McALLEN — The trial against two men accused of participating in an intricate scheme to defraud the city of Weslaco out of millions of dollars got underway in federal court here Tuesday.

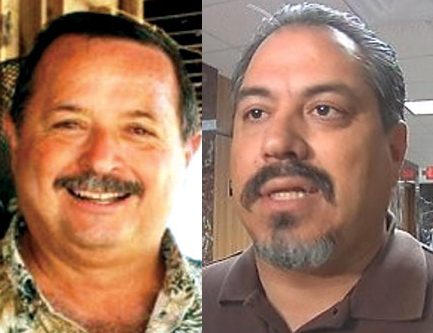

The case against Arturo “A.C.” Cuellar, former Hidalgo County Precinct 1 commissioner, and Weslaco businessman Ricardo “Rick” Quintanilla, comes more than three years after prosecutors began unveiling a host of criminal charges related to the rehabilitation of Weslaco’s overburdened water treatment plants.

And from the outset, the government is making clear what they think this case is about — massive public corruption that the conspiracy’s participants worked hard to obscure.

“This is a case about corruption and concealment,” William J. Gullotta, a trial attorney with the Justice Department’s Public Integrity Section, said as he addressed the jury on behalf of a cadre of government prosecutors.

“The defendants wanted a piece of the more than $40 million that the city of Weslaco was spending” to rehabilitate the city’s ailing water and wastewater plants.

OPENING STATEMENTS

Gullotta provided an overview of the case the government will be making against Cuellar and Quintanilla over the next two weeks.

He touched on how Weslaco was in desperate need of addressing yearslong issues at its water plants after having received a litany of warnings, citations and threats of fines from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

The city had put off the issue since TCEQ first began issuing capacity warnings to the city in 2004.

But, as the tenor of the state regulator’s warnings began to grow ever sharper, some members of the Weslaco City Commission — along with a select group of interested stakeholders — began to see TCEQ’s clarion calls as a way to create their own personal cash cow.

Cuellar and Quintanilla, the prosecutor alleged, became middlemen in a bribery scheme between the commission’s majority faction — led by longtime commissioner John Cuellar — and the firms the city would go on to hire for the project.

John Cuellar, who is A.C. Cuellar’s cousin, would go on to steer votes in favor of three firms: Massachusetts-based CDM Smith, San Antonio-based Briones Engineering and Consulting, and McAllen-based LeFevre Engineering and Management Consulting.

He did so with the help of fellow commissioner Gerardo “Jerry” Tafolla.

And at the heart of the conspiracy was Leonel J. “Leo” Lopez Jr., then the municipal judge for Rio Grande City.

“Leo Lopez was the mastermind of this bribery scheme. … CDM and Briones… wanted the water treatment plant contracts and they paid Leo Lopez,” who then orchestrated the distribution of bribes to Weslaco public officials, Gullotta said.

As the conspirators grew their plan, so, too, did the estimated costs of repairing or replacing Weslaco’s overburdened water infrastructure, prosecutors said.

“The estimates increased multiple times from hundreds of thousands of dollars to more than $40 million,” Gullotta said.

The prosecutor repeated his refrain: this was a scheme of “corruption and concealment,” he said.

DEFENSE’S OPEN

But the defense had a different view of what had happened.

As A.C. Cuellar’s defense attorney, Carlos A. Garcia, put it, his client hadn’t done anything wrong.

Instead, A.C. Cuellar, who owns several construction and concrete-related companies, had simply acted as any shrewd businessman would — and also as any close family member would.

Garcia detailed the story of A.C. as a man deeply devoted to his family’s legacy — one founded by the Cuellar family patriarch, Dr. Armando Cuellar.

The doctor had always taken care of his family, and in that vein, A.C. had wanted to take similar care of his cousin, John.

At the same time, A.C. Cuellar, as a businessman, tried earnestly to serve as someone who could facilitate introductions between out-of-town construction firms and local potential clients.

As for how his client and the other alleged co-conspirators became ensnared in a criminal case, Garcia chalked that up to overzealous FBI agents looking to bag law enforcement trophies at almost any cost.

“Agents come from out of town. They come here out of some sort of hardship… looking for that trophy,” Garcia said.

And in the course of pursuing their prey, Garcia all but accused the federal agents of coercing admissions of culpability from the co-conspirators who have pleaded guilty since 2019 — including John Cuellar and Jerry Tafolla.

“They pled guilty after the government squeezed them like a lemon,” Garcia said.

FIRST WITNESS

After the two sides presented their opening arguments, the government called its first witness — Elizabeth Walker, who served as Weslaco’s city secretary and, for a brief stint, as interim city manager.

Walker’s testimony was deliberate and detailed as prosecutors walked her through the minutes — or official records — of 14 public meetings held by the Weslaco City Commission between March 2008 and September 2014.

Walker read the descriptions of various votes the commission took in relation to the water plant rehabilitation — from when the approval of the first engineering studies, to the approval of contracts and their amendments.

And at each point, Walker read how John Cuellar or Gerry Tafolla were instrumental in those approvals by making the motions themselves, seconding them, or voting for the items.

Those votes included approving hiring CDM and Briones, as well as setting the project’s “guaranteed maximum price.” They also included approving an amendment for a piece of automation technology that raised the cost estimate by more than $3 million.

Most notably, prosecutors asked Walker to recall a conversation she had via telephone with the principal of LeFevre Engineering, Richard LeFevre, after the city — concerned that something was amiss — had stopped paying the firms associated with the project.

At the time, Briones Engineering had hired LeFevre’s firm as a subcontractor. But, when the city stopped paying Briones, he, in turn, had stopped paying LeFevre.

As a result, LeFevre approached the city for payment. When Walker explained to him that he would have to pursue Briones for payment, LeFevre made a comment that Walker said she remembered “to this day.”

“Elizabeth, you have to know that this water treatment plant is a beached whale and everyone is feeding off the carcass,” LeFevre had told her, Walker said.