|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Between the unseasonably warm waters already occurring in the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, and the high likelihood of a La Niña developing later this year, weather scientists are predicting that the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season may be one of the busiest on record.

And it may have the potential to be one of the most destructive.

“NOAA is predicting an above-average 2024 Atlantic hurricane season. Specifically, there’s an 85% chance of an above-normal season, a 10% chance of a near-normal season, and a 5% chance of a below-normal season,” Dr. Richard W. Spinrad said during a livestream broadcast on Thursday morning.

Spinrad serves as the chief scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which typically unveils its Atlantic hurricane season forecast just before Memorial Day.

As part of Thursday’s forecast announcement, Spinrad said NOAA expects the upcoming hurricane season — which begins on June 1 — to produce between 17-25 named storms, with 8-13 of those expected to become hurricane strength.

Of those that turn into hurricanes, 4-7 are expected to become “major hurricanes” — those that grow to Category 3 or higher storms with winds in excess of 111 mph.

The weather chief paused to note that that prediction represents the highest number of storms that NOAA has predicted prior to the start of hurricane season.

“The forecast for named storms, hurricanes and major hurricanes is the highest NOAA has ever issued for the May outlook,” Spinrad said.

Further, other hemisphere-spanning climate patterns are likely to exacerbate the severity of the storms right at the peak of the season.

“The official CPC forecast issued just this month indicates a 77% chance of La Niña forming during the August-October timeframe,” Spinrad said, referring to NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

La Niña is a climate phenomenon wherein surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean tend to cool. That leads to “weaker easterly trade winds,” Spinrad said.

La Niñas also produce less windshear in the upper atmosphere. Without that shear, tropical cyclones can climb high into the sky and grow in strength unabated.

Last summer, an El Niño climate pattern kept hurricane activity to a minimum, its windshear lopping the tops off of tropical weather systems as they formed, not unlike someone scraping the frosting off a cupcake.

Nonetheless, the 2023 season caused billions in damage.

“Last season, even with most Atlantic tropical activity remaining offshore from the United States, tropical cyclones caused approximately $4 billion in damages for the contiguous U.S.,” Spinrad said.

That figure includes damages caused by storms that originated in the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. Hurricane Hilary, a rare Pacific cyclone that struck California, caused nearly $1 billion in additional damages.

Aside from the coming La Niña, the waters of both the Atlantic and Gulf are experiencing abnormally early levels of warming. Currently, water temps are more akin to what the two bodies of water experience during La Canicula — the height of summer in August.

“The sea surface temperatures in the main development region are 1-2 degrees centigrade higher … closer to what we’d see in August,” Matt Rosencrans, a CPC meteorologist said.

He called the current ocean conditions “dramatically warmer.”

Warmer ocean waters act as jet fuel for a tropical cyclone.

“We know warm sea surface temperatures are an important factor in rapid intensification of tropical cyclones to major hurricane status, and that major hurricanes contribute significantly to the measurements of ACE, the ‘accumulated cyclone energy,’” Spinrad said.

Aside from the forecast calling for the highest number of storms in NOAA’s history, the agency is also predicting that the 2024 Atlantic season will have the “second-highest ACE for our May outlook,” Spinrad said.

“In past years, when we’ve seen high ACE numbers, those have historically been the years with the most destructive hurricanes,” he said.

Taken all together, that amalgamation of variables occurring all at once can spell disaster when it comes to giving people ample warning of a coming storm, especially the most destructive of those storms.

“The big ones are fast,” said Ken Graham, director of the National Weather Service.

“In the last hundred years, every single one of these big storms, Cat 5s, were a tropical storm or less three days prior. Several didn’t even exist three days prior (to making landfall),” Graham said.

On those Category 5 (hurricanes), the average lead time’s 50 hours,” he added a moment later.

Graham said storms care not for the “timelines” set by the people they impact, referring to the emergency management plans that local officials often have in place to help guide their storm response.

In the Rio Grande Valley, for instance, many emergency managers have a checklist of things to begin doing at 100 hours ahead of landfall, 72 hours, 48 hours, etc. — things like warning the public, making evacuation decisions, and staging emergency responders and supplies in strategic locations.

But when a major hurricane can form and strike in just two days, those timelines don’t matter.

“Preparedness. We’ve got to be ready for these storms,” Graham said.

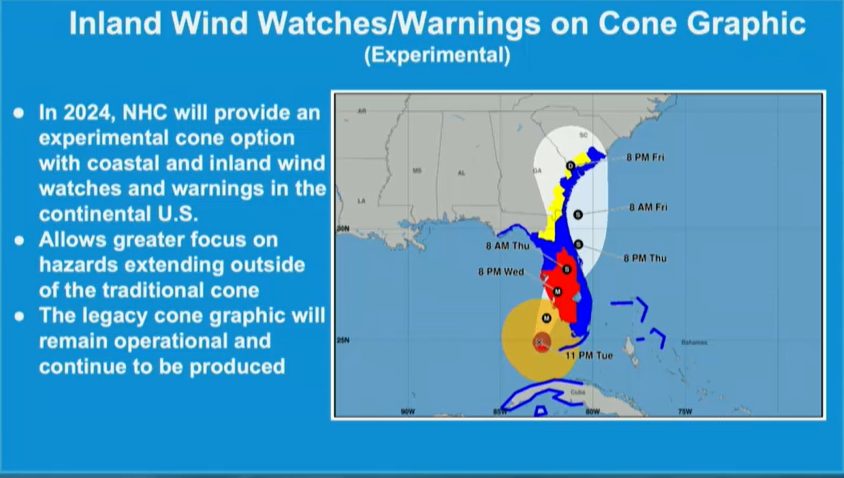

To that end, the National Weather Service will be unveiling a new tool this season that they hope will give both coastal and inland residents a better idea of how a tropical cyclone may affect them.

The NWS has revamped the “cone of uncertainty” — the illustrations that any coastal resident who watches a TV weather forecast will be familiar with.

Typically, the cone provides a visual representation of where forecasters think a tropical cyclone will go about “two-thirds of the time,” Graham said.

This year’s new cone of uncertainty will now also illustrate how that storm may impact the surrounding region.

“We’re also going to put our watches and warnings, we’re going to put the impacts on the map,” Graham said.

Finally, Erik A. Hooks, deputy administrator of FEMA, urged people to plan now because once a storm forms, it’s usually too late, he said.

“Take time to make sure that you have a clear understanding of your unique risk now,” Hooks said.

He urged people to think about their medical needs — including how power outages could impact medicines that need refrigeration, medical devices that need electricity to operate, or how mobility issues could affect evacuation plans.

“Now is the time to ask yourself these questions, understand your risk and put a plan in place so that you’re prepared when disaster strikes,” Hooks said.

“That’s what resilience is all about.”