U.S. Border Patrol agents are sending some migrant children with special needs who are seeking asylum with their parents back to Mexico under a federal public health code. One volunteer group in Reynosa is helping some families, including a child in need of a special mobility chair.

(Courtesy Photo)

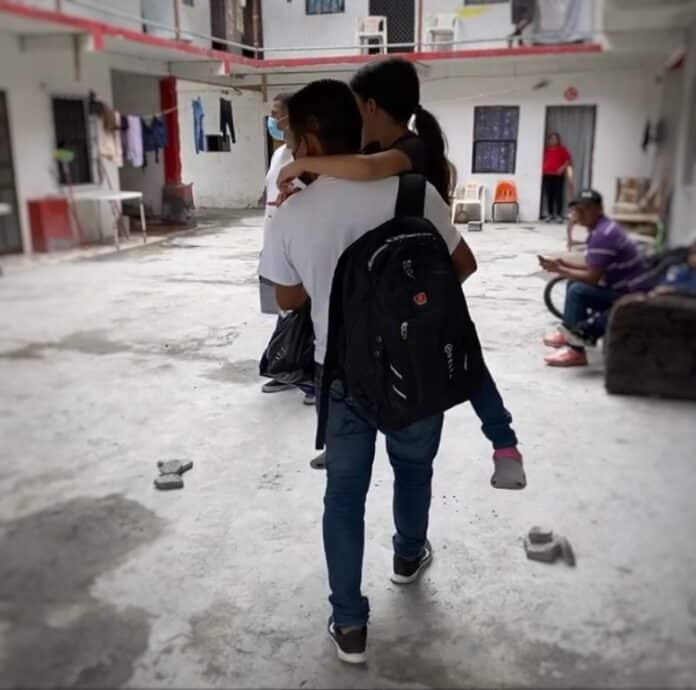

Luis Alberto Lobo Sanchez carried his 9-year-old daughter, Dayana, most of the way from Honduras to Mexico. Dayana struggles with spina bifida, strabismus, convulsions, and urinary reflux, a condition that requires a catheter and diapers. Lobo Sanchez and his wife struggled as they watched her health decline.

“As parents, we didn’t want to see her in a coffin,” her dad said. The family didn’t have enough money to make the trip to the border together. “We made the drastic decision to separate her from her sister.”

Dayana left her home, her mother and 1-year-old sister behind under the illusion that they were in a slower bus trailing behind.

Lobo Sanchez instructed his daughter not to speak during the journey to avoid having her accent give them away to those seeking to kidnap and extort immigrants. He rationed their money but they fell victim to theft and abuse along the way.

At one point, Lobo Sanchez was beaten by thieves. Other times he struggled with the weight of carrying his daughter and the emotional weight of keeping her spirits high when she cried for her mother. When the money ran short, he gave up food to make sure his daughter didn’t go hungry.

The pair arrived at the border and tried claiming asylum through the ports of entry on two occasions, but they were denied the opportunity to present their request. (The U.S. is still enforcing a public health code known as Title 42, which largely prohibits entry to migrants to avoid spreading COVID-19.)

“I’m very conscious of the laws. I’m a person who reads a lot, but these special circumstances force you to make these kinds of decisions,” Lobo Sanchez said.

Dayana and her dad crossed the river on an inflatable raft with other migrants who paid a smuggler. They walked a part of the way after they stepped on U.S. soil. Dayana’s leg braces, which she’s outgrown, caused her ankles to bleed.

When agents found them, they took them in for processing which includes fingerprints and other biographical information like age. Some families with children younger than 6 are released into the U.S. through McAllen.

“Why did you come?” an agent asked Lobo Sanchez. “I came because of my daughter’s condition,” he said. He had documents including brain scans of Dayana’s medical condition.

“Is that cured over here?,” Lobo Sanchez said the agent asked next. The father told the agent he hoped his daughter would receive better care in the United States.

“The agent said, ‘Unfortunately, we won’t be able to help you’ and he turned around and gave us his back,” Lobo Sanchez said. He didn’t get a chance to show the medical documents. That’s when he realized they would be sent back to Mexico.

A statement from U.S. Customs and Border Protection was requested and remains pending.

(Courtesy Photo)

They arrived in Reynosa on Thursday without a place to go, but they ended up at a city park where other migrants are staying in tents, about a block away from the international bridge. That night, Dayana slept on a blanket spread across the grass of the plaza, her ankles still bright red from the tight braces that rubbed against them.

The next day would be spent at a hotel paid for by the Sidewalk School, a nonprofit organization helping migrants with food and shelter. Felicia Rangel-Samponaro is a cofounder who welcomed the father and daughter when they arrived.

“When we got to the hotel, he was still carrying her,” Rangel-Samponaro noted.

The nonprofit is covering the rent for 20 families who were expelled from the United States to Reynosa. Some migrants remain at the plaza, including a different father and daughter who had an arm with a visible deformation from a possible infection.

Rangel-Samponaro sent money to help cover medical expenses for the child’s arm, including medication that was wrapped in a bag. A few hours later, someone stole the bag.

Expenses are adding up for the nonprofit, including a new goal to purchase a mobility chair for Dayana. They project it will cost about $3,000. Donations are collected on their website at SidewalkSchool.org.

Rangel-Samponaro said they will raise the money, but is concerned about future vulnerable migrants. Advocates like her believe agents should not have the authority to make those decisions alone.

“I don’t think that should be within their power. I don’t think they should be able to decide who gets to stay and who gets to go. Because they’re expelling children with disabilities,” Rangel-Samponaro said.

An attorney, who did not provide a comment, will be taking up Dayana’s case.

A different immigration lawyer, Charlene D’Cruz, has successfully helped between 20 and 30 people get through the border in spite of the Department of Health and Human Services order issued in October 2020, which allows exceptions.

“This Order does not apply to persons whom customs officers determine, with approval from a supervisor, should be excepted based on the totality of the circumstances, including consideration of significant law enforcement, officer and public safety, humanitarian, and public health interests,” the order reads.

It also directed DHS to consult with CDC on these exceptions to help ensure consistency with the guidance.

D’Cruz said the humanitarian exceptions are inconsistently applied in her experience.

“It’s not just open to anybody coming up to the border. It has to be through attorneys. So, that’s how I’ve gotten people through,” D’Cruz said. “But the vast majority of people are still being kicked out. So, the question becomes, if you have this exception to Title 42, why are you not exercising it when people are crossing irregularly and, number two, when people are presenting at the border?” She concluded, “So, it’s a very ad hoc, a very inconsistent system.”

D’Cruz said access to exceptions is a historical problem through Democratic and Republican presidential administrations. Lawsuits are used to challenge policies like Title 42 and the Migrant Protection Protocols, recently shut down, to improve access to asylum by vulnerable groups.

Lobo Sanchez is hoping his attorney will be successful; but, in the meantime, Dayana is starting to notice her mother’s absence and is asking questions of her own.

“She’s starting to analyze the situation and asks, ‘where are we?’ Sometimes I don’t know what to say anymore,” Lobo Sanchez said.