|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Millions of Americans have seen a loved one diagnosed with cancer or been diagnosed with the disease themselves. While important gains have been made in the war on cancer thanks to screening improvements and healthier lifestyles, the numbers are still staggering. Nearly 2 million people in the U.S. will be diagnosed and more than 600,000 will die from cancer this year. The financial toll is also significant: more than $200 billion will be spent on the disease — primarily in treating late-stage cancers.

The Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute recently examined these issues, exploring the gaps in cancer detection, the promise of innovation and needed policy change to help control cancer’s burden and lower treatment costs in Texas.

When cancer is detected earlier, treatment is less expensive and survival rates are much higher. One study found that the average first-year cost of Stage I liver cancer treatment was $73,816, while the average first-year cost of Stage IV liver cancer was $155,515. The five-year survival rates for ovarian cancer and pancreatic cancer are 93% and 44%, respectively, when the cancer is diagnosed early. After the cancer has spread, the survival rates plummet to 31% and 3%, respectively.

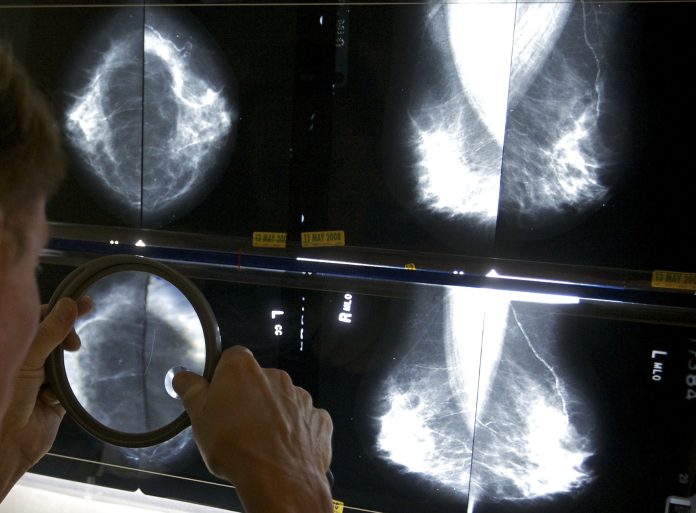

Unfortunately, recommended screenings exist only for breast, prostate, cervical, lung and colorectal cancer. Well over half of the people who die of cancer in the U.S. each year die from a cancer that has no commonly available screening. Many cancers are not diagnosed until patients exhibit symptoms. By then, outcomes are poorer and treatment costs are higher. Clearly, the need exists for screening that can detect multiple cancer types, is easy to administer and can detect cancer at earlier stages, when patients are asymptomatic. Multi-cancer early detection (MCED) is an emerging innovation that checks all of those boxes. MCED works by analyzing a blood draw for biological signals that suggest the presence of cancer. Remarkably, MCED can often identify the organ from which the concerning signals originate, allowing targeted care.

Our analysis, “The Potential for Multi-Cancer Early Detection Testing to Save Lives and Deliver Cost Savings,” finds that the potential positive ramifications of MCED adoption are extraordinary. MCED could slash cancer mortality by 25% or more, providing unquantifiable benefit to millions of Americans, their families and their communities. Further, earlier cancer detection could reduce annual treatment costs by $26 billion, one study estimates. That does not include billions of dollars in cancer-related lost productivity that MCED could “save.” Some may caution against MCED’s potential, pointing to problems arising from false positives and false negatives. Any cancer screening can generate erroneous results, but in terms of performance, MCED tests compare favorably to the recommended screenings for the five cancer types listed above — screenings that are credited for reducing cancer mortality. Moreover, MCED performs well in detecting the dozen cancer types that together account for about two-thirds of annual cancer deaths in the U.S.

A bill before Congress, the Nancy Gardner Sewell Medicare Multi-Cancer Early Detection Screening Coverage Act, would create a pathway to allow Medicare to cover MCED tests that have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Led by U.S. Rep. Jodey Arrington of Lubbock, the bill has bipartisan majority support in Congress, including 25 other Texas members.

The bill’s passage would not only save patients and the health care system billions of dollars, but would also benefit millions of Americans who will receive a cancer diagnosis by enabling that diagnosis and treatment sooner.

Tom Wolfe is a senior policy analyst at the Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute, based in Austin. His white paper on MCED can be found on TCCRI’s website: txccri.org