A retrospective analysis of migration through the southern border reveals peaks reaching past a million people apprehended by U.S. Border Patrol in recent years, a steady upward trend in unaccompanied children traveling into the United States and a lack of preparation to meet shifting needs.

While the current number of migrants encountered by Border Patrol is comparable with the rates in 2019, a closer examination of the demographics — unaccompanied children, families and migrants excluding people from Mexico — show expected and unexpected trends.

THE CHILDREN

“What is unprecedented is the number of unaccompanied children coming, and we don’t know why. It’s very hard to point to a specific reason for it,” said Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy counsel at the American Immigration Council.

The number of children entering the U.S. without a parent or legal guardian began rising since the agency started reporting the numbers in 2010. In 2014, the totals more than doubled to 68,600. The trend went down only to set a new record in 2019 when over 76,100 children crossed into the U.S. alone.

Numbers fell uncharacteristically in 2020. The start of the pandemic and a mixture of Trump-era policies like MPP, PACR, HARP, which sent migrants away from the U.S., and ultimately the implementation of Title 42, which expelled migrants back to Mexico.

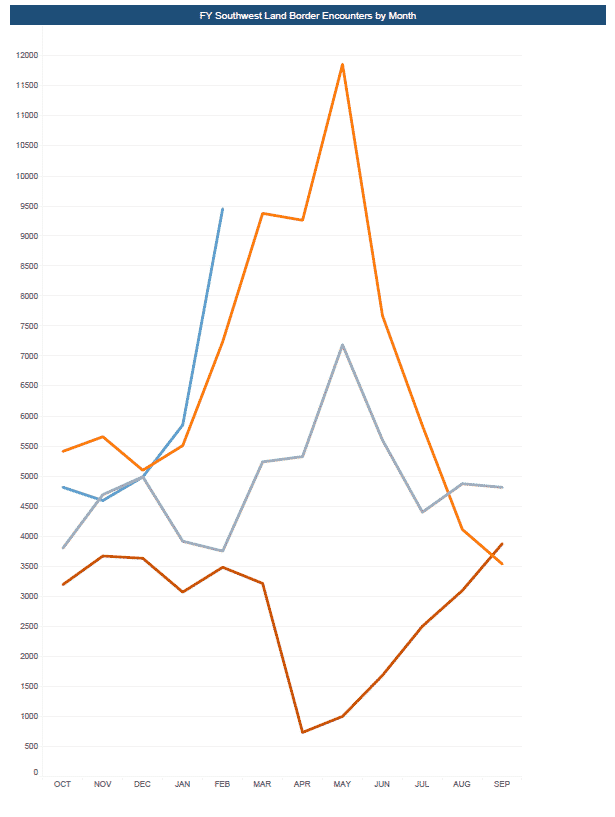

Up until the beginning of this fiscal year, which begins in October, the highest number of unaccompanied children taken into CBP custody was about 5,400 during October 2018.

Four months into fiscal year 2021, a new January record was set when about 5,800 children were taken into CBP custody, about 400 more than those apprehended by CBP in 2019.

THE FAMILIES

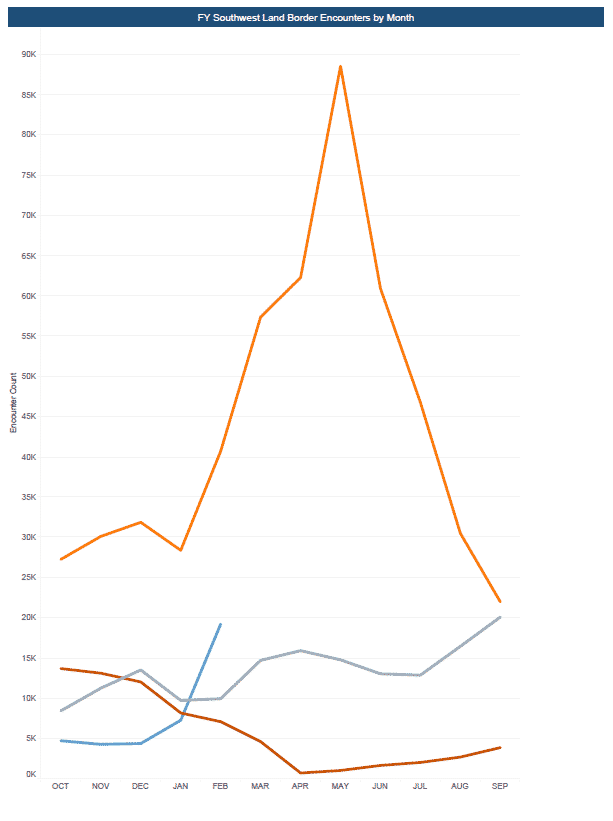

“The number of families coming is not unprecedented; It’s still below 2019,” Reichlin-Melnick said.

More families than ever before showed up to the U.S.-Mexico border during President Trump’s third year in office. Nearly 474,000 families were taken into custody by Border Patrol, a record that increased by nearly 350% from the previous year.

Currently, families are far lower than the records set in 2019. As of February, about 19,000 families were detained by Border Patrol compared to the nearly 36,500 in February 2019.

Certain families entering the country at the moment are still subject to Title 42 expulsions. Some parents with children 6 years of age and younger are released into local communities.

As of March 25, Border Patrol took about 6,000 family members into their custody, according to a source knowledgeable with the situation. Of those, about half were released into local communities and 49% of them were expelled to Mexico.

