There’s no telling everything history buffs or genealogy researchers could learn if they were able to easily thumb through the historic civil and criminal cases of Cameron County.

And they will get their chance to find out soon.

The District Clerk’s Office is spending about $243,000 from its technology fund to preserve and digitize 55 boxes of case files from 1850 to 1917.

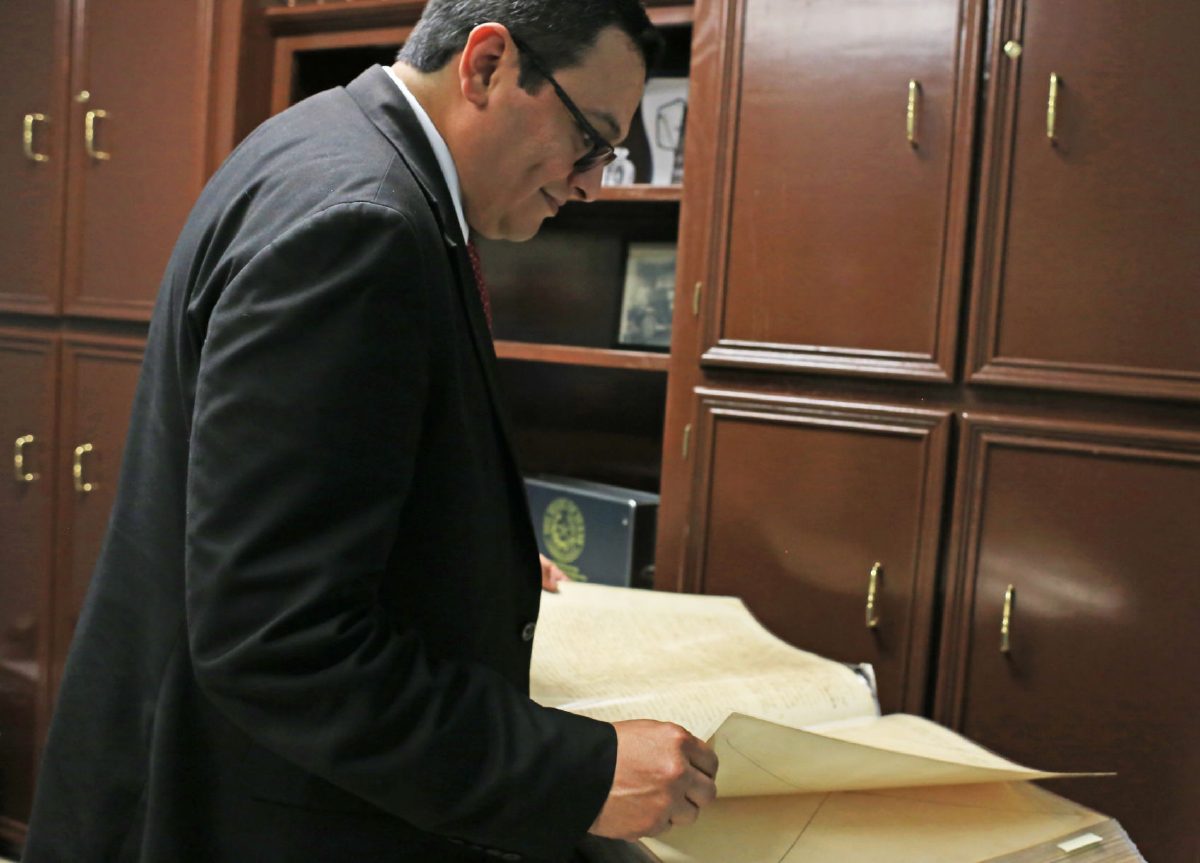

Cameron County District Clerk Eric Garza said the expenditure was made using court document filing fees his office has saved over four years. It includes an estimated 156,800 pages to be preserved by Dallas-based Kofile Technologies and is part of an ongoing records management plan.

