PHARR — For two years, Gabriel has been working as a chef in restaurants — plural.

The 54-year-old man from Mission originally went to an H-E-B in Alamo to receive his COVID-19 vaccine but said he was turned away because he didn’t have health insurance.

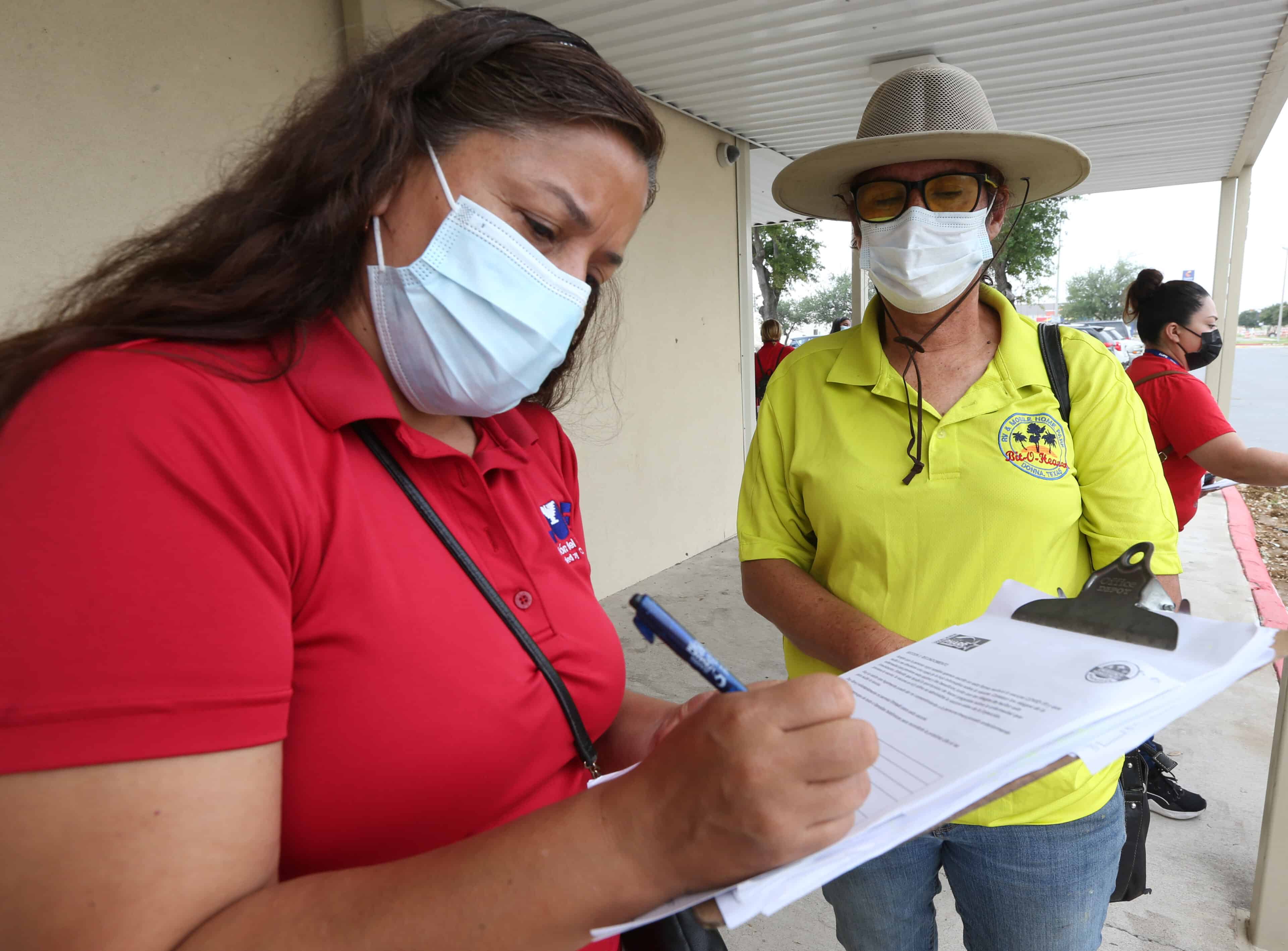

With the help of La Union del Pueblo Entero, or LUPE, Gabriel was one of many local farmworkers who were able to receive their Johnson & Johnson dose Sunday morning at the largest COVID-19 vaccine clinic for farmworkers in Pharr.

Elizabeth Rodriguez, a farmworker justice advocate with LUPE, explained that not only are farmworkers essential workers, but they also lack health care and access to other resources. Furthermore, they face health risks everyday from working in extreme weather, aside from being in enclosed spaces or close proximity.

