One of the highlights of my long legal career was the honor of serving as César Chavez’ lawyer for 18 years and for the United Farm Workers, AFL-CIO here in Texas during its organizing campaigns. I also had the opportunity of marching with César on twin 60-mile marches in South Texas, from Brownsville and Rio GrandeCity that met in San Juan, to raise farm labor wages.

At this time of the year, when we commemorate César’s life with a holiday in many parts of the country, I always feel compelled to write a bit about his life and impact. I’ve done so for about 25 years now. This year, I want to focus on what I learned personally from him in the hope that my reflections might be helpful for others involved in social change efforts.

César inspired many and changed their lives. He inspired me to move from Michigan to the Rio Grande Valley and work there. I learned much from him about the movement and how to be a lawyer who works with the community.

So, here my takeaways for your consideration, as they occur to me.

Love your family, and love everyone else and everyone else’s family.

Practice nonviolence as a way of life, not a movement tactic. Non-violence does not accept non-action, and may require fierce action. Farm workers were brutally beaten by police and goons during organizing campaigns, and three were killed. As John Lewis put it, you must look the person in the eye who is brutalizing you with the compassion of non-violence that understands your assailant is as much of a victim as the person being beaten. Love the person who is the brutalize, but struggle against the system the brute represents.

Keep focused on the goal and do not get distracted. There once was an impetus in the Chicano movement, as it was called then, to recognize César as its paramount national leader. He declined, saying his work was for the farm labor movement, and to that end, he would remain exclusively dedicated.

Develop a deep spirituality with the faith that justice will prevail no matter how ferocious, ruthless or sophisticated the opposing tactics are against the movement.

Cesar never got beyond eighth grade because he had to join the migrant stream to help support his family, but that never stopped him from reading all the time. He always traveled with books of all kinds, and often read after everyone went to bed. Read, read, read.

Be personally disciplined, part of which is fasting. Cesar, of course had three major weeks long fasts, one being to keep the movement in a mode of non-violence. He never suggested that others do that; but he was clear that weekly, regular fasting for a day or two was important.

Don’t be materialistic. Like other UFW organizers at the time, César earned $5 per week, plus modest living expenses. Seeking a high salary, living in a nice part of town, driving an elegant car, for example, lead to distraction and self-centeredness.

As far as any form of a movement for justice (civil rights, economic, environmental), dignity is what’s at stake. From that, all justice flows.

We must live and breathe our cause; it is not a 40-hour-a-week endeavor. And we must work with the community and not just for it. As César often said, “If the poor are not involved, change will never come.” We don’t organize for, but with.

César may not be among us any longer, but his spirit is. He gave us an example of an unrelenting fierceness for justice, bringing together our common suffering and love for each other.

He framed it once this way: “The truest act of valor is to devote ourselves to others in the non-violent struggle for justice.”

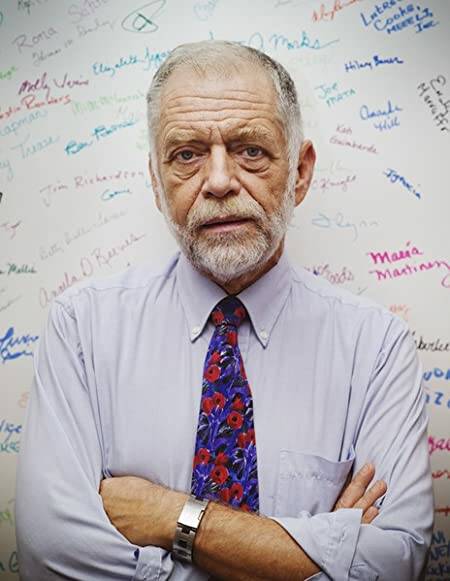

James C. Harrington is the retired founder of the Texas Civil Rights Project in Austin.