By Josh Ellerbrock, AIM Media Network

LIMA, OHIO — Just over the horizon, Election Day looms.

But it’s the day after that matters more.

Both the Trump and Biden campaigns have predicted what the country will look like if the other ends up taking the White House, and the political rhetoric foresees plenty of doom.

The country will still need to move forward regardless, and either way, it’s going to be a rocky road

How did we get here?

According to Robert Alexander, the American voter is being sorted.

The political science professor at Ohio Northern University has been watching this last year play out in its strange ways, and while plenty of questions remain unanswered about our current political situation, he can provide some context to where the voting electorate has arrived after decades of politicization.

“A lot of that sorting started in the 1950s and 1960s. It really began to happen with the disintegration or the change in the Democratic party in the South, or the rise of Dixiecrats,” Alexander said. “The southern Democrats would be considered Republican today.”

In the years following, political lines deepened as more and more issues became two-sided and often ideological. As the federal government grew and federal law expanded, issues like abortion, immigration and gun policy became major national talking points for the political parties.

Meanwhile, the national media and 24-hour news networks began to rely on two-sided conflicts to generate ratings. An enraged and passionate television watcher is more likely to keep coming back for more, and the feedback loop got bigger and bigger as entertainment journalists began to rely on talking heads, pundits and shows like Crossfire, which pitted angry policy wonks yelling hyperbole at each other.

Eventually, the differences between the two parties became deeply ideological, then cultural, then geographical.

Soon enough, politically active primary voters began to cast ballots in favor of ideological purity instead of focusing on particular policies, and politicians evolved to grab those votes, Alexander said. The gap between the two parties widened accordingly.

Today, confluences of social media, hyperbolic rhetoric, targeted foreign misinformation campaigns and racial animosity has only increased those trends.

As for many Americans, they’ve had to follow along despite never really being all that interested in politics. Alexander pointed to historically low election turnout rates and voter registration rolls as proof. Even in the current hyper-partisan era, 40% of Americans still identify as independents.

“Most of us are not red or blue,” Alexander said. “Most of us are purple, but we’re forced into choices that are red or blue.”

Today, fights between Republicans and Democrats are now “winner-take-all” affairs with political norms on the chopping block if it’s politically convenient. The most recent example is Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell blocking a year’s worth of judicial appointments — and Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland — from getting a hearing in the Senate. The result is further backlash from the Democratic Party, which is considering expanding the court.

Can one party “win”?

A big problem with the winner-take-all approach is that the loser gets nothing, even if the losing side makes up 49% of the electorate. Over time, it creates resentment.

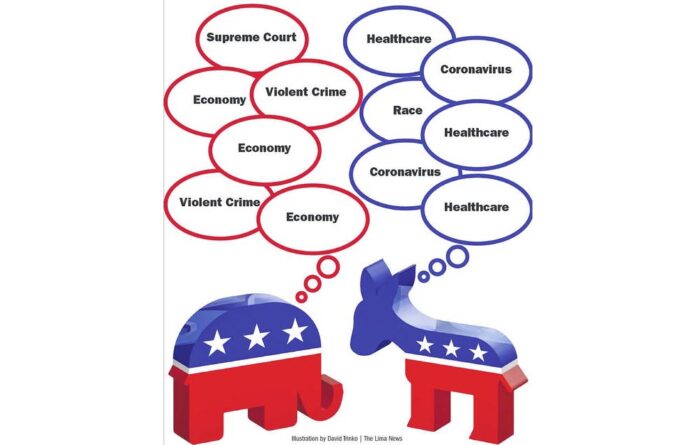

A review of Pew data examining the largest issues of the presidential elections shows how some of that resentment has shaken out over the last decade.

Take the immigration issue as an example. Back in 2008, 63% of Republicans considered immigration to be very important when considering their presidential vote. After eight years of President Barack Obama, though, that number jumped up to 79%, and it became one of the primary features of then-candidate Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign.

By 2020, Republican voters are largely happy with the direction Trump has taken immigration, and that percentage has dropped back down to 62%.

“He followed through with most of his promises,” Jane Seiling, who donated to Trump’s campaign said. She’s hoping immigration gets some renewed focus if he wins.