“ We work to make the files accessible to the public, whether they were filed two days ago or 100 years ago,” he said. As the documents age, he added, they will become more difficult to decipher.

Garza said there’s a high level of expertise and time involved in preserving the documents while ensuring they aren’t damaged further.

First, pages must have staples and tape removed, and be flattened. They will be scanned, microfilmed and placed in acid-free binders. The binders and microfilm will be sent back to the District Clerk’s Office.

Garza said any documents from before 1955 are considered historic. He made an exception for one file due to its high-profile nature: records from a 1960s case involving assassin Charles Harrelson, father of actor Woody Harrelson.

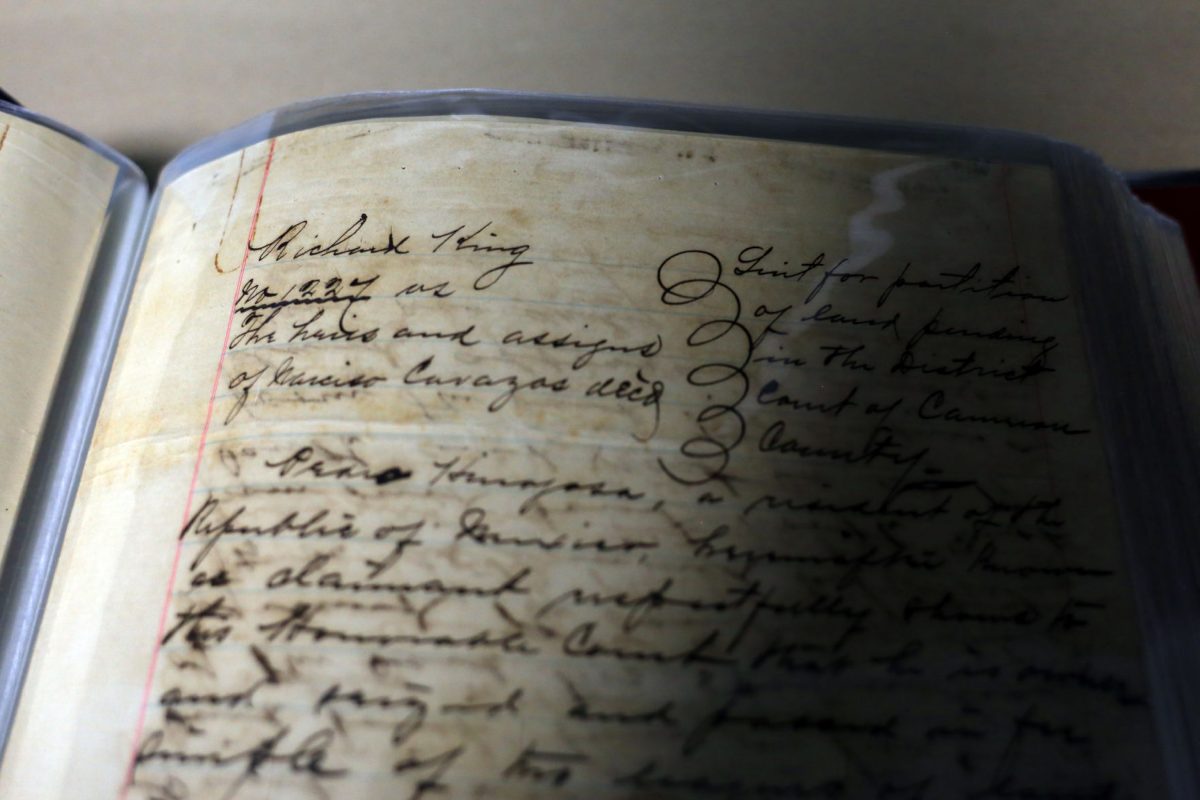

Among the most historically significant case files to have undergone the preservation process is King vs. The Heirs of Narciso Cavazos, which details the legal battle between the Texas cattle baron and the family of a Spanish land grant recipient over a vast swath of acreage. The case is mentioned by author David Bowels in his book “Ghosts of the Rio Grande Valley,” in which he writes that Richard King and partner Mifflin Kenedy won the case in 1881 and sold off land for massive profits.

