By Jolie McCullough, The Texas Tribune

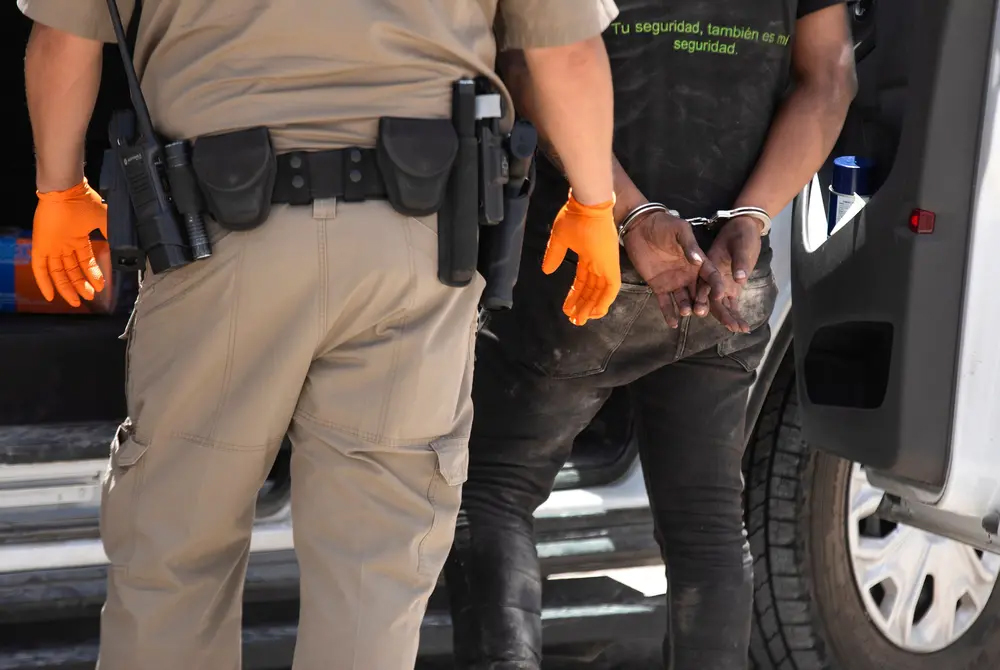

Trespassing charges filed against dozens of migrants arrested under Gov. Greg Abbott’s “catch and jail” border security initiative were dropped last week because court documents filed by the local county attorney failed to point out on what property the men were allegedly trespassing.

The fumble, which ultimately led another prosecutor to sheepishly admit defeat and agree to toss out about 30 cases, is the latest in a string of missteps since Abbott deployed Texas state troopers and National Guardsmen to arrest migrant men suspected of crossing the border illegally on state criminal charges.

The dismissals came during Kinney County’s first court hearings for some of the hundreds of men who have been arrested in the rural border area under Abbott’s initiative, which he began in July in response to a rise in illegal border crossings. Many of the men whose charges were dropped had already spent more than two months in Texas prisons waiting to go before a judge.

They were expected to be released to federal immigration authorities and likely will either be deported, further detained or released into the United States on asylum bonds.

“The fact they have been held for that long on charges that were deemed defective is really disgraceful,” said Amrutha Jindal, a Houston defense attorney whose organization, Restoring Justice, represents nearly 50 migrants arrested in Kinney County.

A sparsely populated region near Del Rio, Kinney County has accounted for the large majority of the more than 1,600 migrants arrested under Abbott’s operation for allegedly trespassing. Most of the county’s arrests occur after Texas Department of Public Safety officers pull people off passing train cars at a remote rail yard or when people are spotted walking across private ranch lands, sometimes caught on game cameras.

Many of the conservative county’s residents have voiced support for the arrests, saying an influx of people crossing the border has led to high-speed police chases, damaged property and general feelings of unease.

“Residents want protection, they want this to end,” Kinney County Sheriff Brad Coe said in August. “[Migrants] are tearing up their livelihood, they’re tearing up their fences, driving off their hunters, and that’s our big industry here.”

But with nearly every step into the new state criminal justice system for migrants, Kinney County officials have stumbled.

When arrests first began in the ranching county, about 150 men sat in prison for weeks without being appointed attorneys, which Texas law requires to happen within days of a person requesting one. In September, a state district judge ordered nearly 250 men, the majority arrested in Kinney County, to be immediately released from state custody on bond because they were being illegally detained, held for more than a month without the state filing charges against them.

