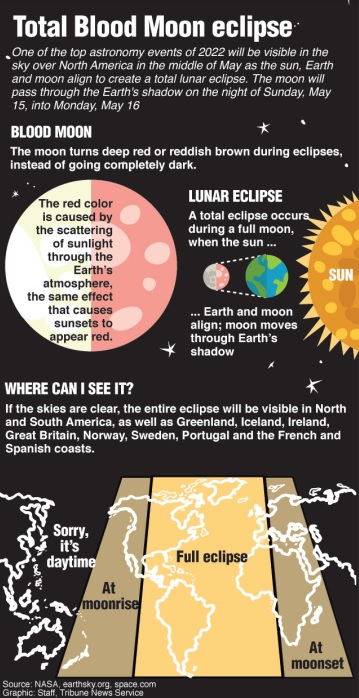

A total lunar eclipse will create what’s referred to as a blood moon this evening, around 11:12 p.m., and you don’t need any hi-tech gear to watch. Just patience.

Here are NASA’s tips on what to expect, how lunar eclipses work, why they’re important, and most importantly, how to capture Sunday’s eclipse on your cellphone.

WHAT TO EXPECT SUNDAY NIGHT

Before getting into Sunday night’s lunar eclipse, here’s two terms you need to know:

>> The penumbra: The moon passes through two distinct parts of Earth’s shadow during a lunar eclipse. The outer part of the cone-shaped shadow is called the penumbra. It’s less dark than the inner part of the shadow, because it’s penetrated by some sunlight.

>> The umbra: The inner part of the shadow is called the umbra. It’s much darker because Earth blocked additional sunlight from entering the umbra.

At 8:32 p.m., the edge of the moon will begin entering the penumbra. During this time, the moon will dim very slightly for the next 56 minutes as it moves deeper into the penumbra.

You may only notice some dim shading (if anything at all) on the moon near the end of this part of the eclipse, because this part of Earth’s shadow is not fully dark.

If you decide to skip this part of the eclipse, you won’t miss much.

At 9:28 p.m., the edge of the moon will begin entering the umbra. As the moon moves into the darker shadow, significant darkening will be noticeable.

According to NASA, during this part of the eclipse, the moon looks as if it has had a bite taken out of it. That “bite” gets bigger and bigger as the moon moves deeper into the shadow.

Viewers in the eastern, central and southwestern U.S. will see the moon as it moves into the umbra, during this part of the eclipse. West Coast viewers should keep their eyes on the eastern horizon for the moon to rise sometime between 7:20 and 8:40 PDT — depending on your location.

At 10:29 p.m., the moon will be completely inside the umbra, marking the beginning of the total lunar eclipse. This is also known as totality.

Viewers in the most northwestern parts of the continental U.S. will see the moon rise as totality is beginning.

At 11:12 p.m., the moment of greatest eclipse, when the moon is halfway through its path across the umbra, occurs.

As the moon moves completely into the umbra, it begins to turn reddish-orange. This happens due to the Earth’s atmosphere. As sunlight passes through it, the small molecules that make up our atmosphere scatter blue light, which is why the sky appears blue.

This leaves behind mostly red light that bends, or refracts, into Earth’s shadow. We can see the red light during an eclipse as it falls onto the moon in Earth’s shadow. This same effect is what gives sunrises and sunsets a reddish-orange color.

A variety of factors affect the appearance of the moon during a total lunar eclipse: clouds, dust, ash, photochemical droplets and organic material in the atmosphere can change how much light is refracted into the umbra.

At 11:54 p.m., the edge of the moon will begin exiting the umbra and moving into the opposite side of the penumbra, reversing the “bite” pattern seen earlier.

At 12:55 a.m., the moon will be completely outside of the umbra and will begin exiting the penumbra until the eclipse officially ends at 1:50 a.m.

