|

Only have a minute? Listen instead

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

EDINBURG — Weighing in at a grand total of 2 pounds 7 ounces, little 12-day old Rebekah Espinosa finds herself at the forefront of a study at DHR Health Women’s Hospital that may ultimately help micro premature babies like her make it home from the hospital sooner and be healthier when they get there.

Born at 28 weeks old, Rebekah resides in the neonatal intensive care unit, and she lay there Monday in one of the dozens of incubators lined up in rows.

The babies are nestled in blankets under the plastic shields, connected to hoses and tubes and flashing monitors.

Rebekah’s fingers and toes are smaller than Tic-Tacs. A lighted node bandaged to her foot shines straight through, transparently. She’s smaller than most babies, but bigger than some of her roommates in the NICU.

Monitors constantly beep and buzz in the unit. Staff quietly glide among the incubators, treating their patients. A woman sits quietly by an incubator just down from Rebekah, staring at the baby inside. Another couple sits quietly by another baby in another row, staring just as intently.

Rebekah’s mother, who is 21, hasn’t been able to hold her daughter. The appeal of some sort of treatment to get babies strong enough to leave the NICU earlier is abundantly evident.

In technical terms, the treatment Rebekah is undergoing is oropharyngeal therapy with her mother’s breast milk or colostrum, allowing the immunoprotective components of the milk to be absorbed by the lymphoid tissues of the oropharynx.

Put much simpler, a speech language pathologist gently syringes two drops of milk into the inside of Rebekah’s mouth every six hours, the goal being to make her stronger faster and to get her out of the NICU sooner.

That task fell to Gloria Cavazos, a speech language pathologist, Monday.

It is a delicate task.

“It’s scary, because you don’t know how the baby is going to react, because you don’t know how the baby is going to react,” she said. “But once you do it more and you get to know who she is — the babies, they all have different personalities — so you kind of know what to expect.”

Cavazos raises the top from Rebekah’s incubator. Rebekah doesn’t much care for this. It’s a touch warm in the unit for you or I; for her, it’s a little chilly. She can hear the beeps, too, and doesn’t care much for those.

Next Cavazos delicately arranges her patient, straightening Rebekah out in the blankets and squaring her improbably small legs, soothingly talking to her patient to comfort her.

A colleague gently cradles Rebekah, simulating the sort of pressure she would have felt in the womb.

Cavazos occasionally shifts her attention to a monitor nearby, waiting for Rebekah’s vitals to stabilize enough to complete the procedure.

“The noise, the light — it’s a lot for them to process,” she said.

In theory, Cavazos would then take a syringe with colostrum or milk and place a single drop on one side of Rebekah’s mouth and a drop on the other.

No dice this time. Cavazos suspects Rebekah needs to use the restroom, and she’ll try again in half-an-hour or so.

It’s an awful lot of fuss over .1 milliliters of breast milk. Cavazos and the other women in the unit treating Rebekah Monday say it’s well worth it.

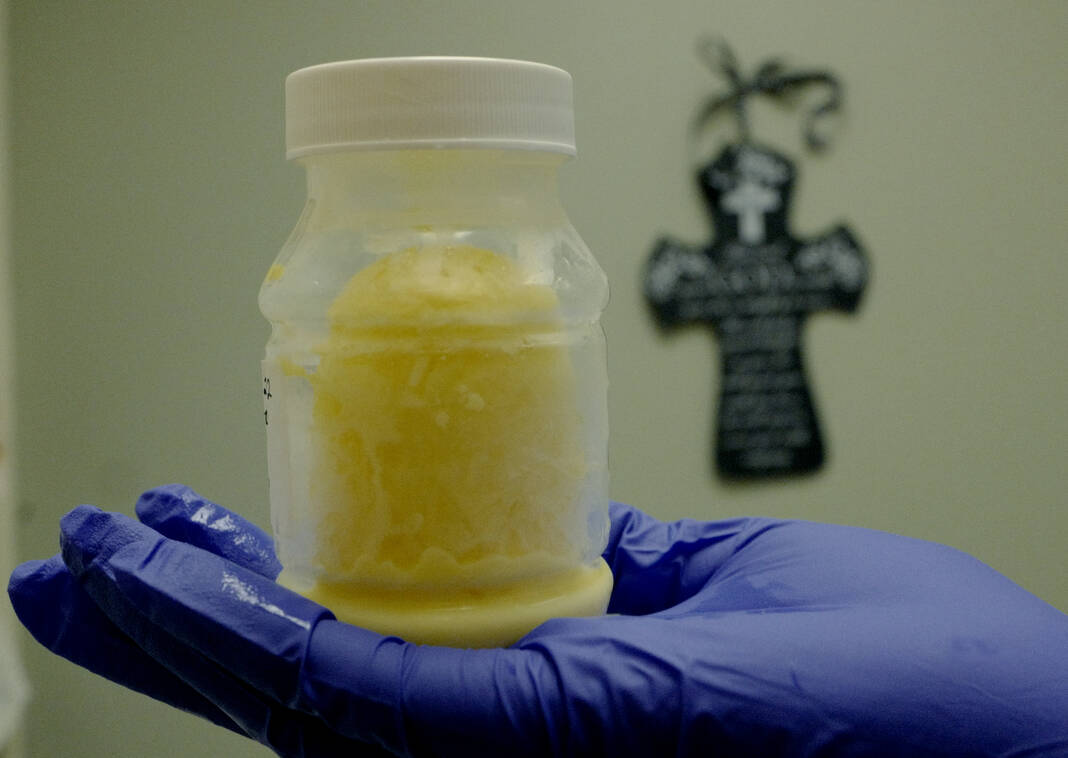

Gabby Reyna, a lactation consultant, holds up a container of colostrum: essentially a nutrient rich substance mothers produce before breast milk.

Yellow gold, Reyna calls it. It looks more like eggnog than milk, she observes admiringly.

“We all know — because there’s so many studies saying — that colostrum is super important, because it has special properties for the infants, especially for the micro-premature babies,” she says.

Reyna is a colostrum and breast milk evangelist. She talks about it passionately, and has good reason to.

When Reyna’s daughter was born 18 years ago with Type-1 Diabetes, doctors gave her a laundry list of issues she may face.

Reyna’s daughter didn’t, ultimately, face those issues; now she’s preparing to send her daughter off to college, to an Ivy League school.

Reyna attributes the success to breastfeeding.

“All the stuff they told me that might go wrong, somehow it got corrected with the breast milk,” she said. “So I’m talking as a mother, not really as a lactation consultant, and I want the mothers to just give it a try.”

The treatment, Reyna hopes, will extend the amount of months mothers breastfeed. She says it could have psychological benefits for mothers, along with physical benefits for their children.

“It’s going to improve their immune system, they’re digestive system,” Sarah Fryer, a dietician, said. “Improve the overall health by taking the mother’s milk.”

Rebekah is one of two babies in the unit receiving the treatment. The study team says they’re the only team in the Rio Grande Valley they know of providing the treatment.

Cavazos gently lowered the top of the incubator back over Rebekah Monday afternoon, before waiting for conditions for the treatment to look more favorable.

She’ll have a lot more drops to administer before any findings can be drawn from the study.

Reyna gets a call: there’s a mother downstairs who can’t get her baby to latch. She buzzes away, continuing her crusade for breast milk.

“There’s always something new in the NICU, every time,” she said. “Next day, something else.”