|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

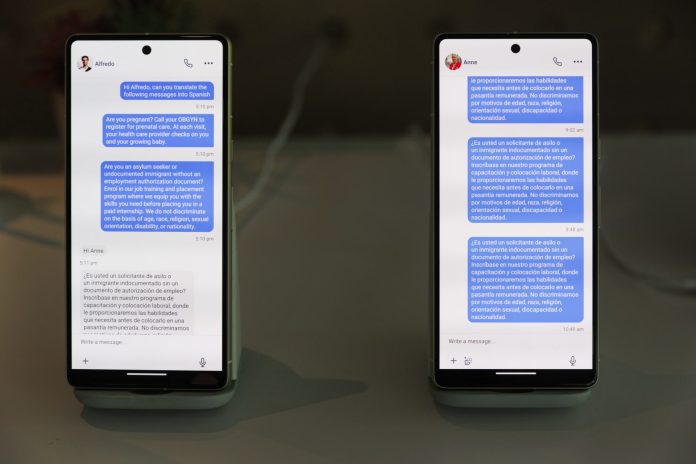

A mobile phone company is running ads on television and online streaming channels promoting an app that can provide immediate language translation using voice-recognition software. Such technology could help address the growing need and complexity of dealing with people who don’t speak English in our legal and immigration courts as well as other government functions.

The Cardozo School of Law in New York recently issued a report regarding a survey of immigration and legal services that found our Immigration and Customs Enforcement Department fails to provide adequate translation services to many of the people they encounter and detain. That failure has left many immigrants unable to understand the actions and decisions that affect them, and in many cases unable to receive adequate medical care when they needed it.

Those services are required by federal law and the policies that govern the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE, Customs and Immigration Services, Border Patrol and other agencies that deal with foreign-language speakers.

According to the report, most of the people the researchers surveyed reported that they never received language assistance at all during their detention and proceedings. They often sought help from other detainees when they had to fill out forms that were only provided in English.

Many of them reported that they were unable to request medical attention when the needed, and their needs often weren’t addressed until their conditions worsened and became obvious to their caretakers. Even then, they often had to deal with doctors and other medical staff who didn’t speak their language and their problems at times were untreated or misdiagnosed.

Courts of law have similar issues. The Department of Justice has issued a directive to state courts noting that all agencies that receive federal funds must abide by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and failure to provide adequate translation services violates the act’s prohibition of discrimination according to national origin.

The need for translators is becoming more complicated as the flow of immigrants grows more diverse. In the Rio Grande Valley and elsewhere, migrants increasingly are from Haiti, Asia and other countries. ICE last year detained people from 170 different countries; the United Nations recognizes 195 countries worldwide.

A policy change seems in order. Officials should recognize the potential of using AI-assisted translation apps, test their accuracy and effectiveness and utilize them if they are deemed adequate.

Certainly, a computer could be a cost-effective measure to help ICE and the courts address their translation needs. Of course, however, the priority must be to best serve the people who come before them. However, a well-designed and tested app could help agencies address those needs when a live translator is unavailable.

As technology becomes more advanced and sophisticated, government agencies should be willing to test their potential and utilize them when it can improve their functions and improve the outcomes for them and the people they were created to serve.