|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

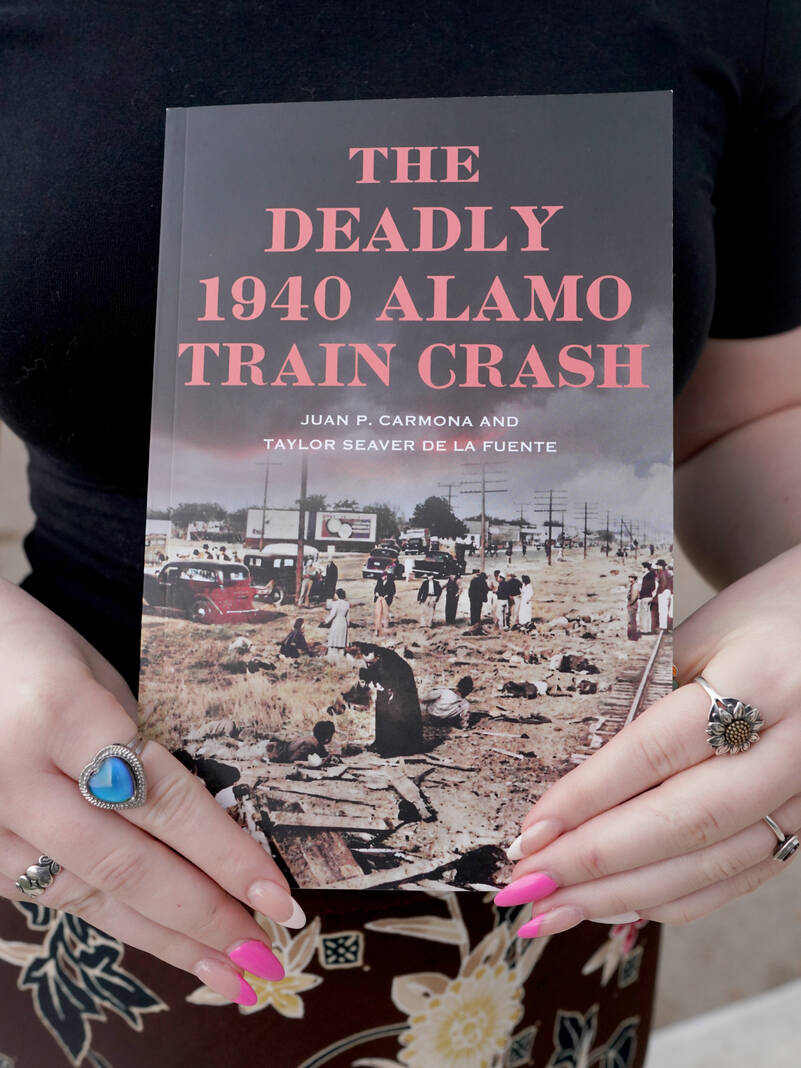

Nearly 84 years after the Alamo train crash, Juan Carmona and Taylor Seaver De La Fuente stood at the exact place of the devastating accident with their new book, “The Deadly 1940 Alamo Train Crash,” which was written to preserve that deadly moment in Valley history and to remind people of the struggles of farmworkers.

Carmona is a Donna High School social studies teacher and De La Fuente is a UTRGV graduate student. They said the idea for the book initially started from a class project that discussed the event in a podcast.

Both being the children of farmworkers who have a passion for Valley history, they decided to put their research into the book.

Published on Monday, Carmona said the book is the culmination of nearly three years of research with De La Fuente. The book dives into the details of the 1940 Alamo train crash, the aftermath and how it impacted the families involved.

“Our history is not documented, a lot of it isn’t,” Carmona said. “It’s important to preserve it because it’s a story of farmer workers … and just the fact that they were just going out to feed the nation really, and they passed away and it had greater impacts on their families and those that were left behind.”

On March 14, 1940, a Missouri Pacific Rail train heading west along Highway 83 from Donna to Alamo struck a truck carrying around 40 migrant farmworkers who were turning north from the highway onto Tower Road.

The crash resulted in the deaths of around 29 farmworkers, which caused unimaginable generational trauma for the families who were impacted.

Describing what happened on the morning of the crash at the exact location on Thursday, Carmona said there is speculation on certain details such as if the train blew its whistle or if the truck had a broken window covered with cardboard.

“The train hit it right on the cab dragging the truck 750 yards that way and scattering people all along these tracks,” he said.

With people scattered over the place, body parts were also spread among the disastrous crash. Carmona said a chilling piece of information they found in research was that city workers and some women were sent to clean up and collect what was left.

“They used costales,” he said. “ A costale is what they picked the fruits and put in. So literally the thing they worked with was what they were put into and I had to take a moment. It hit me when they said that.”

Carmona said finding the names and information on the 29 killed was one of the hardest parts of writing the book.

“It took us like a whole summer to figure out who actually passed away and because the newspapers had different names, misspelled names … it was a mess,” he said. “We had to go to the cemetery. We had to look at the death records to actually get an accurate list.”

Suing the railroad company for around $650,000, Carmona said people ended up getting $14,000 in total which is less than $1,000 per person to cover medical and funeral expenses.

“They were just completely forgotten but the accident remained in the community’s minds,” he said. “Farmworkers go unnoticed all the time, so not to tell the story of the 29 of them passing away is almost a disservice.”

De La Fuente said she thinks the Alamo train crash and other stories in the Valley are not forgotten but are not paid attention to by academics, museums and archives.

“It’s community history and it’s our responsibility to bring our family stories out into the public,” she said.

Writing an afterword in the book that includes photos of her grandparents, De La Fuente said she hopes people can see their own family as academic sources and that their stories are just as important in history.

“Their story deserves to be told and the people who’ve passed away … it’s not just one person affected, its generations but it’s also our responsibility to heal that trauma,” she said. “So it really starts with acknowledging what happened, acknowledging the suffering, acknowledging everything. That acknowledgement really does lead to healing. So that’s really why we’re so passionate about it.”

She added that some people do not know or understand how important Valley history is to the region itself and how it played a role in national and international history.

“We need to be preserving and talking about that, we shouldn’t be going to school and not hearing our own history,” Carmona said. “This is just as important as anything else.”

Carmona also hopes the book inspires families to share their own stories as a way of oral history.

“Once kids are like high school, college age, they start to hear stories that they hadn’t heard because they were kids and the parents kept them from it,” he said. “I’m hoping that this will open up conversations within family to share their stories.”

The book can be found online and at stories such as Target, Barnes and Noble, and Amazon.