BY NORMAN ROZEFF

Counties in Texas, more often than not, are named after an area’s favorite or notable son and many times by its pioneer founder. The exception is the one county in Texas named after a woman. This is Angelina County, which is named after a Hasanai Native American woman who assisted early Spanish missionaries and was named Angelina by them.

The story of Cameron County’s namesake is a long and interesting one. Readers will be surprised by the fascinating history involved. Ewen Cameron, who was born in the Highlands of Scotland in 1811, came to Texas as a 26-year-old in 1837. He carried with him the genes of numerous Scotsmen and Scots-women who had validated themselves over time as both great fighters and leaders of men.

Such of his documented ancestors go back to the early 1600s and included a number of Ewen Camerons from whom his parents selected a name that would signify bravery and commitment. These included Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochial, the 17th Chief of the Cameron Clan and Sir Ewen Cameron who was a supporter of both King Charles I and his son, King Charles II. This latter Ewen had distinguished himself in fighting the English after it invaded Scotland in 1652.

The Ewen Cameron of Texas fame was an impressive looking individual. At 6-foot 2 in height in his moccasin footwear he stood ramrod straight and weighed in at over 200 pounds. He had dark hair, gray eyes with heavy brows and was smooth shaven.

Once in Texas Ewen joined a band of young daredevils who made a living rounding unbranded cattle and selling them in San Antonio. They were, in effect, the first Anglo cowboys borrowing much from their Vaquero predecessors. They able to pursue this work because, the area was largely unsettled by natives of Mexico and large swaths of land were yet to be occupied by newcomers. This left many cattle and wild horses to be rounded up and sold to new American settlers.

The matter of territorial rights was not settled by Texas independence. San Antonio, in fact, was invaded in 1842 by the Mexican Army. A year before in 1841 Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar had approved an ill-fated invasion of New Mexico in June led by General Hugh McLeod. This force was handily defeated and 320 men of the of the expedition captured and sent to Mexico City after which the United States government had to intercede to negotiate their release the following April.

When Sam Houston succeeded Lamar as president of the Republic of Texas he called out regiments of the Militia and asked for Volunteers. When two companies of the latter were organized in Washington County Ewen Cameron was elected as captain of a company. All these soldiers mustered near the Old Mission Concepción of San Antonio in November of 1842. General Alexander Somervill, age 46, was appointed their commander by Houston. What then transpired was to be a sad chapter in Texas history.

The organized contingent marched to Laredo later in that same November month. They soon captured this city. Now with little to do some soldiers soon left for home. “Houston’s instructions to Somervell were to continue the invasion only if circumstances assured a reasonable chance for success. Because almost one-third of the participants returned home soon after the capture of Laredo, Somervell determined that the remaining force was not strong enough nor did they have the supplies and equipment to successfully sustain further penetration into Mexico. He therefore ordered his men to disband and return to Texas.”

On December 8 an additional number of soldiers, under 200 men, left Zapata to return home. Unfortunately a number of the soldiers felt betrayed and opt to continue their fight against the Mexicans. 304 soldiers including Captain Cameron’s company came under the command of Colonel William S. Fisher.

On December 19 these men crossed the river to the Mexico city of Guerrero opposite Zapata. Here they captured some boats and floated downriver to Mier where they levied the citizens for supplies, arms, and ammunition. They were promised some and then held the alcalde of Mier as hostage to ensure delivery. What they received was an unexpected response, for on Christmas Day General Pedro Ampudia, and Antonio Canales, a former commander of Cameron’s, arrived at the city with 700 Mexican soldiers.

Ampudia was commander of the units of the Mexican army stationed at Matamoros at the time of the Somervill Expedition. He refused to deliver anything to the Texans. There then ensued a pitched battle. Captain Cameron and his company occupied a yard about a block away from the city plaza. It was surrounded by a stone wall. The remaining Texans were on the fortified roofs of buildings facing the plaza and opposite the old church.

Cameron planned ahead for the upcoming confrontation. He had his men pile up baseball-sized stones beside their positions. These were to used to strike any enemy soldiers who might breech the defense while the Texans were reloading. When the first wave of attackers did breech the defensive line, the stones were used, and they proved very effective in that the initial charge was repulsed.

Some Mexican soldiers were actually killed by the thrown stones, however Cameron lost three men and seven were wounded. This is very likely an exaggerated number. Ten Texans had been killed in the fight and 23 wounded, some very badly. This conflict was later termed “The Battle of Mier.”

General Ampudia sent Dr. John J. Sinnickson, who had been captured while attending to wounded Texans, under a white flag of truce to the Texas soldiers. He wished to convey this message to Colonel Fisher “Say to Colonel Fisher that he must surrender with his whole force in five minutes or I will cause them all to be put to the sword and give no quarter. To accomplish this I have 1,700 regular troops and look every moment for re-enforcements of 800. If they surrender they shall be treated with all the humanity and deferences due them as prisoners of war. I will use my influence to keep them from being marched to Mexico city until they can be released or exchanged.”

