|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As the spring sunshine continues to scorch, the combined storage at the two international reservoirs that supply the bulk of the Rio Grande Valley’s freshwater has done something it hasn’t done in decades — fallen below 20%.

“Everything that we had forecast is happening. We’re dwindling in our supply. There’s no indication that Mexico will do anything for us,” Sonny Hinojosa, general manager for Hidalgo County Irrigation District No. 2, said Tuesday.

“It’s pretty bleak,” he said.

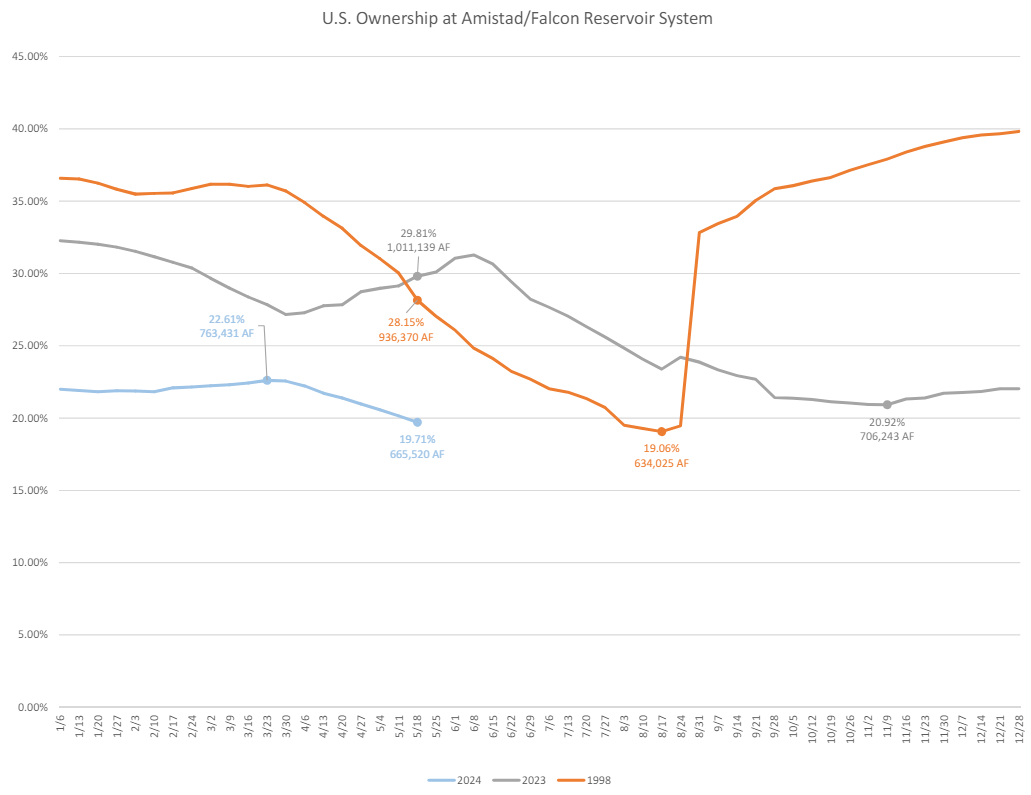

Together, the United States’ share of water stored at the Falcon and Amistad international reservoirs stood at just 19.7% total conservation capacity as of May 18, according to data published by the International Boundary and Water Commission, or IBWC.

The IBWC publishes the report every Saturday using data that are about a week old.

That’s how much time it takes for the commission — which oversees a binational 1944 water sharing treaty between the U.S. and Mexico — to figure out how much of that water belongs to the Valley.

That May 18 figure is a worrying number for Hinojosa. It represents the second-lowest volume of American water in nearly 30 years.

The last time the levels fell below 20% was in August 1998, according to Jim Darling, former McAllen mayor and president of the Region M Water Planning Group.

It’s been a tough year for Valley water.

The binational treaty obligates Mexico to deliver some 1.75 million acre-feet of water to the U.S. in five-year cycles.

But well into the fourth year of the current cycle, Mexico has delivered only about 384,000 acre feet, or about one year’s worth, of water. That has, in turn, caused the two reservoirs to hover at dangerously low levels for months.

Each week the reservoirs continue to plummet at a rate of about four-tenths of a percent per week, Hinojosa said.

Given that reality, the irrigation district manager said he fully expects this week’s upcoming IBWC report to show that American shares of water have plummeted to new, historic lows.

“If we continue on that same track of four-tenths a week, we should be at 19.3%” for the week ending May 25, Hinojosa said.

“And then by this Saturday, maybe 18.9% — which would break our all-time low record,” he added.

Should reservoir levels fall below 19% this coming week, that rock-bottom level would come nearly three months sooner in the calendar year than the last time the reservoirs were so low, Darling said.

“In 1998, if you look at the water (levels), they started out with a lot. And it really went down in August. So, we’re close (now) to where they were in August (1998),” Darling said.

“And we still have two-and-a-half months to go before we hit that. So, it can be pretty serious,” he added.

Making things worse, medium-range climate models are calling for another exceptionally hot summer — one that is expected to come on the heels of an equally “off the charts” spring, according to the National Weather Service at Brownsville.

Thus far, temperatures in 2024 have been running an average of 2 to 3.5 degrees hotter than normal, according to NWS Meteorologist Barry Goldsmith.

On Monday, Goldsmith released his quarterly climate outlook, which includes precipitation, temperature and other climate model predictions for the next three months.

“The impact from the heat and lack of rainfall, combined with record low reservoir levels at Amistad and Falcon… is putting unprecedented stress on agricultural and an increasing number of municipal water supplies,” Goldsmith stated.

Goldsmith warned that water conservation measures will become even more critical in the coming months, lest “periodic shutoffs become a reality.”

Asked if Valley residents could see a day later this summer where nothing comes out of their taps, Hinojosa said it could happen.

“There’s always a possibility,” he said.

When asked what would happen then, the career water man scoffed before answering soberly.

“That’s what we have been trying to ask and no one has an answer. It’s a strong possibility … that that happens,” Hinojosa said.

“We’ve been raising and sounding the alarm … the last two years that we’re heading in this direction and it seems like we still can’t get the cities engaged in how serious this is,” he added with a note of frustration.

Local leaders can no longer pin their hopes on Mexico making good on their treaty obligations.

When a tropical weather system dumped more than 2 million acre feet of water into Mexican reservoirs in 2022, the country still failed to release water to the U.S.

“We used to hope for, like, a benevolent hurricane that went into Mexico … but if we get one and they continue their position of not giving us any water, it doesn’t help us,” Darling said.

Further, despite the still-falling water levels at Falcon and Amistad, this year’s crisis may not be an immediate lack of water, but an inability to deliver it.

As Darling explained, even if it doesn’t rain, and even if Mexico continues to not deliver water, there’s still enough stored in the two reservoirs to supply Valley cities — at least for one more year.

“We own the bottom of the reservoir, so we still have a whole year’s supply for cities,” Darling said.

However, it takes water to move water.

The Valley relies upon a vast spider web of irrigation canals to deliver that water from the Rio Grande to municipal systems.

“Without agriculture, it’s a very inefficient river,” Darling said.

For Hinojosa, both local leaders and Valley residents need to take a hard look at what’s happening.

“We need the cities engaged. We need stricter measures. Because this is extremely serious,” Hinojosa said.

“People aren’t taking this as serious as they should be.”

RELATED READING:

Valley will continue to experience intense heat through at least mid-July