MATAMOROS — Insufficient appointments available for asylum seekers to enter lawfully into the U.S. via a government phone application is provoking families to consider a drastic choice: separating the family.

“This is not family separation, not by the terms that we know it under Trump,” Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, who co-founded a nonprofit organization, the Sidewalk School, and who works with asylum seekers, said Tuesday. “It’s hard to watch.”

CBP ONE APP

Immigrant families who are seeking asylum in the U.S. are still subject to a public health authority known as Title 42, which bars them from seeking asylum in the U.S. But as pandemic restrictions eased, the U.S. started to grant humanitarian exceptions from Title 42 and began processing vulnerable migrants, including children, the elderly and disabled people.

As enforcement of Title 42 continues, though it is expected to end on May 23, U.S. Customs and Border Protection began allowing immigrants the opportunity to request an exception through the CBP One phone application.

The intended effect was to reduce the number of illegal crossings between the ports of entry and redirect those seeking asylum to the application.

Since its roll out, however, the application has been plagued with problems like excluding the language spoken by Haitians, one of the largest groups who have been waiting for over a year across the Valley’s border to request asylum.

A spokesperson with CBP who spoke on background said the administration made improvements to the app, including adding the new language. But now, a new problem surfaced last week that’s leading families to face a choice no parent wants to make.

LEFT BEHIND

My sixteen-year-old told me, ‘Go, mom. You should go.’ But how can I go and leave them behind?

After a virtual meeting with Texas Civil Rights Project attorneys, a 40-year-old Venezuelan mother, who preferred to go by Maria for safety reasons, held her head between her hands as her face turned red and wet, overwhelmed with tears.

“I feel like I’m going to have a stroke,” Maria said.

The meeting helped provide information to parents considering sending their children to request asylum at the bridge, often with an adult family friend. Unaccompanied children are processed faster than families or adults, because of their vulnerability.

But sending children on their own, the attorney warned, can mean the child will be in a federal shelter for weeks or months before a guardian is vetted.

Maria arrived in Matamoros a few months ago with her husband, 16-year-old son, 19-year-old daughter, and 23-year-old son. Their mother stood up to ask the attorney a question.

She and her husband had appointments that were days apart but their children did not have an appointment.

But there was no solution for her problem.

“My sixteen-year-old told me, ‘Go, mom. You should go.’ But how can I go and leave them behind?” Maria recalled in a tearful interview. “I’m here, because of them.”

Both her daughter and son are deaf, cannot speak, and communicate through sign language. Her daughter, who is married and traveling with her husband, managed to get an appointment.

Her eldest, however, is severely disabled after he was diagnosed with meningitis at two years of age. He was hardly able to move as a child, but after surgeries and Maria’s lifelong dedication to his health, her son gained some mobility, though he still uses a wheelchair for long walks.

Maria’s son requires constant vigilance and cannot be independent. His hands tend to fold into themselves and he has little control over his jaw.

Both parents do odd jobs or sell candy to help buy food and other necessities, though they’re staying at a shelter.

Maria showed screenshots of the multiple configurations they tried while seeking an appointment through the CBP One app, but she only got to the prompt in the application showing her any slots when it was just her.

Maria has an appointment on Friday, and her husband has his in two weeks. They’re considering their options.

Maria can keep her appointment on Friday and enter the U.S. while the two sons are sent to the bridge as unaccompanied children. However, she hadn’t considered her eldest son’s age beyond the age of a minor.

I have my appointment but what good is it if the kids, who are the most important, are not on it?

Unaccompanied children are given priority as asylum seekers due to their vulnerability.

Then, Maria’s husband can cross after their sons are in the U.S.

But there are no guarantees their plan will work and the family can become severed by the Rio Grande — Maria’s son would go without his mother’s care.

Maria said she’s suffered mental, emotional and physical harm after trying to enter the U.S. “the right way” as opposed to the many who have tried asking for asylum after entering illegally between ports of entry.

Maria is one of many families considering options that will tear their families apart.

A young Haitian single dad traveling with his two-year-old daughter has an appointment in a few days, but his girl is not on the list. One option is to leave her with someone, though he isn’t traveling with friends or family.

