As a migrant camp was dismantled Saturday afternoon in Matamoros, migrants leaving the site to head to a shelter handed blankets, buckets and other belongings over the fence to other migrants who arrived days ago, ready to take their place and try their luck on the Mexican streets waiting their turn to request asylum in the U.S.

Just a week ago at the same location, singing and celebration could be heard as nearly 700 migrants living inside were anticipating their reprocessing into the U.S.

By Friday, the grounds lay still and quiet. A few were left behind.

They are ineligible to be reprocessed under the Biden administration’s first phase of rectifying damage done by the previous administration’s policy, which placed nearly 70,000 in former President Donald Trump’s Remain in Mexico policy. Only those with active cases in immigration or appellate courts qualify to be reprocessed into the country, about 26,000. Those denied are still in Mexico or back in their home countries.

Iris, a 26-year-old El Salvadoran woman, was one of the remaining 72 ineligible migrants at the camp. Her name is withheld for safety concerns.

Migrants who lived since 2019 on the edge of the river where corpses surfaced, rats crawled, snakes slithered, and cartel groups visited frequently found safety in numbers and community. Leaders representing each country helped organize and strategize their fortunes.

By Friday, those systems of survival were dismantled along with their shelter, bathrooms, water and electricity sources. As night fell upon the unraveling settlement, the group huddled. Their phones, their only connection to loved ones, were losing their charge.

“We’re planning on staying, because if we leave they’re going to forget about us,” Iris said, wringing her hands and sitting by the fence under a streetlight. U.S. authorities only planned to bring back those who have active cases under the Migrant Protection Protocol, about 25,000.

Just feet away, on the other side of the fence separating the international bridge from the camp, about 20 migrants, mostly Hondurans, sat in the plaza. Children on laps of mothers sitting on public benches and concrete waited for their chance to enter the U.S.

One mother traveling with her children said she arrived the previous night, and in the span of a day, they were nearly kidnapped in Tamaulipas.

Immigration officers were trying to disperse the group all day, according to the Honduran migrants. They offered them shelters, which were packed, or sent them away from the bridge.

“I’m not going, even if I have to stay on the sidewalk, I’m not leaving,” a mother carrying a toddler in her arms said, echoing Iris moments ago.

That night, the group slept behind the immigration offices, opposite from Iris and the others in the camp. A fence and a policy differentiated them, but volunteers, the following day, would find their needs were the same.

Sidewalk Schools co-founder Felicia Rangel-Samponaro and Fran Schindler drove from Brownsville to Matamoros at 10 a.m. Saturday. Sidewalk Schools is a nonprofit working along the border.

“It’s always a rollercoaster of up and down, always,” Rangel-Samponaro said. Saturday would pose a different challenge.

The group of Hondurans who slept on the street was unexpected. They represent a growing group of people arriving at the border, hoping to enter the U.S.