The case files are an example of the treatment other historical records will get. Its yellowed pages, inked with neat cursive script, are protected by acid-proof plastic sleeves in a waterproof and fireproof binder.

Rick Cornejo, chief deputy district clerk, said people who believe they are decedents of the litigants — therefore entitled to land and mineral rights — still come looking for the documents. He recalled one woman who visited the office three years ago broke down in tears because she had nearly given up hope of finding the sprawling, handwritten family tree that’s part of the files.

Other cases paint a story of life in Brownsville near the turn of the 20th century. In 1914, one man received one year in county jail for assault with intent to kill. The same year, another was sentenced to two years in state prison for theft of a horse.

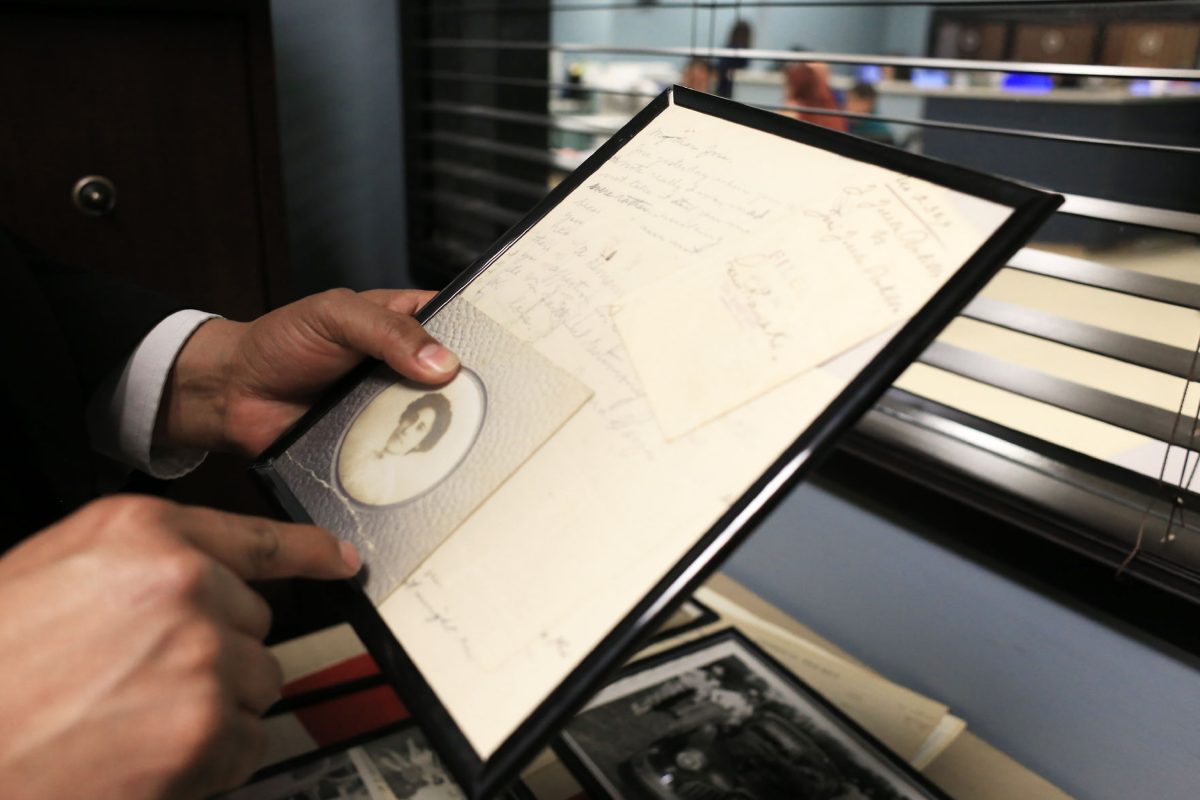

Case files also contain photos and other documents used as evidence during trials. Cornejo said letters with valuable stamps are stored separately.