“With what heart do I give her up so I can go in [to the U.S.] and leave her alone not knowing how much longer I will be able to hold her in my arms?” the Haitian father said.

He preferred not to be identified for safety reasons.

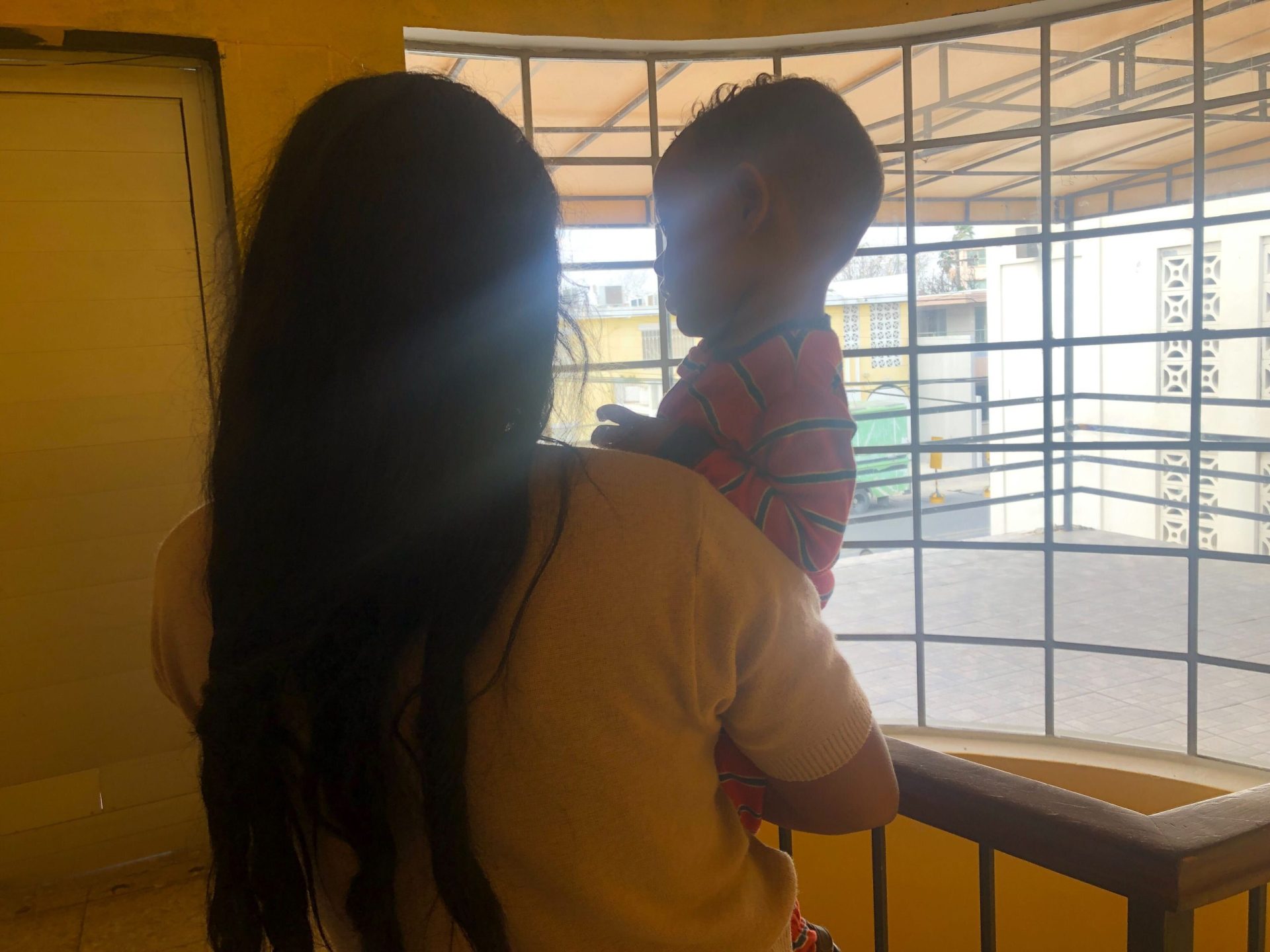

“What do I do, God?” another Venezuelan mother said while cradling her baby a few days short of two months old. She, her husband, and two children are facing a similar choice.

