McALLEN – Jordan Gray has never taken too kindly to being told she cannot do something.

When she was just a year old, she indicated to her dad that she wanted to try the pull-up bar after watching him work out. He lifted her up so her tiny hands could grip the bar and said, “I bet you can’t do a pull-up.”

“He said I started gritting my teeth, straining, turning purple, trying to pull myself up,” Gray said. “It’s my personality. I’ve just always been that way. The ‘you can’t do this’ statement has always been a trigger for me.”

Gray, 25, trains in the decathlon — a track and field event that combines 10 other events, all runs, jumps and throws — making it one of the most challenging endeavors in athletics. Although a latecomer to the sport, it is safe to say she is one of the elite decathletes in the world.

She holds the highest score of any woman currently active. She set the American record and has produced the third highest score ever recorded in women’s decathlon. She has even set a world record in the long jump, a decathlon event.

One might expect to see her compete in the decathlon for Team USA in this summer’s Olympic Games in Tokyo. But that will not happen. Why?

“I’m a girl,” she said.

The decathlon is not contestable for women in the Olympics — an event available for men for more than a century. Instead, women compete in the seven-event heptathlon.

Gray, who works as a coach for Orange Theory Fitness in McAllen, has engineered a campaign to seek change.

She created the “Let Women Decathlon” movement to compel the International Olympic Committee to add the sport. It is too late for this summer’s Games and appears too late even for the 2024 Games in Paris. The IOC announced its 2024 sports program in December. Inclusion remains a possibility for the 2028 Games in Los Angeles.

Her effort is picking up steam. National media like NBC Sports in addition to Olympic news outlets Inside the Games and Around the Rings have highlighted her quest.

There is grass-roots support too. On National Girls and Women in Sports Day (Feb. 3), she launched a petition to make the decathlon a women’s Olympic event. In less than eight weeks, it has received more than 16,800 electronic signatures – more than 350 per day.

Many signees have been fathers of daughters in sports who have thanked Gray “for fighting for her future because if she wants to do a decathlon one day, I want her to be able to.”

Meanwhile, Gray is back in training for a chance at this year’s Olympics. She competed in her first heptathlon in nearly two years last week in California. She took second place, totaling 5,725 points, against elite competition that included several heptathletes ranked in the American top 10.

“Her shot put was her best event, throwing over 14 meters,” Andy Eggerth, who has coached her for about seven years, said via text message. “She was solid but just a little out of form from the lack of competition. More competitions that are happening now will allow her to be back on point. But this is her third best heptathlon ever, so it’s good. We just have high expectations.”

With more excellent performances, she can qualify for the USA Olympic Trials set for June 18-27 in Eugene, Oregon.

IT STARTED WITH THE POLE VAULT

One might ask why the concern if there is an avenue for women to compete. It’s simple for Gray: She wants the opportunity to compete in the more-challenging event at the highest level.

“She’s definitely a focused, committed hard worker,” Eggerth said. “As far as athletes I’ve worked with, she’s one of the hardest working ones.”

Eggerth recruited Gray and coached her for five years at Kennesaw State in Georgia. Eggerth, now in his second year as Assistant Track & Field Coach for the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, still serves as her personal coach.

Gray grew up playing all kinds of sports in her athletic family but did not get introduced to track and field until she was 17.

In college, Gray understood there was a decathlon for men and a heptathlon for women. She did not reflect on it though until she noticed male track athletes practicing the pole vault which is not a heptathlon event.

“I remember sitting there one day and I was like ‘I really want to pole vault,’” she recalled.

Coach Eggerth was initially hesitant to allow it. There were practical reasons for this. Time spent on pole vault would be time taken away from focusing on multiple specialty events already on Gray’s plate.

In addition, participation in the decathlon was a dead end. There was no avenue for women’s decathlon — not in the NCAAs, the World Championships or the Olympics.

As Gray’s proficiency improved, however, Eggerth allowed her to pole vault.

“I knew it wasn’t an Olympic event right from the get-go,” she said. “(Changing) it wasn’t necessarily my goal. At first, it was just (a feeling that) I want to do this full thing. I feel like you’re forcing me to do half-court basketball.”

She wondered how it ever became that way.

