A foundation of porous prehistoric limestone is putting the structural integrity of the Amistad International Dam at risk of failure with the potential to impact hundreds of thousands of people living downstream.

The concerns are so serious that experts with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have rated the structure as “Class II,” or a matter of “urgent” concern, on their five-point rating scale of dam safety.

Class V dams are considered safe, while Class I are considered an “urgent and compelling” risk of imminent failure, according to a dam safety policy manual the Corps published in 2011.

Amistad, with its Class II designation, is considered high risk, with “the likelihood of failure… too high to assure public safety,” the policy manual states.

“In 2007, the IBWC technical advisers concluded that the entire foundation of the dam is potentially unsafe and required further evaluation and study,” explained Karla Benitez, a civil engineer with the International Boundary and Water Commission during a public webinar on Wednesday.

Should the dam fail, scores of lives could be put in danger.

“During the high pool of the dam, approximately 300,000 to 400,000 (people) could be impacted in case of a dam failure,” Benitez said.

“High pool” refers to the maximum capacity of the reservoir behind the dam before water would overflow the top. Amistad reservoir has the 12th largest storage capacity in the country.

A dam failure would also cost billions in damage from lost international trade and commerce, loss of irrigation water to downstream farmland, as well as the freshwater supply downstream communities depend on.

The problems at Amistad aren’t new. In fact, IBWC officials first discovered issues in 1994 — some 25 years after the dam’s construction was completed in 1969.

Severe drought had uncovered a series of sinkholes on the upstream side of the dam, which lies just north of Del Rio.

“The first sinkhole began to appear in the reservoir near the earthen embankment on the Mexican side,” Benitez said.

That discovery led to daily inspections of the sinkhole, along with a more formal analysis of the issue by a binational group of analysts from both the IBWC and its Mexican counterpart, La Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas, or CILA.

Ultimately, the sinkhole was filled in with grout and stones known as “riprap.”

But the sinkhole wasn’t a one-off. Instead, it was a symptom of a much larger issue.

The problem lies with the prehistoric bedrock upon which the international dam was built, known as “karstic Georgetown limestone,” Benitez explained.

Underneath the thin soil that blankets Val Verde County and Cuidad Acuña in Coahuila, Mexico lies a thick layer of porous limestone that dates back 100 million years to the last age of the dinosaurs during the Cretaceous Period.

One study of the region’s geology by the U.S. Department of the Interior estimated that the limestone is between 450-600 feet thick.

Limestone can be found throughout Texas, and makes for some of the clearest, purest aquifers. But as rocks go, limestone is also very soft.

The very same porous characteristic that makes it a great filter for clean water also makes it incredibly susceptible to erosion. And that’s exactly what has happened at Amistad.

The reservoir’s 5.6-million-acre feet capacity — or more than 1.8 trillion gallons of water — puts a lot of pressure on the substrate underneath.

That pressure causes the water to seek equilibrium. It begins to seep into the pores of the soft bedrock, looking for a path toward less pressure.

Eventually, the seepage wends its way underneath the bottom of the dam, where the water bubbles back to the surface via springs on the other side.

“Cavities are present at all kinds of points along the cross section of the dam,” Benitez said.

“And there’s interconnections between upstream sinkholes and downstream springs,” she continued, adding that officials proved the two phenomena were linked by dyeing the water on the upstream side and following it to the other side.

Put simply, “the sinkholes endanger the dam,” Benitez said.

The engineer explained that both U.S. and Mexican officials have been studying the problem since that first sinkhole was discovered in 1995.

Together, they created a “safety mitigation plan” to explore potential solutions and found three possible courses of action.

Two of the proposals would do little more than kick the can down the road.

They involve “overbuilding” either the upstream or downstream side of the dam to temporarily shore it up — essentially, piling material onto one side of the dam or the other.

But doing so would fail to address the root issue of water seeping underneath the dam entirely.

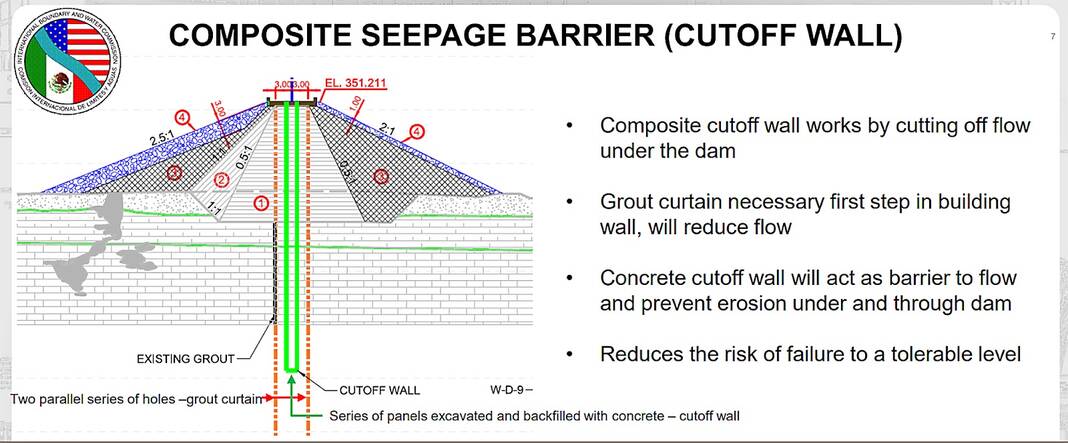

Instead, the IBWC has settled on a more involved solution called a “composite seepage barrier.”

The barrier would consist of two main components — a “composite cutoff wall” and a “grout curtain.”

“The composite seepage barrier is designed to intersect and cut off the flow of water to the karstic bedrock foundation below and through the embankment core,” Benitez explained.

It will have to be constructed in phases, with the grout curtain built first.

Essentially, cores will be drilled into the earth in a line on either side of the dam, similar to how holes are dug for fence posts.

But these holes will extend deeper than the base of the dam — and far deeper than the Georgetown limestone — into the harder rock underneath.

The holes will then be filled with pressurized cement grout, Benitez explained.

The two-paneled grout curtain alone won’t completely abate the water seepage underneath the dam, but it will slow things down enough for engineers to tackle the next phase of the project — the cutoff wall.

The cutoff wall will be positioned between the two grout curtain panels, nestled closer to the walls of the dam. It will be made of impervious concrete that will serve to prevent further erosion of the limestone bedrock.

Benitez did not say how much the dam remediation project will cost, but did say that those costs will be shared by both the U.S. and Mexico as outlined by international treaty.

Though nearly three-fourths of the 6-mile-long dam lies in Mexico, the United States will take on a greater share of the cost burden to repair it — 56.2% to Mexico’s 43.8%.

The phased work will take several years to complete — approximately 11 months to design the two barrier systems, then another 18 months to construct the grout curtain before construction of the cutoff wall can begin.

Officials hope to begin on Phase 1 by June 2024.

However, they still don’t know how deep the two barriers will have to go. That, Benitez said, has yet to be determined.