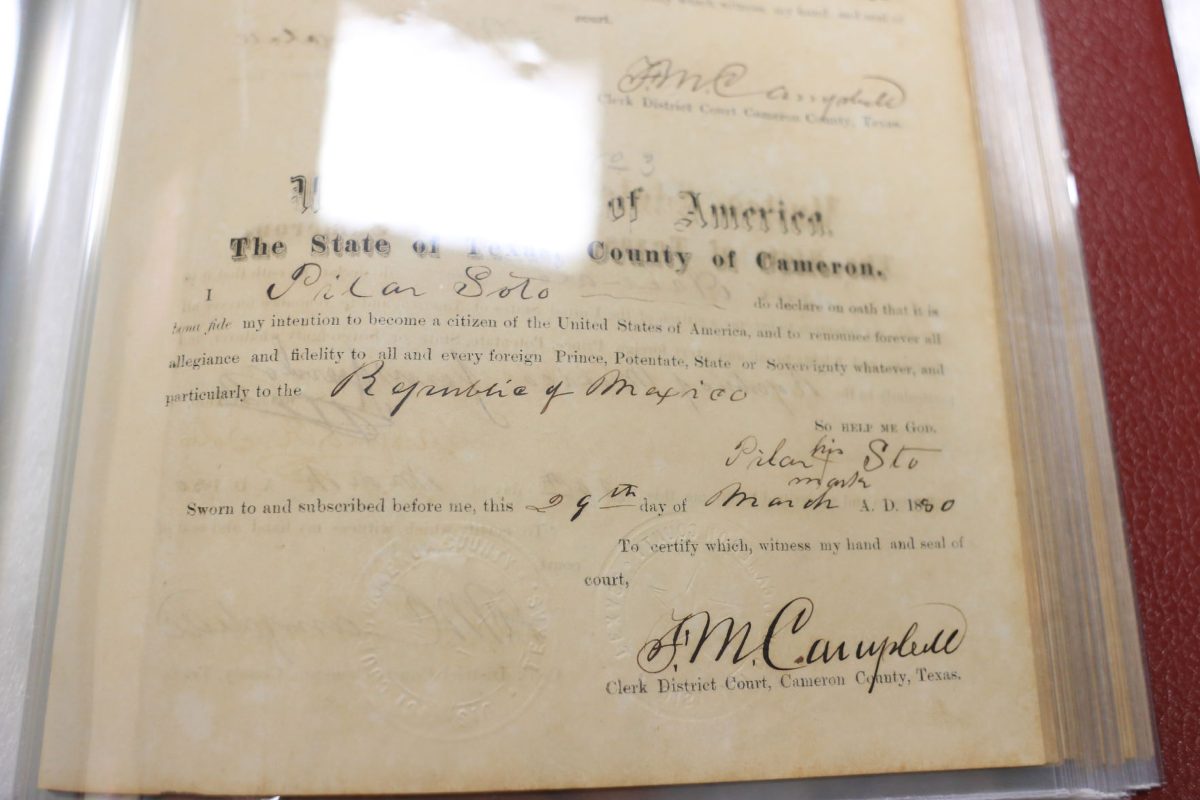

Historic naturalization certificates have undergone the protection process. Garza said they include naturalizations filed when people adopting children from Mexico simply had to meet the children at the middle of the international bridge and fill out the naturalization paperwork.

“ This is the history of each of our families,” Garza said. “Our grandparents forget or parents forget, but we want to know how we got here to Brownsville.”

About 90 percent of the documents have been sent to Dallas and will be returned in about two months, Garza said, but the public will be able to search, view and download images of the files before then.

Also, Garza is working to make the content of the files more easily searchable. He plans on launching a Wikipedia-like site that contains transcriptions of the documents. That system will be available in three to four months, he said.

His office will ask for volunteers who can help decipher and transcribe what’s written in the files, he added.