Zoonotic diseases are defined as those that jump from animal to human.

We’ve been preoccupied with one such zoonotic disease for the past two years, but health officials aren’t ignoring the others.

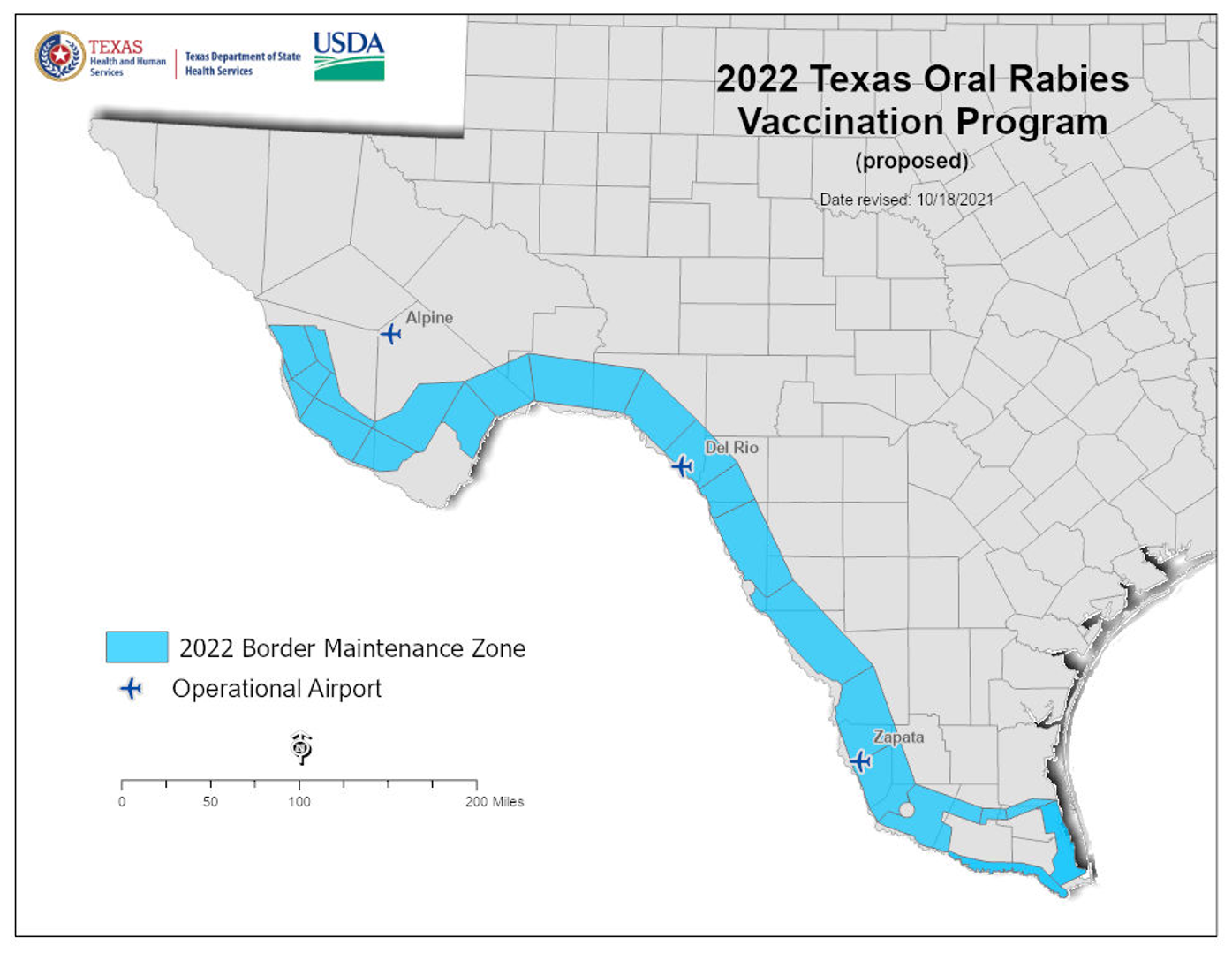

The U.S. Department of Agriculture and Texas Department of State Health Services recently completed their annual aerial drop of rabies vaccine baits over 19 counties and 2,500 square miles along the Rio Grande.

From Presidio to Brownsville, vaccine baits are dropped in an ongoing effort to keep the particularly dangerous canine strain of the disease from spreading among wild species and potentially to humans.

“For the border, what we’re trying to immunize are the coyotes,” said Susan N. Rollo, a veterinarian with DSHS who is part of the anti-rabies effort. “The other species in Texas that we have that carry a different strain are the skunks currently. We used to have the fox strain but we eradicated that strain as well.”

The vaccine baits dropped from the air along the state’s southern border are small, plastic packets dipped in fish oil and coated with fishmeal crumbles, and they seem to be a delicacy for coyotes, gray foxes and raccoons.

Skunks are more particular and don’t take the bait.

“We tried to do the oral rabies vaccine with the skunks, and they just do not consume the baits like the coyotes and the raccoons do, so we weren’t successful in using the baits for the skunks so we do have the skunk strain,” Rollo said. “Unfortunately, because of the skunks, they can bite raccoons, foxes, people, livestock, dogs and cats, so we can get spillover into those species as well.”

Death from bats

The most dangerous vector serving as a reservoir for rabies in the United States are species of bats, and no vaccine-filled oral baits are suitable for these fly-by-night insectivores and frugivores.

In 2021, five people died of rabies in the United States, the highest number in a decade. Three of those fatalities were linked to bat bites or scratches, including a boy who died in Medina County last fall. It was the first confirmed human Texas rabies case since 2009.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said three of the deaths could have been prevented but the victims did not want the shots. One man, an 80-year-old from Illinois, refused the shots needed to prevent the disease because of a fear of vaccines.

The two others, a man from Idaho and the Medina County boy, didn’t think the bats broke their skin and felt the shots weren’t necessary.

If given early enough, the rabies shots can stave off the disease. But if treatment does not commence immediately, rabies is invariably fatal, with only around 30 people worldwide recorded as surviving full-blown rabies throughout medical history.

“It is still a severe disease in humans, especially in other countries where they have a lot of the canine strain rabies,” Rollo said. “We don’t have a way to determine how much canine rabies they have in Mexico. They don’t have a reporting system like we do here, so it’s kind of a grey area.”

Flying the grid

The annual budget for the air-drop of oral rabies vaccine baits in Texas is about $2 million, much of which goes to the aviation contractors.

In this case, they are Dynamic Aviation Group Inc. of Virginia and a Texas Wildlife Services helicopter affiliated with Texas A&M AgriLife. Together they drop more than 1.17 million baits containing rabies vaccine along the Rio Grande.

The staging airports used for air-drop operations were Zapata County Airport, Del Rio International Airport and Alpine-Casparis Municipal Airport.

“They have grids that they fly in, and they have lines that are basically a half a mile apart,” Rollo said. “Each pilot is assigned a certain grid area and they go up from one of those three airports and basically go back and forth, back and forth, until they get the grid completed.”

The numbers indicate the vaccine bait program, instituted in 1995, is working. In the early 1990s before the air-drop vaccine program began, Texas recorded just over 120 cases of the canine strain of rabies in different animal species within the state.

“And since then, we’ve been able to basically push back the canine rabies virus across the border,” Rollo said. “We haven’t found any additional positives in Texas since we started this program.”