Colonel Fisher, being a realist about the Texans’ dire predicament wished to surrender, even as Mexican soldiers advanced while the flag of truce was still waving and General Thomas Green fired on the advancing Mexicans. Despite additional assurances from other Mexican officers with whom Fisher had once served, the great majority of Texans said that they would never surrender.

Cameron formed his company in line under General Green and asked Fisher to step aside so his men could open fire on the Mexicans advancing from the west. While Fisher refused to do so the Mexicans retreated voluntarily but had already gleaned information about the size and condition of the Texas defenders. Some Texans conceived the idea that they might be able to make a dash for freedom using Alcantra Creek as cover. Only two were eventually escape from Mier to the Texas side of the river.

Fisher left to talk to General Ampudia and upon his return learned that all the men, except 20, agreed not to surrender. Fisher said he would then go alone to the Plaza to initiate a surrender. Half of the Texans joined him then the other half. Conceivably the Mexican forces numbered 2,340 consisting of the Zapadoras Battalion and the Yucatan 7th and 12th Regiment, and a company of artillery. One report states that 600 Mexicans were killed in the two day Battle of Mier.

General Green put the number at between 700 and 800. Mexican figures were considerably lower at 430 killed and 230 wounded. Later the Texans were to claim that only 460 Mexican regulars marched the 223 surrendered Texan soldiers to Matamoros and had even required General Canales’ mounted militia to re-enforce them.

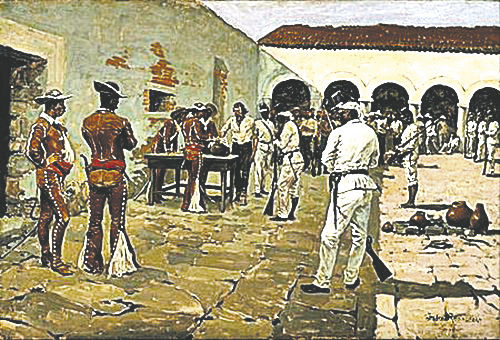

The invaders were initially sentenced to death, but this command was later reversed by General Ampudia on December 27. Once in Matamoros the prisoners were placed in filthy corrals at night with no shelter from the winter rains. That was only the beginning to their depredations.

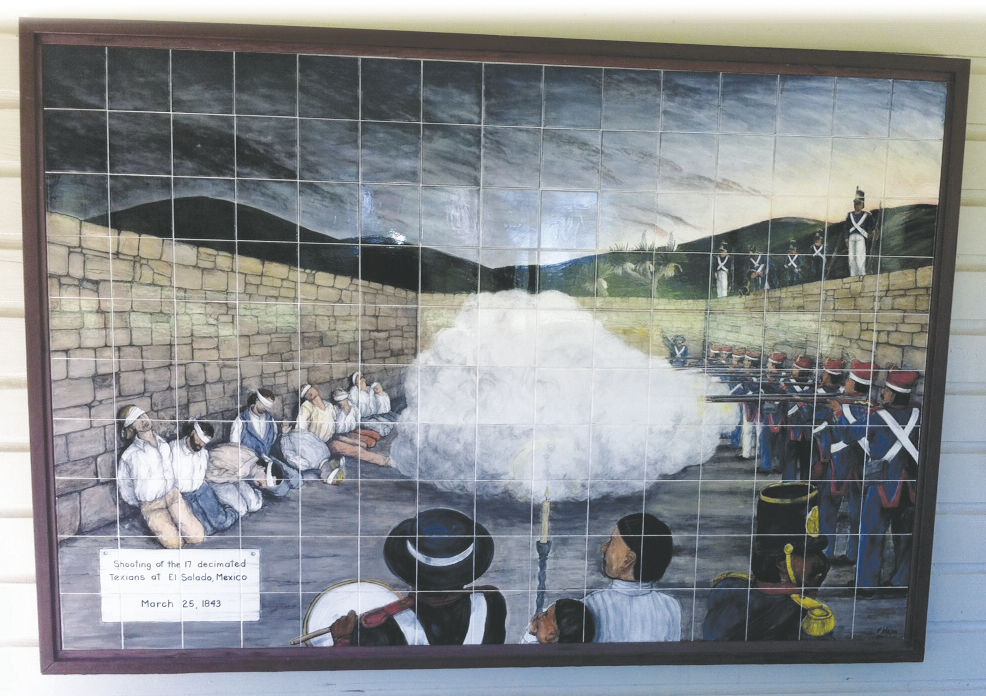

They were marched to Cerralvo, a distance of about 161 miles. On this march their shoes gave out. They were allowed a fifth of a ration of beef on meat days and about a half-ration of bread.

On other days they ate potatoes, gut, tripe, beef-head, liver, and heart. If being a prisoner was extremely taxing both in the physical and mental sense, more was still to come.