BY ALLAN HUGH COLE JR.

Sixteen words from my doctor changed my life: “What worries me is that I think you are in the early stages of Parkinson’s disease.” I was 48 years old.

Recently, I stopped by my local pharmacy to pick up my Parkinson’s medication. As I waited in line, a woman told the pharmacy tech, “I absolutely have to have those pills,” pointing to a small white bag in the tech’s hand. “I can wait on the other two till next time. I’ll get them when I get my check.” She seemed to have made these kinds of choices before.

I imagined that trying to decide which medicine to prioritize felt like having to choose between food and water, or between clothing and shelter.

As the tech got the revised order ready, the woman walked slowly to an adjacent aisle. A different pharmacy tech called me to the counter. I told him my name, and he turned around and began looking for my prescription in alphabetized bins. If I had no health insurance, my meds would cost me $700 a month. In some places, that’s an entire month’s worth of housing. I prepared my $10 co-pay, all the while thinking about the woman waiting for what she could afford and what she had to do without.

One month later, I stood in the same line. A man about my age was at the counter. His tanned skin, torn jeans and dirty work boots suggested he worked construction. Hearing that his medication would cost $560, he dropped his head. “I can’t pay that,” he said, and walked out.

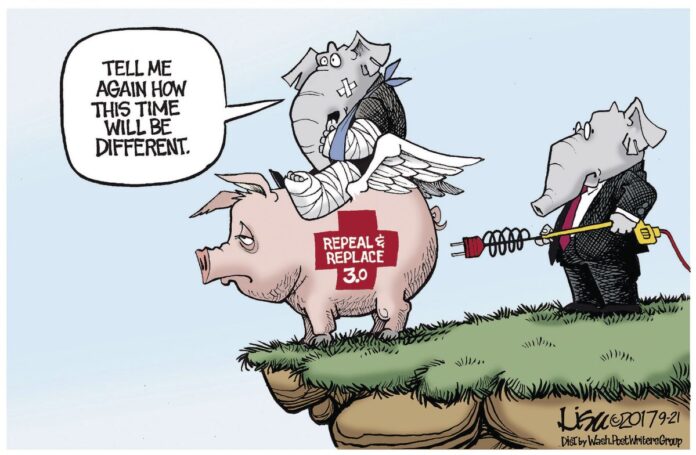

If the Graham-Cassidy plan becomes law, these scenarios will likely play out more often.

The Senate’s latest version of a “repeal and replace” plan for the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) would give individual states responsibility for providing coverage to Americans with low to moderate incomes. Though many governors oppose it, particularly in states that expanded Medicaid under Obamacare, block grants would be awarded and states would be left on their own to decide on coverage levels and strategies, with little federal oversight. While some states are safer bets than others to provide adequate and affordable coverage, any plan should include mandates for covering the cost of prescriptions. These drugs keep chronic illnesses in check and delay or help avoid catastrophic expenses associated with a medical condition spiraling out of control. The idea that it is frugal to trim costs on prescriptions is simply short-sighted and untrue.

But as Graham-Cassidy takes shape, many other questions abound, like whether the working poor, those with pre-existing conditions, or those whose employers opt not to provide health benefits will, in effect, have no affordable options for coverage, including coverage for prescription medications.

A recent analysis by the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation found one in four people have pre-existing conditions that would have made it difficult for them to get health insurance prior to the Affordable Care Act becoming law. If its protections for pre-existing protections were repealed, then 52 million people under the age of 65 would have difficulty getting private coverage. Any new plan must include viable coverage for all, regardless of existing conditions.

I am fortunate. My job provides my family with a measure of security that many in our country lack, whether they have Parkinson’s disease or another illness. I have health insurance and a prescription plan. I don’t have the same worries that the two souls at Walgreen’s endure.

But we all have a moral responsibility to advocate for a healthcare plan that covers our nation’s most vulnerable people. We have a responsibility, through taxes, to help pay for it. All members of a just society share this responsibility.

While the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office will not have time to properly evaluate the Graham-Cassidy plan — before it’s expected to be rushed to a vote this week — many economists have noted a concern that, if it passes, millions of Americans risk having inadequate healthcare coverage.

We must insist that our elected officials vote against this plan. Sixteen words, or fewer, could change anyone’s life.