In three court hearings for migrants last week, defense attorneys challenged the cases against migrants arrested in Kinney County because the prosecutor’s charging documents didn’t include necessary information — like where the migrant allegedly trespassed, to whom the property belonged and what notice was given to the defendants that entry was forbidden. At least some of the complaints listed vaguely that the defendant “did then and there, with notice that entry was forbidden, enter agricultural land of another.”

Last Tuesday, a retired state district judge assigned to the migrant cases tossed the charging documents and ordered that several jailed men be automatically released from state custody on no-cost bonds until the state filed new paperwork. But defense attorneys continued to push back on continued prosecution, arguing there was no way to hold the men to conditions of a bond for nonexistent charges. By Friday, David McCracken, a Lubbock County prosecutor filling in for the Kinney County attorney, agreed to toss all 20 cases on the day’s docket, conceding that all of the complaints filed against the migrant men were deficient.

Defense attorneys argue the mistakes were not simple clerical errors, instead contributing to migrants’ long stints in jail before they get a hearing before a judge — which in some cases has taken more than three months.

“The paperwork errors are not just mere technicalities. They are serious constitutional violations that are extremely concerning, especially when our clients have been in custody in prison facilities for months based on defective and unconstitutional charging documents,” said Kristin Etter, an attorney with Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, which is being paid by the state to represent hundreds of arrested migrants.

Overall, more than 30 men had their cases dropped last week, while three accepted deals to plead guilty to sentences of the amount of time they had already been in prison. Other men whose cases were set to be heard had bonded out of the state prisons and released to immigration authorities.

Those no longer facing charges were expected to be released to U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials, while those who now had a conviction would likely be transferred to U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement.

Many of Kinney County’s legal mistakes have stemmed from the county attorney’s office, which prosecutes misdemeanor crimes like trespassing. The office has only one lawyer, Brent Smith, who was recently elected to the job without any listed experience in criminal law, according to his LinkedIn profile.

In court, Smith has been noticeably absent, instead enlisting other prosecutors from across the state to act as temporary assistant county attorneys. Kinney County Judge Tully Shahan told The Texas Tribune in September that the high numbers of arrests had overwhelmed the modest judicial system of the county, which has only about 3,000 residents. But attorneys defending the arrested migrants question why Smith isn’t taking the lead or offering explanations as problems continue to surface.

Smith did not respond to repeated requests from the Tribune through email, phone calls and an office visit to talk about the situation. Other prosecutors who have represented his office in court hearings also did not respond to questions.

“It is strange that Mr. Smith has not actually appeared in any of these court proceedings and hasn’t been able to provide any information as to why the charges were filed late or why the charges that were filed were deficient,” Jindal said.

George Lobb, an Austin attorney representing a migrant client, said more concerning than Smith’s absence from court is his activity outside of the courtroom, where he repeats anti-immigration rhetoric in memos and on social media and has spoken against migrants for allegedly causing damage on his own property. Last month, Lobb argued in a procedural court hearing that Smith, who was not present, should be disqualified from representing the state in such cases because of “racist and discriminatory” comments and his public discussion of his own property damage, presenting a conflict of interest.

“His bias, or interests, is brought into question as well as his ability to see that justice is done impartially,” Lobb told the judge, who waved away the argument saying it was not on the day’s agenda.

On Tuesday, more men appeared through Zoom from Texas prisons for arraignments to enter a plea of guilty or not guilty — some of whom had been locked up for nearly 100 days without seeing a judge. Many pleaded not guilty and were ordered to be released on no-cost bonds, likely to ICE, because Smith’s office did not file charges against them within the 30-day deadline under state law, meaning they were illegally jailed.

The state, represented by McCracken and the Kimble County district attorney in lieu of Smith, had filed amended complaints to fix the faulty paperwork errors from last week.

Jindal said last week she expected the prosecutors to quickly fix the errors in their charging documents, but noted that so far the migrants’ criminal cases have largely failed every time they come under scrutiny from defense attorneys. Mentioning other concerns, like only arresting for trespassing men who are predominantly Latino, she said defense attorneys have litigated “just the tip of the iceberg with the issues with these prosecutions.”

“There are still a lot of other issues that will be litigated in terms of violation of rights,” she said.