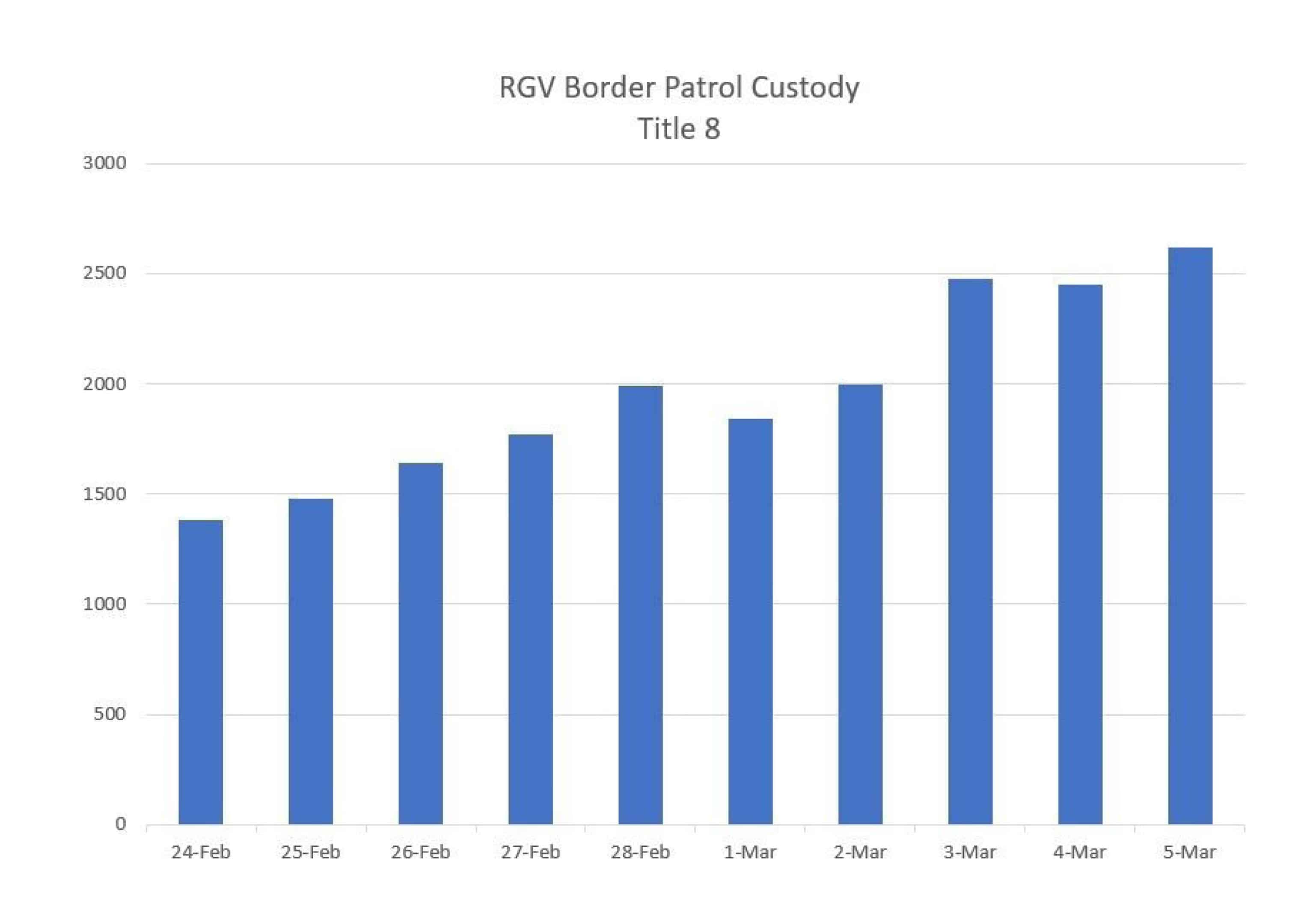

According to records obtained by The Monitor, the number of people in custody, like the Hondurans who are requesting asylum, is on a steady upswing in the Rio Grande Valley.

On Feb. 24, agents had almost 1,380 in custody, waiting to either be transferred to a detention facility or released into the U.S. with a notice to appear at an immigration court at a later date.

By March 5, that number doubled to nearly 2,620.

As of Saturday, about 3,000 people were in custody. That included those waiting to be sent into the U.S. or those to be sent back to Mexico, under a government code known as Title 42.

The holding capacity by U.S. Border Patrol in the Rio Grande Valley is greatly reduced from the total capacity seen in previous surges, like 2019.

During that time, the holding capacity at the central processing center was close to 850, and the overall capacity from the combined use of the center with Border Patrol stations and additional stations was about 2,000 people, according to reports shared by the agency then.

Currently, the central processing center is closed. Though an additional temporary site was set up in Donna, COVID social distancing restrictions, court decisions and policies meant to protect the safety of migrants have adversely affected the holding capacity.

Resources are lacking on the Mexican side, too. Organizations like Rangel-Samponaro’s are working to address those needs.

On Saturday, Rangel-Samponaro and Schindler drove to a grocery store and packed about $250 worth of bread, ham, cheese, chips, diapers, baby formula and sanitary pads into their carts and drove back to the Hondurans.

As the migrant families ate, other non-governmental organizations were allowed into the camp to talk to the remaining MPP migrants. They convinced them that their only safe choice forward was to leave the camp and enter a shelter.

Some left walking. Most boarded tour buses that took them to a shelter in the city.

“It’s very difficult to make this decision, but they’re promising us that we will ultimately go with our relatives in the U.S.,” Iris said, in a defeated tone as she recorded her impressions over a WhatsApp recording.

Rangel-Samponaro and Schindler went to the grocery store again and delivered meals to the migrants at the shelter. More trips are expected.

“Tomorrow we travel to Reynosa, our eighth city, to set up the school and give out more donations to the people who live outside on the bridge over there,” she said, referring to migrants waiting to claim asylum.

As the sun went down at the migrant camp Saturday, discarded medicine bottles, baby socks, unmatched shoes, a broken doll, torn tarps, and other debris littered the site.

Among the items left behind of Remain in Mexico, a green journal with a two-page entry documented what many felt as they arrived in 2019, and what many may experience as they arrive on the same border only to be sent back to Mexico under a different policy.

“My story in Matamoros, Tamaulipas,” the first page read. “I arrived disillusioned after failing to enter the United States, because it was my dream to go to my relatives and they truncated them by sending me to Matamoros to sleep on the ground. It was so humiliating what I’ve lived.”

Related

After 2 years in limbo, migrants seeking asylum in US finally cross from Mexico