|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

One rainy day last week, a man entered an Edinburg grocery store carrying an umbrella. Before long local internet accounts were roiling with news that someone had taken a rifle into the store and threatened the public.

It wasn’t true.

This week thousands of people across the country have kept their children out of school because of reported threats following last week’s shooting at a Georgia high school. So many children have been absent that some Rio Grande Valley school districts issued public notices that the reports weren’t true.

Access to the internet has quickly become nearly universal. If you have a mobile phone — and who doesn’t these days? — you have endless ways to get information.

This is both good and bad, especially for voters and others interested in the operations, and operators, of government. Gathering information about issues, officials’ actions and candidates’ positions takes a simple query to an internet browser through a cellphone or other device with internet access.

Unfortunately, some people use, and abuse, this freedom to spread lies, exaggerations and other errant information that can lead to bad perceptions, bad conclusions and bad votes.

Many political figures warn of false information. Unfortunately, many of those same people are among the worse culprits, and apparently seek to destroy trust in legitimate information sources in order to spread their own lies more easily.

Misinformed voters could be more at risk of electing people who might be corrupt or don’t truly represent the voters’ wishes.

It’s important, therefore, to be skeptical of information that’s available online; the fact that it’s published doesn’t mean it’s true — even if it comes from what might be considered official sources. In just the past week, an adviser to Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign was charged with working for a Russian media network and thus violating federal laws regarding foreign intervention in our election process, and a Missouri judge ruled that an official in that state intentionally used “unfair, insufficient, inaccurate and misleading” information on an official summary of an abortion-related ballot measure in order to sway the vote.

The problem has created a fast-growing industry of fact-checkers that evaluate news and political statements.

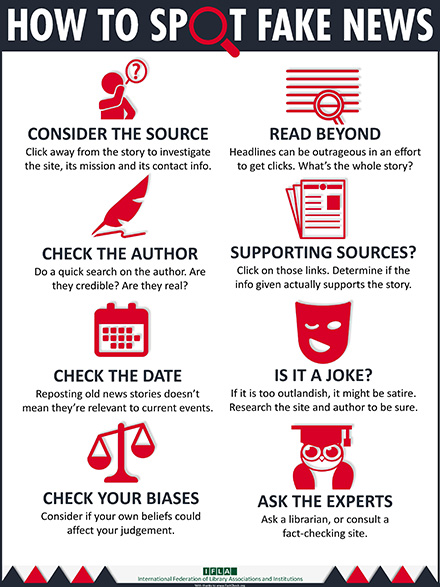

Internet users also should do what they can to verify information they encounter online, online and elsewhere. In fact, it should become a habit.

But how do we know what information can be trusted and what shouldn’t?

Analysts recommend make your own verifications. Know the sources and their reputation for accuracy. Determine if their information benefits them or harms their opponents. See if others provide the same information independently of each other. Legitimate outlets provide the sources of their information, enabling people to go to those sources themselves for verification.

News media have used these safeguards for years. With more information available directly from other providers, it’s good for everyone to exercise the same skepticism, and try to ensure that the information they are getting is believable.