BY NORMAN ROZEFF

Various media in 2016 proclaimed the revival of super woman. In fact super women have always been with us in American affairs.

To name but a few there was Abagail Adams, Molly Pitcher, St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, Sacajawea, Sojourner Truth, Dorothea Dix, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Susan B, Anthony, Harriet Tubman, Clara Barton, Carry A. Nation, Jane Addams, and, of course, the numerous women currently serving as presidents or chief executive officers of large corporations.

The Valley has experienced its own super women. These include Salome Balli McAllen, Henrietta Chamberlain King, Mary Holdsworth Butt, Gladys Sams Porter, Rosa Maria Hinojosa de Balli, Francita Alvarez, and Paula Taylor Loyola among others.

However, the one gleaning the most attention is Sarah Bowman, better known as “The Great Western.” Hers is a story bordering on the fictional.

We don’t know her exact birth year, but it is placed in either 1812 or 1813, though census records note a Sarah Knight born as late as 1818 in the state of Tennessee or Clay County, Missouri. [I was unable to find this particular record on Ancestry. Com].

This is but one example of her story entwining both fact and myth. It was said that “she received no formal education and was believed to be illiterate, however she was unusual in being an American woman who (later) spoke fluent Spanish.”

One chronicler records that she began her career as a camp follower with her first husband during the Seminole War in Florida, though this chronicler states that there are is no records to back this up. However one Ancestry. com item shows a Sarah Knight marrying James McLin in Clay County, Missouri on 14 March 1841, and Fold 3 records do show a James S, McLin as a Tennessee Infantry private in the early Indian Wars.

Under Army rules in place before the Civil War, women married to soldiers could follow the troops. They helped with meals, washed clothes and tended to the sick and wounded. If McLin is not the soldier with whom she attached, it is alternately written by another historian, “A strong-willed woman, she participated in the Florida campaign against the Seminoles, later marrying a man who admired her boundless spirit.”

By 1845, she was following Zachary Taylor’s troops as they assembled at Corpus Christi before the start of the Mexican War and was married to her second husband, a soldier whose name has been spelled Bourdette, Bourget, Borginnis and Bourkyte. He apparently enlisted at the Jefferson Barracks, Missouri.

At this point she became known as Sarah Borginis. J.F. Elliott writes in the Journal of Arizona History that “The man was probably Charles Bourgette of the Fifth Infantry [another source says Eighth United States Infantry], but he remains a shadowy figure, and his relationship with Sarah was less than permanent. Sarah was always looking for new romantic mountains to climb.”

Despite whatever had transpired Sarah had become an outspoken supporter of Taylor as she was already confident of his leadership skills which she had observed in Florida.

Numerous descriptions vary as to her physical appearance, but all agree that she was a woman of large proportions. She was tall, at least 6 feet and possibly even 6 feet, 2 inches. She weighed over 200 pounds. Despite her considerable size, this strapping, muscular woman was said to have an hourglass figure and, despite her strength and pugnacity, was quite graceful. This fiery woman had long dark red hair to match her temperament. Her eyes were grey-blue in color.

Sarah signed on as a laundress and cook with General Zachary “Old Rough and Ready” Taylor’s army in Corpus Christi. In Corpus Christi she cooked for the officers’ mess. On the journey to the Valley she may have had her own wagon. Once on the north bank of the Arroyo Colorado Taylor’s force hesitated in crossing as Mexican soldiers on the south side were using a ruse.

They were moving side to side playing military bugle calls related to troop movements. In actuality the Mexican military force on the south side was scant. The Handbook of Texas Online relates, “Sarah first distinguished herself as a fighter at the crossing of the Arroyo Colorado in March 1846, when she offered to wade the river and whip the enemy singlehandedly if Gen. Williams Jenkins Worth would lend her a stout pair of tongs (apparently referring to pants with two legs)”. She was also quoted as making this statement at the time, that after wading across the stream she would “whip every scoundrel that dare show himself.”

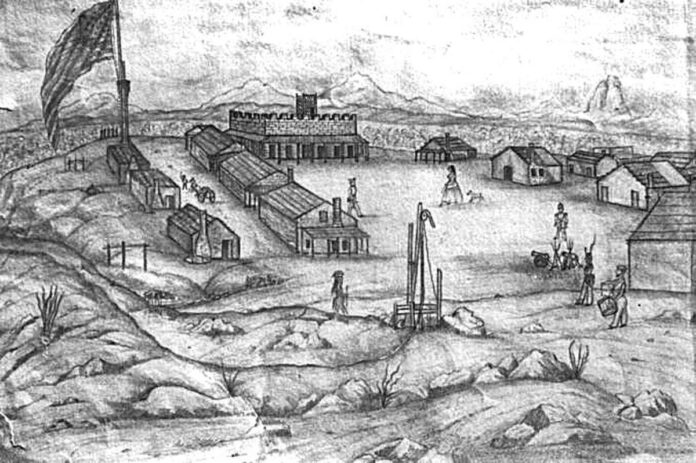

Once reaching the Rio Grande and before moving on to Point Isabel to retrieve supplies that had been landed there, General Taylor was to order the construction of Fort Texas across the Rio Grande from Matamoros . It was manned by 500 men of the 7th Infantry with Major Jacob Brown as the regiment commander. This regiment had earned the nickname of the “Cotton Balers.”

During the War of 1812 these troops had made an heroic defense behind cotton bales in the Battle of New Orleans. Later during the siege of Fort Texas (renamed Fort Brown after its commander, Major Jacob Brown, was killed there under a Mexican artillery barrage from Matamoros) Sarah exhibited extraordinary bravery that would warrant her the nickname “The Heroine of Fort Brown”. The New Orleans Delta newspaper ran a short news piece recounting the circumstances surrounding the toast made by a Lt. Bragg at General Arista’s headquarters in Matamoros, then occupied by victorious U. S. forces.

It read, “The Heroine of Fort Brown He said that during the whole of the bombardment, the wife of one of the soldiers whose husband was ordered to Point Isabel, remained in the Fort and though the shot and shells were constantly flying on every side, she disdained to seek shelter in the bombproof but labored the whole time in cooking and taking care of the soldiers, without the least regard for her own safety. Her bravery was the admiration of all who were in the Fort.” The fact was that she kept operating the officers’ mess for a week “even when a tray was shot out from her hands; even when a fragment pierced her sunbonnet.”

Elliot would add “she set up her kitchen in the thick of battle as an American fort was being shelled. She fed the troops, took a bullet in her bonnet, tended the wounded, found a musket and stood ready to “man the ramparts if the Mexicans assaulted the fort.” Sarah, had in fact, ignored orders for the wives to retreat underground and instead she set up a kitchen in the yard, delivering food and buckets of coffee to soldiers defending the rampart walls.