“I started thinking, why do women even do heptathlon?,” she said. “Why is this a thing? I want to do the full decathlon. This seems kind of unfair. Why don’t I get to do these (extra) events?”

It really hit home for her after competing in the 2019 USA Track & Field Championships in Des Moines, Iowa. She and a male training partner both competed in the decathlon. USA Track & Field had put together the first stand-alone women’s decathlon national championship.

One month after shattering a 19-year-old U.S. record, amassing 7,921 points, Gray won again. However, there would be no encore on a global stage.

“We do the same workouts,” she said. “We do the same weightlifting. We do the same everything and he’s a decathlete. He went and got second place and he got to go to Doha (Qatar) for the world championships and I got to stay home and watch him on TV because I’m a girl and I’m not allowed to go. It didn’t matter that I got first place. Didn’t matter that I broke an American record (one month before). Didn’t matter that I got a world record in the long jump. Nobody cared. You can’t go. That alone was upsetting.”

COMPARING TWO EVENTS

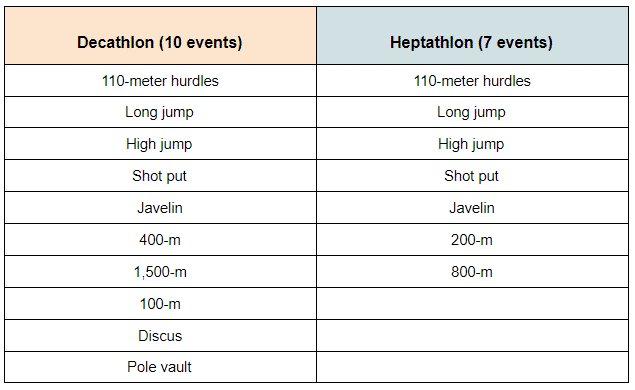

The decathlon consists of 10 events and the heptathlon has seven. The three additional events for men are the 100-meter sprint, the discus throw and the pole vault. In addition, two running events require longer distances for men. Men have 400 and 1,500 meter runs while women run 200 and 800 meters, respectively.

Athletes compete in these running, jumping and throwing events over a two-day period. Competitors accumulate points based on their performance in each event.

WOMEN IN THE OLYMPICS

The first modern Olympiad was in 1896, but women did not participate until the 1900 games in Paris. About 22 females competed in sailing, golf, tennis and croquet that year.

The decathlon became an event for men in 1912 and the champion is often synonymous with the “world’s greatest athlete.” Famous American winners include Rafer Johnson in 1960, Caitlyn Jenner (then known as Bruce Jenner) in 1976 and Ashton Eaton in 2012 and 2016.

The inaugural Olympic decathlon gold medalist was also an American. Jim Thorpe, who played in the early days of the NFL and who was later voted the Greatest Athlete of the first half of the 20th century, won in 1912 in Stockholm, Sweden.

A few events in women’s athletics (the European name for the sport of track and field) were added in 1928, but there was no decathlon or even heptathlon for women. Before the heptathlon, there was the five-event pentathlon, an Olympic event from 1964-80 (not to be confused with modern pentathlon which is not part of track & field). The heptathlon has served as the pinnacle for women in track & field since the 1984 Games.

AGAINST ALL ODDS

Curiously, World Athletics (the sport’s governing body, formally known as the International Association of Athletics Federations) approved scoring tables in women’s decathlon in 2001. However, women do not compete in it at the World Championships.

“It’s an existing event,” Eggerth said. “They don’t give women the opportunity to contest it. It’s odd.”

Gray has heard many arguments against women’s inclusion in the decathlon; some more exasperating than others.

They include women cannot do it. Women do not want to do it (a true sentiment among some professional heptathletes who do not want to train for additional events at this point in their careers). Women are not good at it. Poorer nations do not have the infrastructure and the crème de la crème – it would be difficult to schedule.

“You have to keep yourself so composed and you have to deal with people,” she said. “You have to answer their questions as if they are valid questions or they will just shut you down and call you crazy.”

As an individual, there is no avenue to meet with the IOC, but other organizations can go to bat for her. She recently met with representatives from NACAC (the local continental confederation, one of six geographical associations of World Athletics) to share her story.

She is not giving up, whether on the track, for her cause or at the pull-up bar.

To view her petition, visit letwomendecathlon.org

BY MARK MAY