One of the most bizarre things to come recently from Texas’ two senators, John Cornyn and Ted Cruz, is their promoting a resolution honoring the 200th anniversary of the Texas Rangers.

Given their well-documented history of brutal violence and racism, it is a sham to sing their praises, as the senators did, calling them “the oldest state law enforcement agency, upholding public safety in the Lone Star State.”

The Rangers’ history is a far, and bloody, cry for enforcing the law and upholding public safety. Their brutal and violent history is well documented.

As a “law enforcement agency,” the Rangers were unofficially founded in 1823 as a “punitive expedition against a band of Indians,” according to the Texas State Historical Association. They continued to drive indigenous people from their homelands during the Cherokee War in 1839 and the Plum Creek battle against the Comanches in 1840.

In the mid-1800s, the Rangers launched the infamous Callahan Expedition to capture hundreds of runaway enslaved Black people seeking freedom in Mexico, again according to the Historical Association.

In 1918, the Rangers slaughtered Tejanos during the notorious Porvenir massacre near El Paso. A group of Rangers, U.S. Army soldiers and ranchers arrived at the Porvenir village, seeking revenge for cattle raids by Tejanos along the border. There was absolutely no evidence implicating the villagers in the cattle raids, but the Rangers nevertheless took 15 men and boys from their families and summarily executed them, joining together racism and white violence.

So many Tejanos and Mexicanos — hundreds, perhaps thousands — were slaughtered between 1910-1920; that the era is called “la Matanza.” There are abhorrent photos of the Rangers posing with their dead or nearly dead victims.

In the mid-1950s, Rangers helped Gov. Allan Shivers resist a federal court order to desegregate Mansfield High School by keeping Black students from attending class. A photo shows a Ranger amicably chatting with white students while a Black effigy hangs over the school’s front entrance.

In many ways, the Rangers did help bring law and order to the Texas frontier, although some of the disorder resulted from dispossessing people of their land, whether Native American people or Tejanos. But the Rangers’ early history is very dark. It would not be an overstatement to depict them, as have some authors, as a marauding band of quasi-legal gunmen who had a hand in massacres, lynchings and other atrocities against Mexicans and Mexican Americans. As one south Texas resident put it, the only difference between the KKK and the Rangers is that “we could see their faces.”

There are still Hispanic elders alive who can recount the Rangers’ violence against their families and are telling their stories in oral histories. Some people were simply shot in the back by Rangers, apparently for the sport of it; it’s the oppressor’s way of making their point.

The Rangers finally lost their independence when the legislature, after a 50-year struggle by the Hispanic community, brought them under the control of the Department of Public Safety.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was the brutal way in which the Rangers, under the command of the notorious Captain A.Y. Allee, suppressed the United Farm Workers’ strike in 1966-1967 at La Casita Farms in Starr County.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Rangers in 1974 in a lengthy opinion detailing the Rangers’ chilling violence and law-breaking against the workers, organizers and supporting clergy. The legislature had no choice but to rein them in, converting them into an investigative arm of DPS, and getting them off the street.

Cavalierly honoring the Texas Rangers is a slap in the face to Texas’ Hispanic, Black and indigenous communities. It is also a slap at history.

Texas Republican leaders these days seem hell-bent on rewriting history to powder over its ugly warts, rather than using it as an opportunity for change. Trying to rewrite history is offensive; Cornyn and Cruz should stop trying.

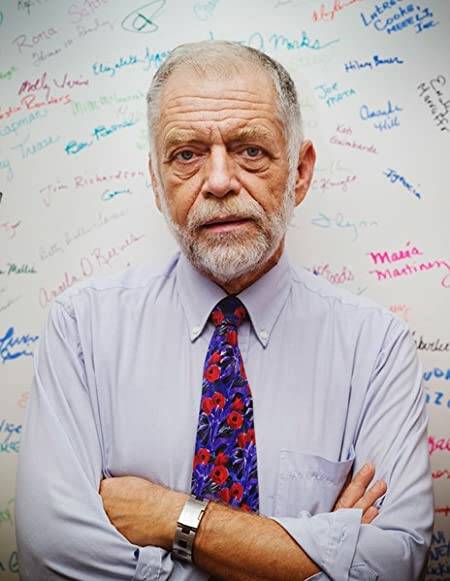

James C. Harrington is the retired founder of the Texas Civil Rights Project.