TOTAL ECLIPSE OF THE PHOTOGRAPHY

While the eclipse will most likely be documented with professional digital cameras or telescopes, that doesn’t mean you can’t try with your cellphone on hand. Here are some tips for those wanting to capture a photo with their smartphone device.

>> Make sure the image is properly focused. Do not rely on your auto-focus to do it for you. All you have to do is tap the screen and hold your finger on the moon to lock the focus. Then slide your finger up or down to darken or lighten the exposure. On iOS camera apps, tapping an object will center a box around it and show a little sun icon. This is the exposure slider. Drag it down until you see details on the moon image. Android camera apps usually have an exposure setting too, but it might take some hunting around to find it.

>> Take a time-lapse photo series of the scenery as the light dims with the smartphone secured on a tripod or other mounting so that you can watch the eclipse while your camera photographs the scenery.

>> Digital zoom will not work to create a magnified, clear image. There are $20-$40 zoom lens attachments that will give you 12x to 18x. At this magnification, the total solar eclipse will also look much nicer because you will be able to start to see details in the shape of the corona.

>> Consider using the delay timer set at 5 seconds so that once you press the exposure button, the camera waits 5 seconds before taking the shot. That gives your camera/tripod/clamp system plenty of time to settle down and produce vibration-free images.

>> When manually focusing your smartphone on the enlarged moon. make sure that you center the focus spot on the edge of the moon, which will be a sharp edge for the camera to auto-focus on. Also adjust the light sensor spot manually so that it is metering the corona. You may need to move the metering spot around to get the best contrast and image definition.

>> Make sure that for telephoto imagery that you use a tripod because the vibration of your hands will be enough to smear the image and make it very difficult to focus on it.

>> Stop your photography to view the eclipse with your own eyes.

HOW LUNAR ECLIPSES WORKS

When the sun, the moon and Earth align, eclipses can occur. However, lunar eclipses can only occur during the full moon phase. This is when the moon and sun are on opposite sides of Earth.

At that point, while the moon could move into the shadow cast by Earth to result in a lunar eclipse, most of the time the moon’s slightly tilted orbit brings it above or below the shadow of Earth.

An eclipse season is the time period when the moon, Earth and sun are lined up and on the same plane, which allows for the moon to pass through Earth’s shadow. Occurring about every six months, eclipse seasons last about 34 days.

It’s important to note, however, that a lunar eclipse is different from a solar eclipse, which requires special glasses to view and can only be seen for a few short minutes in a limited area as opposed to a total lunar eclipse, which can last over an hour and be seen by anyone on the nighttime side of Earth. If the skies are clear, of course.

In the Rio Grande Valley, skies are expected to be clear Sunday evening into Monday morning.

WHY LUNAR ECLIPSES ARE IMPORTANT

Lunar eclipses have played an important role in understanding Earth and its motions in space.

Rewind to ancient Greece, where Aristotle noted that the shadows on the moon during lunar eclipses were round, regardless of where an observer saw them. This led to his realization that only if Earth were a spheroid would its shadows be round.

That revelation was held by him and others many centuries before the first ships sailed around the world.

The phenomenon precession is when the Earth wobbles on its axis, like a spinning top that’s about to fall over. Over the course of 26,000 years, Earth completes one wobble, or precession cycle.

This discovery was made by Greek astronomer Hipparchus by comparing the position of stars relative to the sun during a lunar eclipse to those recorded hundreds of years earlier. Because of a lunar eclipse, Hipparchus was allowed to see the stars and know exactly where the sun was for comparison: directly opposite the moon.

This is important because if the Earth didn’t wobble, the stars would appear to be in the same place they were hundreds of years earlier. By seeing that the stars’ positions had indeed moved, Hipparchus knew that the Earth must wobble on its axis.

Now fast forward to the present, where modern-day astronomers have used ancient eclipse records and compared them with computer simulations. By doing so, the comparisons helped scientists determine the rate at which Earth’s rotation is slowing.

Editor’s note. Information has been sourced from NASA and the California Institute of Technology.