SAN BENITO — On an early morning, Magda Bolland, executive director of the La Posada Providencia shelter in San Benito, arrives at the small cluster of houses to start her day. The morning is bright and warm. Fog still recedes into the surrounding fields, lit up by bright sunlight.

She is almost immediately greeted by a young boy, who calls her name as he emerges from the playground. The boy informs Bolland that he needs help cleaning the space before disappearing back around the corner.

Roughly five buildings on a corner of land in rural San Benito house asylum seekers from all over the world who have been released from Border Patrol processing with no family in the United States, no sponsors, and nowhere to go.

Founded in 1989 as a sponsored ministry of the Sisters of Divine Providence, La Posada is the only long-term shelter along the U.S.-Mexico border.

“We recently had a man from China who stayed with us after being released from detention in California. He was sent to us because there are no other long-term shelters for asylum seekers in California, Arizona, or New Mexico,” she said.

“The only similar one I’m aware of is Casa Marianella, in Austin. We sometimes coordinate with them.”

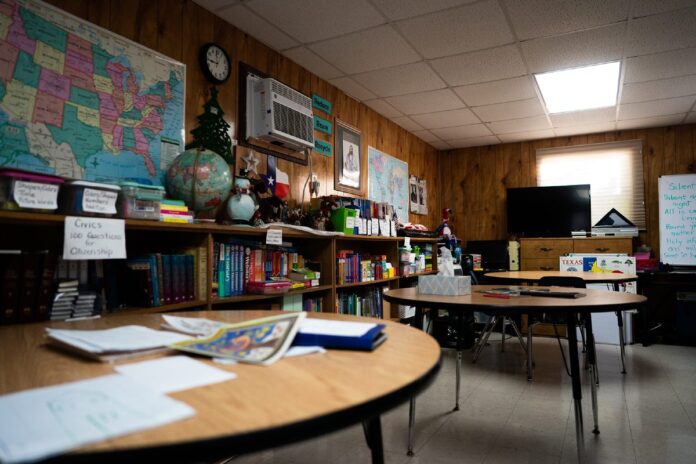

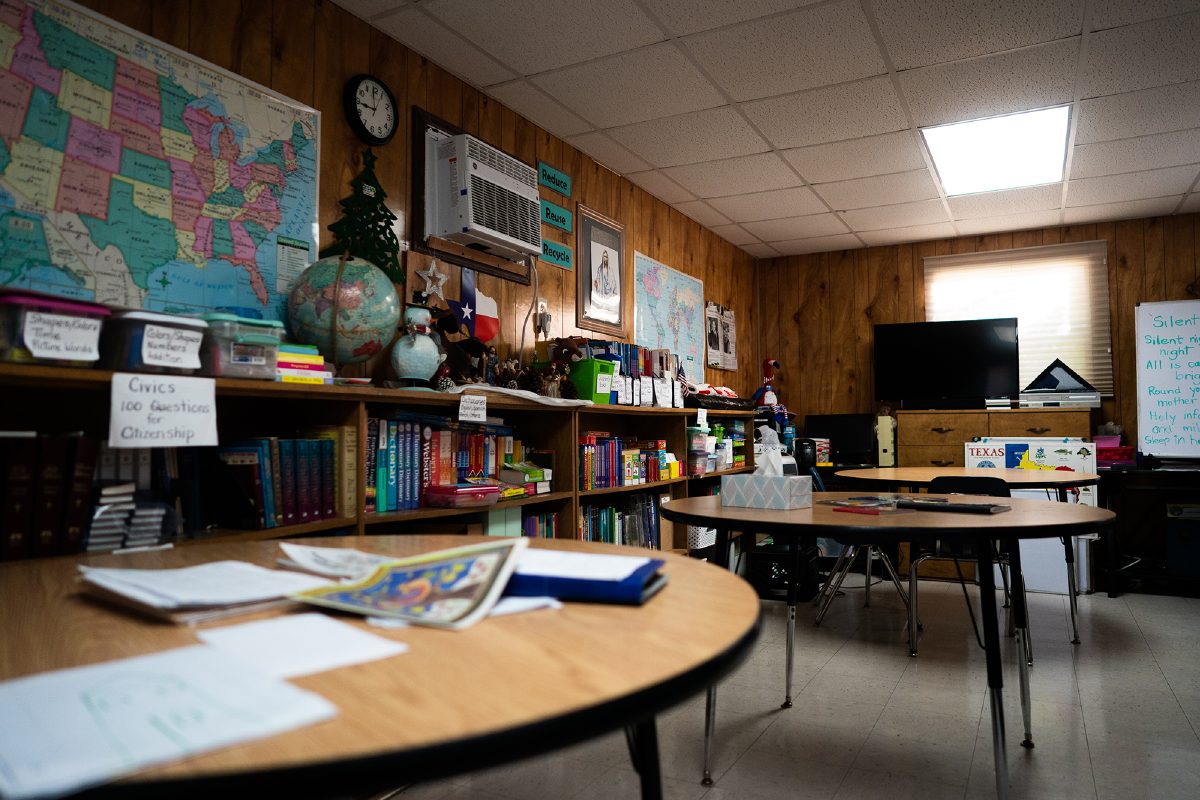

The shelter moved to its current location in San Benito in 1995. Bolland opened the door to a metal trailer constructed with donations that now houses a mobile ESL classroom. Courses are held daily for the shelter’s roughly 16 to 18 residents.