“People have forgotten about the southern border. I’d like to see the wall finished and see what they can do about stopping people from coming over the border,” she said.

As for the other side of the aisle, Democrats are going into this presidential election resentful of many of Trump’s actions in office. Three of the top five issues for Democratic voters this election cycle — healthcare, climate change and racial inequality — have largely been dismissed by his administration, and the White House has taken steps to dismantle past Democratic initiatives in these areas.

“He says he’s got this great health-care plan, but it’s just a bunch of smoke and mirrors from Trump,” Rick Siferd, who donated to Biden’s campaign, said.

He’s concerned that conservatives are working to ditch the Affordable Care Act in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, which would remove people from health-care rolls.

“I am hoping and praying that Biden wins, and it’ll be a cold day in hell before I vote for a draft dodger,” Siferd said.

Considering that the polarization between the two parties is widening, each swing to the other side leaves vast swathes of the electorate more concerned than before. In fact, many political commentators have looked at nationwide resentment in rural areas as one of the reasons Donald Trump became such a strong political figure, and they expect the same sort of political resentment — now felt by cities and coastal areas — to fuel a high turnout election this year.

A way out

While the problem is complicated, Alexander said there may be pathways to return politics to a more even keel.

One such option is fixing the types of governmental systems and voting practices that encourage two-party politics to emerge.

“It’s really about structural change more than anything,” Alexander said.

At the heart of the problem is representation. Due to how the government is organized, the strength of each American’s vote differs widely based purely on where a voter lives. The electoral college is the most obvious example of this. Because only a few states have the tendency to flip between red and blue, they often receive the most attention, and other states have a reduced say in who actually takes the White House.

This representational problem, however, also bleeds into other branches of government as well. Ohio is a great example. Three-quarters of Ohio’s Congressional delegation are Republican, while just over half of its registered voters lean to the right, according to Pew Research Center numbers.

A potential fix, Alexander said, is to move to practices like ranked choice voting or multi-member districts that can help capture the influence of those in the political minority.

The problem, however, is making that conversation palatable to the average American, and polarization is actively fighting against the discussion. Right now, such changes are largely seen as Democratic initiatives (or third party), but Alexander said Republicans could get on board if there’s another sea change, and they end up performing in 2020 as well as current aggregate polling predicts.

A second option along the representational route is increasing civic engagement. In the immediate wake of the death of George Floyd, the nation watched as cities filled up with crowds enlivened and angered by the current racial inequalities in the country. Since then, the political conversation has only grown more complex and heated as the situation has evolved, but many groups across the United States have worked to catalyze that energy into higher turnout at the polls.

Arisha Hatch, executive director of the Color of Change PAC, said her group has been focused on engaging with voters this election season and helping them participate in the democratic process of voting. Like many other political action committees, the goal is to get those of like-minded views elected to political office and hopefully elevate the conversation around the issues.

“I think we obviously live in a very polarized country. In some ways, this two-party system has incentivized focusing on the places that we don’t agree rather than the places that we do.” Hatch said. “It results in a conversation in which we’re not speaking the same language.”

The debate around the current “defund the police” initiative is representative of that, Hatch said. When voters of different political leanings actually have a conversation instead of reacting to a politically-loaded phrase, headway can be made.

Other PACs have seen similar results when trying to find common ground in the chasm separating Republicans and Democrats. This past year, the Ohio Environmental Council Action Fund — which focuses on state environmental issues — ended up endorsing both Democratic and Republican state representatives primarily based on work performed around a shared need, clean water.

“We’ve taken some pretty bold endorsement decisions to endorse several Republicans in very tight races because they did some amazing work,” Fund President Heather Taylor-Miesle said.

Sarah Spence, director of climate programs at OEC, said her discussions in the conservative sphere have focused primarily on market change and innovation rather than some of the more loaded-terms when discussing energy policy. Spence, who leans to the right, said even small changes like switching out “environmentalist” with “conservationist” — and vice versa — can help push the conversation forward to a more solution-focused discussion.

The big question of the current political era, however, is if the average voter can have those same sort of solution-focused discussions about their own political processes. No matter who wins in November, that answer won’t be known until long after the votes are counted.