HARLINGEN — The unassuming lobby and front office space of Casa de Proyecto Libertad belie the size of the nondescript building here off 1st Street, which Rogelio Nuñez refers to as his “warehouse of files.”

For years, most of the building’s rooms have sat unoccupied, but not empty. Filing cabinets line the walls and stacks of folders and books cover desks, drawers pushed open by overflowing paperwork — each document telling a story; each office once occupied by attorneys and paralegals who came to the Rio Grande Valley to work on immigration cases.

A former doctoral student in sociology and university professor, Nuñez, 66, has served as the nonprofit’s director since 1999, dedicating his career outside of academia to helping migrants navigate the nation’s ever-changing immigration policy landscape.

While the Valley remains a transitory place for migrants, an entryway into the United States and one of the many stops on their journey north, the San Benito native works with those who decide to plant roots here.

The Valley, Nuñez said, “has always been a detention zone” for both those who decide to leave and those who stay.

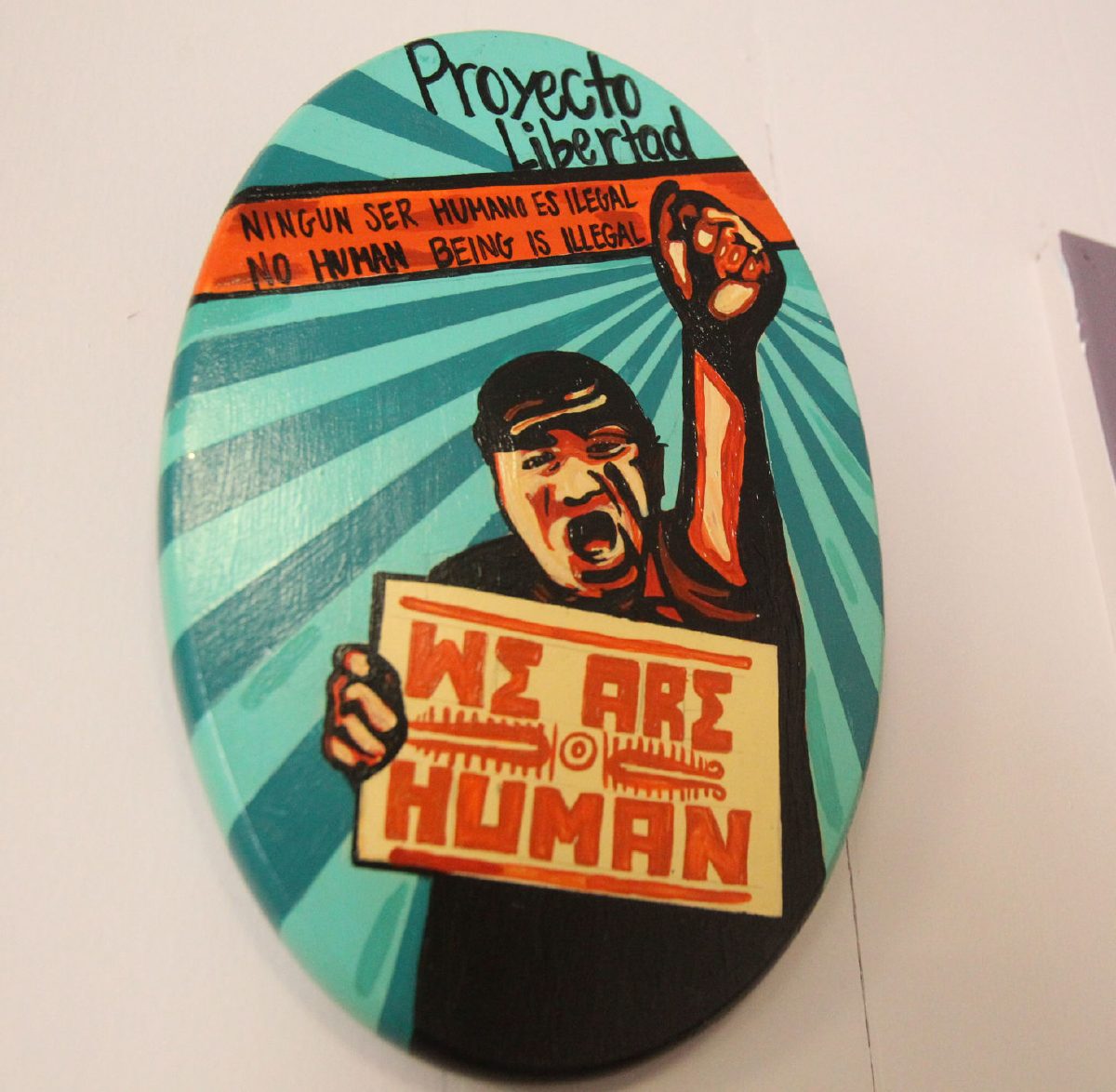

Formed in July 1981, Proyecto Libertad first provided legal defense to Central Americans detained at the Port Isabel Service Processing Center, the detention facility that has captured the nation’s attention nearly four decades later.

The center is one of the sites currently holding migrant parents separated from their young children after they were apprehended crossing the border illegally, driven north by the legacies of Central America’s civil wars of the 1980s which have given root to the region’s high rates of poverty and violence.

In 2003, the nonprofit shifted its focus to providing legal services to immigrants who are not in detention, as well as supporting survivors of domestic abuse on this side of the border.

Specifically, Nuñez helps undocumented women and their children, who are mostly from Mexico, apply for permanent residency and citizenship under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and the U nonimmigrant status (U visa), among other laws.

U visas, of which the federal government allocates only 10,000 annually, are for victims of certain crimes who endured mental or physical abuse. According to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, those who qualify for U visas can aid in the investigation or prosecution of criminal activity.

By December, three months into the fiscal year, the available visas run out, Nuñez said, “which only tells you there are too many violent cases.”