“I have my appointment but what good is it if the kids, who are the most important, are not on it?” her husband said. “The kids are getting set aside as if they didn’t care for them.”

SUDDEN ENFORCEMENT

Although a CBP spokesperson explained they did not change policy, something did change.

The couple, the Haitian father, and the Venezuelan mother with the disabled son who spoke to border officers at the ports of entry in Reynosa and Matamoros were told they could bring their families, with official documentation, if at least one of the parents had an appointment.

Next thing I know, there it is, at the bridge, you’re seeing it — people are being forced to make the decisions, families are fighting, there’s crying, they’re screaming.

Many crossed that way, according to Rangel-Samponaro, who visits immigrants in Reynosa and Matamoros on a nearly daily basis. But, it was not meant to be used that way.

“When it first came out, it was more lenient. They were not as strict on everyone having to be on the appointment in order to cross,” Rangel-Samponaro said.

As the app saw improvements, Rangel-Samponaro said she noticed a tightening of reins. “What happened last week was that they decided to enforce it.”

For some families who witnessed families crossing intact one day and then learning of the new enforcement the next, the change was felt immediately.

“So, people had to make decisions on that bridge,” Rangel-Samponaro said.

Over on the Hidalgo bridge connecting with Reynosa, Priscilla Orta, an attorney working with Lawyers for Good Government, was in line last Wednesday waiting to cross back into the U.S.

“Next thing I know, there it is, at the bridge, you’re seeing it — people are being forced to make the decisions, families are fighting, there’s crying, they’re screaming,” Orta said.

Families she spoke with also reported feeling jilted by the sudden enforcement that meant they’d have to make a quick decision.

Orta returned to frantic families in Reynosa the next day with questions that CBP is attempting to address.

“I think what’s happening now is that they are trying to correct the issue,” Orta said. “But it’s a pretty big issue, because there are no slots,” she said, referring to the appointment slots available. “They’re gone sometimes by 8:03 a.m. We have sometimes seen that the spots are gone by 8:01 a.m. And everyone knows it.”

The odds of obtaining an appointment appear to increase when the number of slots sought decreases, Orta explained.

“I’ve never seen since the first week,” Orta said, referring to families obtaining appointments, adding, ”I’ve never seen or heard of a family unit being able to get spots. I’m sure there are people who have been, I’m sure there are. But the overwhelming majority of people … they say, ‘Look, we can’t get appointments, it says everything’s ready. Everything’s good to go.

“But the minute I click enter, it says there are not there are no spots available.’”

The practice of sending kids without their parents is not uncommon, Orta said.

On Monday, Orta said about a dozen people crossed, but all of them had already sent their kids as unaccompanied minors without them by that point. They hoped they would be reunited, but “they didn’t understand that their children wouldn’t be waiting for them 24 hours,” Orta said.

A LIMIT

A CBP spokesperson who spoke to The Monitor to provide background information said CBP is limited in the number of appointments it can offer due to a court order from Louisiana.

The federal government was ordered to keep track and report the number of people allowed into the U.S. through the exception program. According to filings, about 21,800 people used the CBP One app to enter the U.S. It was a decrease from the nearly 23,025 people who crossed through the similar process in December 2022.

The states who filed the Louisiana lawsuit against the federal government to keep Title 42 in place are keeping careful vigilance over the numbers and even recently filed a motion stating they believed the federal government was increasing the number of appointments without proper notification to the court.

The app also does not allow for any kind of priority given to groups, either single adults, couples or families. Those seeking one slot will have an easier time to find one than someone looking for a group.

For now, there appears to be no solution for families stuck between the math, policy and practice other than to keep trying.

“My answer is the same,” Rangel-Samponaro said when she spoke with parents wavering between options. “Cancel your appointment and try again. Start all over again.”