OVERALL APPREHENSIONS

A look at the data tracking apprehensions by Border Patrol reveal two large peaks in 1986 and 2000, when over a million people were stopped by agents each year.

The last surge of 2019 fell below the million-person-mark with about 852,000 Border Patrol apprehensions. Currently, fiscal year 2021 is poised to overcome the monthly totals from 2019.

While Border Patrol agents have proven to stop more migrants than what they are currently detaining, the pivotal shift in demographics seen in 2019 changed the agency’s ability to detain and process migrants.

MIGRANTS FROM BEYOND MEXICO

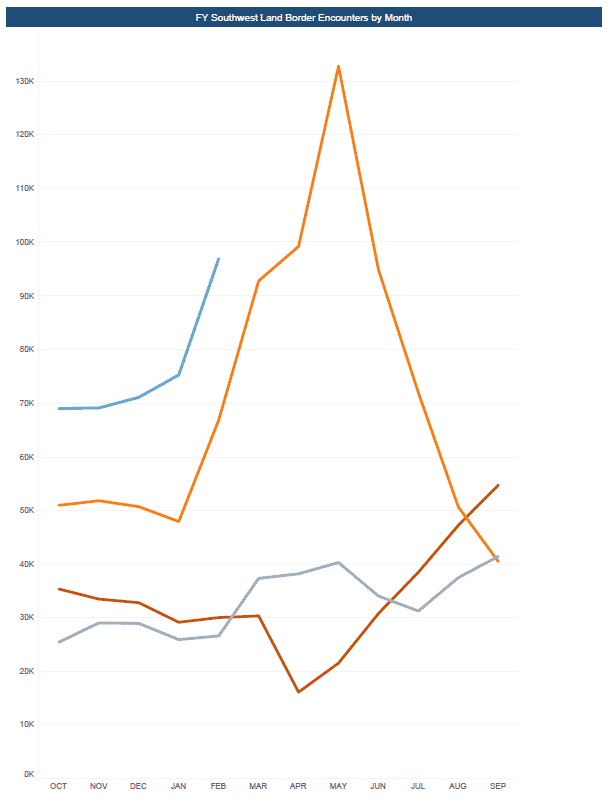

The same year that more families began entering the U.S. seeking asylum was the same year more migrants came to the border from countries other than Mexico.

Border Patrol reported an increase in migrants beyond Mexico since 2014.

At that time, a record of about 257,000 migrants were stopped by Border Patrol. By 2019, about 690,000 migrants were from countries beyond Mexico.

Nationality determines how quickly and in what manner migrants can be processed.

Mexican nationals, especially single adults, can be deported quickly. Those from noncontiguous countries, or countries that do not share a land border with the United States, especially those requesting asylum go through a more comprehensive processing that considers international agreements, or lack thereof.

LACKING INFRASTRUCTURE

“Our facilities were never designed to hold children any longer than you know, a few hours,” a senior Border Patrol official said during a media call Friday.

During the surge of 2019, CBP has publicly acknowledged their detention spaces were designed for the single adults they were processing years ago. Since then, their facilities are overwhelmed with populations for which the architects of the buildings did not account.

The largest building that could hold about 1,000 people in custody for the Border Patrol Rio Grande Valley sector, known as the Ursula central processing center in McAllen, is under renovation to provide — in part — spaces for children.

A temporary tent was constructed in Donna to add holding space during the project, but the growing number of children in custody has led to detention times that exceed the three-day maximum.

MISUSED CBP FUNDS

Politicians are suggesting to surge resources at the border. Already, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security is adding processing space in the Valley and in Eagle Pass.

“It’s notable that the Border Patrol doesn’t have a good history when Congress does give them money,” Reichlin-Melnick said, referring to findings from a 2020 U.S. Government Accountability Office report.

The report studied how U.S. Customs and Border Protection spent congressional funding issued to them to improve medical care after three children died in Border Patrol’s custody from December 2018 through May 2019.

About $112 million were sent to the agency with the intention that funds would be used to purchase consumables and make improvements to medical care.

The U.S. GAO reported CBP did purchase consumable goods like food and hygiene products.

“However, CBP obligated some of these funds for other purposes in violation of appropriations law,” the report stated. “For example, CBP obligated some of these funds for goods and services for its canine program; equipment for facility operations like printers and speakers; transportation items that did not have a primary purpose of medical care like motorcycles and dirt bikes; and facility upgrades and services like sewer system upgrades.

SOLUTIONS ON THE GROUND

Since Border Patrol officials began running out of space in the Valley, they started to release families it could no longer keep in its custody, even through an expedited process.

Space was added at stations across the Rio Grande Valley where tents were seen at the parking lots of the buildings in Weslaco and Rio Grande City.

They’re also working with U.S. Health and Human Services, which has installed an employee at CBP detention buildings to initiate child processing out of federal custody faster. An HHS facility is also under construction at the Donna tent site to expedite child processing and expand space.

HHS recently opened other shelters and intake sites in Carrizo Springs, Midland, Dallas, San Diego and San Antonio to take children out of Border Patrol custody quicker.

DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas activated a Volunteer Task Force to help free Border Patrol agents from performing logistical tasks, an action praised by agents and immigrant advocates.

“The answer is to build up the systems so that Border Patrol officers don’t have to do those duties and can go back to law enforcement,” Reichlin-Melnick said.

He proposes hiring new people to process individuals at the Border Patrol, building new infrastructure to process families and children, and restoring the ability to rapidly adjudicate asylum applications.

Lawmakers are still in search of long-term solutions to address root causes for migration, but that debate will likely continue to be a focus and test of the Biden Administration.