A woman and her two elementary school-aged children stopped by Proyecto Libertad’s office Friday afternoon to inquire in Spanish about the steps needed to apply for U.S. citizenship.

“ What language does your mother scold you in?” Nuñez asked her daughter, who shly answered in fluent English that her mother uses Spanish. “And what language do you talk back to her in?” he followed up, to which she again responded Spanish.

“You need to use English with your mother; you need to read to her in English,” Nuñez told her. “She needs to learn English.”

Nuñez explained to the mother, a lawful permanent resident who lives in Mercedes, that she needs to know sufficient English to be able to pass the citizenship exam. As the mother to two U.S.-born children, obtaining citizenship will shield her from deportation, which becomes a possibility if green card holders are convicted of certain crimes.

Having already seen the Donald Trump administration put an end to Temporary Protected Status for Hondurans, Salvadorans and Haitians, Nuñez is well aware that other programs protecting immigrants from deportation could come to an end.

“Clients are scared … It eats me up in a sense of what best can I do from the time I get here to the time that I leave,” he said, explaining that in the months leading up to the 2016 presidential election he began giving clients his cell phone number to ensure they could reach him. With a staff of four, counting himself, and a mounting caseload, Nuñez is constantly busy, facing a sobering reality.

“This is not going to go away,” he said of the administration’s immigration policies. “Every president since 1848 has had concerns for national security … (for) the security of this border.”

That year marks the end of the Mexican-American War, the negotiation of the current boundary between the countries and the beginning of securing the border, what “has always been a major piece of this country,” Nuñez said.

VAWA, which found itself in jeopardy of nonrenewal in 2012, is up for reauthorization by Congress this year, and U visas will be reviewed by the Federal Sunset Commission in the coming years.

Though Nuñez technically retired in 2014 to save the nonprofit money since grants have become harder to come by for organizations that provide direct legal services, he’s continuing this work until “the day I die.”

His advice to other organizations doing similar work — such as the San Antonio-based legal services group RAICES, which raised $20 million in just a few weeks to post bonds for detained women separated from their children — is to develop long-term plans that include a mix of legal services with advocacy in order to protect the legal structures in place.