“They are the highest at risk for COVID, they have the most to lose and their demanding schedule is a conflict, it doesn’t give them the ability to just as easily stand in a long line to reserve a bracelet and go back another day,” Rodriguez said.

The clinic was not open to the public, because all the farmworkers receiving the vaccine were pre-selected by the U.S. Department of Labor with the aid of local organizations and nonprofits. From 10 a.m. until 3 p.m., farmworkers and their families were vaccinated.

For 10 years, Monserrat Ponce’s parents have worked in construction. The 20-year-old and her family all received their vaccine shot Sunday.

She said she heard of people not wanting to take the vaccine out of fear, but pushed back against it, believing it’s important for everyone’s health to take the vaccine.

“I feel good,” Monserrat said after taking her vaccine.

The vaccine clinic for farmworkers was made possible through a coalition that includes the city of Pharr, LUPE, the U.S. Department of Labor, state Sen. Eddie Lucio Jr.’s office, the UT School of Public Health, Texas Rural Legal Aid and the Texas Department of State Health Services.

El Centro de Trabajadores Agricolas Fronterizos, MHP Salud, the National Center for Farmworker Health (NCFH), the Migrants Clinicians Network, Motivational Educational Training (MET) and Migrant Education and Family Support are also part of the coalition.

Previously, according to a news release from the city, about 750 farmworkers were already administered their first dose at Vanguard Academy by Saenz Pharmacy on April 2. According to Pharr spokeswoman Karina Cardoza, approximately 300 individuals attended Sunday’s vaccine clinic.

Mayor Ambrosio Hernandez and city commissioner Dr. Ramiro Caballero were also in attendance, helping administer vaccine doses alongside the Pharr Fire Department.

Due to the city’s crucial role as a port of entry for produce, Hernandez explained they didn’t want the labor force to be at risk, which would further put the supply chain at risk.

“If we get them covered now, it’ll save lives, it’ll help industry, it’ll help keep the economy going, and there’s always a little bit of a shyness that we have for those workers to come forward,” Hernandez said. “They may feel that there will be some immigration questions come up and they’re not. This is not relevant to us, we are here to help every and all human beings within the state of Texas to get vaccinated.”

Hernandez also spoke to various farmworkers and their families, checking on them before they left after receiving their vaccine doses. Many were happy and grateful, with some children teasing their parents because “now they know how it feels,” he said.

As for Gabriel, he said he felt good in Spanish when asked how he felt after receiving his vaccine, adding, “It hurt a little bit, but I’m okay.”

After the H-E-B incident, Gabriel said he got in contact with LUPE, who gave him two options: attend Pharr’s vaccine clinic Sunday or wait and get in contact with H-E-B as to why they refused to give him the vaccine.

Rather than deal with a longer process with H-E-B, Gabriel ultimately decided it would be safer to get the vaccine Sunday.

According to the CDC, the federal government is providing the vaccine free of charge to all people living in the U.S. — regardless of their immigration or health insurance status. As a result, COVID-19 vaccine providers cannot charge individuals for the vaccine, any administration fees, copays or coinsurance; or deny vaccination to anyone who doesn’t have health insurance, is underinsured or out of network.

Gabriel’s incident isn’t the first in the Rio Grande Valley, and he may not be the last.

On Feb. 20, LUPE staff member Abraham Diaz spoke out via social media after UT Health RGV turned away his undocumented father from receiving the COVID-19 vaccine.

After Diaz spoke out, sparking an outcry and a rapid response by the organization, UT Health RGV revealed in a letter addressed to LUPE that 14 individuals were turned away based on their immigration status or residency.

Since then, the university not only contacted those individuals to reschedule their appointments, but they also trained the vaccine staff “to ensure that these errors are not repeated,” the letter stated.

Factors such as immigration status, not being informed of the vaccine guidelines or, in Gabriel’s case, not having health insurance, contribute to individuals’ skepticism to seek out the vaccine for COVID-19, which ultimately puts their life in danger and the public at risk.

“There’s a lot of people that might not have the complete information. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of mixed messages on social media, but we want people to make their own decision,” Rodriguez said, adding that they urge their members to stay properly informed. “We are just passing along the information — the correct, factual information out there — to everybody.”

In addition to being grateful for LUPE’s help in making him aware of the vaccine guidelines and securing a dose for him, Gabriel also hopes the H-E-B in Alamo does not discriminate against people, he said in Spanish.

“They’ve been living here in our community for years,” Rodriguez said of the farmworkers who come from all over the world and are also part of LUPE’s organization. “Some of them might not have legal status, but they are essential workers, they are important to our community.”