|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Jack McElroy

A century ago, a remarkable editor blew the lid off the Teapot Dome affair. He would go on to lead the Lower Rio Grande Valley newspapers.

The man was Carl Magee, and his exposure of the corruption scandal — the biggest in the nation’s history up to that point — was just one of his many claims to fame.

In fact, he arrived in the Valley in 1937, soon after inventing the parking meter and installing the first ones in Oklahoma City.

Magee’s stint as editor-in-chief of The Brownsville Herald, Valley Morning Star in Harlingen and The Monitor in McAllen came late in his astonishing career, as he was grieving the death of his beloved wife, Grace.

He and Grace were Iowans who had met at the state’s teaching college in the 1890s. Magee soon became a school superintendent, at age 23.

Growing bored as an educator, he studied law, and the family moved to Tulsa, where he hung out his shingle as a lawyer.

As oil strikes turned Tulsa into the “Oil Capital of the World,” Magee succeeded in business and the legal profession. He also led an anti-corruption movement that got the mayor and police chief indicted, and he championed a campaign to build the water system that still supplies Tulsa to this day.

But Grace developed tuberculosis, so the family moved to Albuquerque, where the desert climate offered the best chance for recovery.

There Magee pursued a long-held dream of publishing a “truth-telling” newspaper.

He bought the Albuquerque Journal and began attacking New Mexico’s rampant corruption. That threw him into conflict with Albert Fall, the U.S. senator who headed the Republican political ring.

Their feud continued after Fall became U.S. secretary of the interior. In that role, he cut secret deals to allow two oil tycoons to drill in the Navy’s Teapot Dome and Elk Hills petroleum reserves.

As the Journal raised questions about the arrangements, Fall lashed out, forcing Magee to sell the paper. The editor responded by launching a new newspaper, which would evolve into the Pulitzer Prize-winning Albuquerque Tribune.

Eventually, Magee was called to Washington to share what he had learned. His testimony before the Senate Public Lands Committee in late 1923 and early 1924 turned a humdrum political controversy into a scandal that rocked America.

Investigators would uncover some $400,000 in payments the oil millionaires made to the interior secretary, equivalent to about $6.5 million today. Fall was convicted of bribery and sent to prison.

That wasn’t the end of Magee’s story, though.

A vindictive Republican judge tried him on trumped-up charges of libel and contempt, and Magee escaped imprisonment thanks only to gubernatorial pardons.

Later that same judge met Magee in a hotel lobby and attacked him. Sprawled on the floor, the editor grabbed a gun and shot his assailant in the arm. The gunfire also killed a bystander. Magee was charged with murder but acquitted.

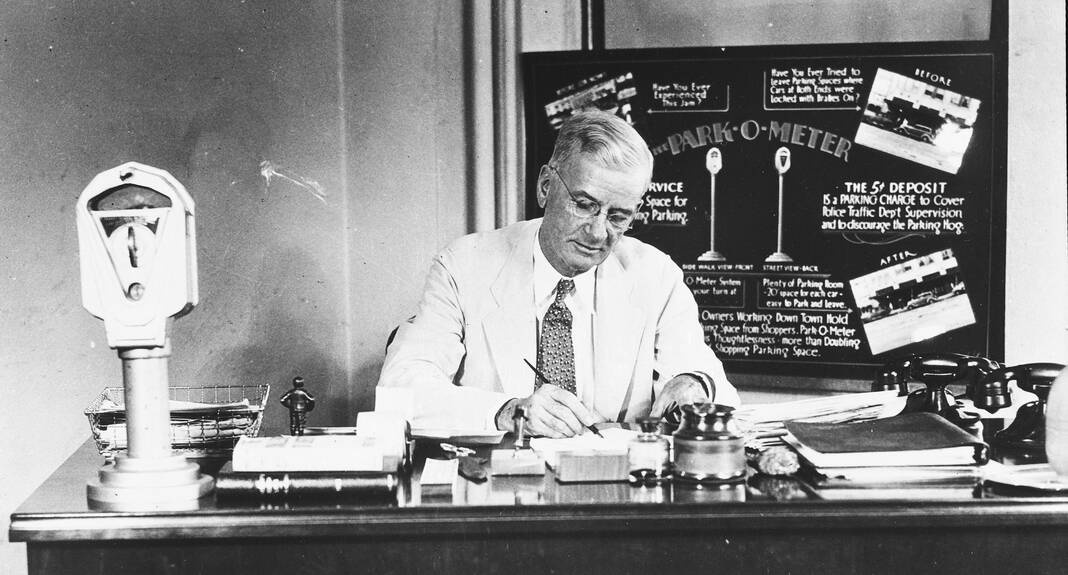

Eventually, Magee sold his paper and became editor of the Oklahoma News. In that role, he was recruited by the Chamber of Commerce to try to solve Oklahoma City’s downtown parking congestion.

That’s when he came up with the idea for the parking meter. Millions of his Park-O-Meters would be sold around the world.

In 1936, Grace Magee died. Magee was heartbroken, and he decided to leave Oklahoma.

Hubert R. Hudson, a former Oklahoma City businessman, had purchased a bank in Brownsville and now was arranging to buy the Lower Rio Grande Valley’s daily newspapers. He recruited Magee to help launch the Valley Publishing Company, with Magee as chief editor of the three papers.

Magee took up residence in Harlingen’s Reese-Wil-Mond Hotel, and started crusading against political corruption and for press freedom. His targets included a Texas Ranger who drew a gun on a newspaper photographer and a Cameron County sheriff who misused office fees.

But Magee’s major focus was the citrus market. In more than 100 of his famous “Turning on the Light” columns, he tried to help the region manage the uncertainties that plagued the industry based on a perishable commodity. He had little success.

In 1938, a series of events disheartened Magee. A strike forced the shutdown of the Brownsville newspaper plant. A new investor in the McAllen paper moved “Turning on the Light” off the front page. A contentious election prompted a vicious scandal sheet aimed at the editor.

Magee, meanwhile, had recovered from his despair over losing his wife. He decided to move on.

Early the following year, at the age of 66, Magee returned to Oklahoma City, where he spent the rest of his life doing volunteer work, including heading Oklahoma’s War Chest, which raised money for the Red Cross, USO and similar programs to benefit GIs during World War II.

Carl Magee died in 1946. But the three newspapers of the Lower Rio Grande Valley have continued the collaboration he helped inaugurate.

Jack McElroy’s biography of Carl Magee, “Citizen Carl: The Editor Who Cracked Teapot Dome, Shot a Judge and Invented the Parking Meter,” was published recently by the University of New Mexico Press.