The space, put together by a nun who works on staff, is complete with three tables, a television, encyclopedias, books, and maps of the United States and the world.

The small room also houses support group and therapy sessions led by Dr. Selma Yznaga, a professor of counseling at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley who specializes in assisting immigrants.

In 2018, the shelter formally became a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, from which it now accepts donations to maintain facilities and stay in operation. The shelter celebrated its 30th anniversary last year.

Bolland shared that on Dec. 1, one of the founding Sisters spoke at a benefit where she specified that the date marked the anniversary of when the first client walked through the doors in 1989.

As Bolland described it, Central American migrants fleeing war were transiting the Valley in large numbers in the ’80s and ’90s. Groups of volunteer attorneys worked to release migrants from detention. Upon posting bond, a small minority of those released had no other option but to sleep in legal offices and bus stations.

La Posada was founded by a nun from Pittsburgh who saw the need for a humanitarian effort sheltering migrants transiting the Valley who had no long-term living situation to get back on their feet.

“One of the sisters went back to Pittsburgh and told them, ‘We need to do something. There are people living in bus stations and cubicles.’ With very little resources, they came down here and rented a house,” she says.

The shelter has been taking in those in need ever since. In early December, Bolland helped coordinate the intake of Mexican asylum seekers who had been processed and granted entry by Border Patrol and dropped off at the Brownsville bus station in the middle of the night.

The director says that the shelter is just beginning to encounter people who were stuck in Mexico as a result of the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP).

“Recently, a woman from Nicaragua walked to our door. She’s was five to six months pregnant. Two of my key staff members were meeting with UNHCR. So I was understaffed. She had all of these papers. She was telling me that she had to be at court on Monday at 4:00 a.m. and that she needed to go back to Mexico,” recalled Bolland.

“It took me a while to figure out what was going on. I had never encountered this before. She had been granted parole for a year. But her boyfriend, the father of the child, was still in Mexico. She had his Notice to Appear (NTA). It’s shifting the way we work.”

Bolland consulted with an attorney and ended up bringing the paperwork to the man in Matamoros, her hometown, on the way to a Christmas party. The shelter coordinated a taxi to take the woman to the hearing. Afterward, she got on a bus and left for Florida.

The shelter also sees lots of 18-year-olds who have aged out of the custody of the Department of Health and Human Services. This time of year, Bolland says the shelter tends to see asylum seekers from African countries.

Inside the main building, which houses staff offices and a kitchen, a group of women gathered at the table for breakfast. They smiled and greeted Bolland, who was able to communicate with the current guests as they’re Spanish speakers.

This is not always the case, and staff members sometimes get by using translation devices. Bolland says the process can be extraordinarily frustrating for guests unable to communicate with staff.

“Recently, a woman came through from a country in Africa. She spoke French. I learned French in high school, but not much. The moment I was thrown into that situation, I was able to hold basic conversation with her. She was so happy. We also use technology, Google Translate,” says Bolland.

The director cites another story where a man from China recently came through the shelter. He had spent months in detention with migrants primarily from Central America and knew a bit of Spanish as a result.

“We communicated through a mixture of English and Spanish. He actually knew and was friends with some of the other residents. He met them in detention. In other cases, it’s very hard for these people. They’re unable to share their stories.”

According to a chart provided by Bolland, the shelter served 242 clients between July and December 2019. Of those clients, the shelter saw residents from Angola, Cameroon, China, Congo, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Eritrea, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Mexico, Nicaragua, Russia, Sri Lanka, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and the United States.

Ultimately, Bolland says that the shelter’s mission is to provide clients stability in a way that facilitates healing. She cites this as the most rewarding aspect of her work.

“People come here and they’re going through a hard time. You can see it. The parents have this look — like their body is there, but emotionally, mentally they’re somewhere else. And the children, of course, are upset. They want attention, a hug, and warmth. But the parents are just so broken that they’re not able to do that.”

“If they stay for a few days, you can see them back to normal. The kids stop crying all the time and they’re smiling, they’re laughing, they’re playing. And the parents understand that they are safe now.”

The shelter is on track to meet its budget for the first time in years. Those who wish to help can sign up to volunteer or donate via La Posada’s website, lppshelter.org, or through Facebook.