HARLINGEN — This is a story about twin bridges built within two years of each other, and located just 32 miles apart.

Both span the Rio Grande, linking the United States and Mexico.

And that’s where the similarities end.

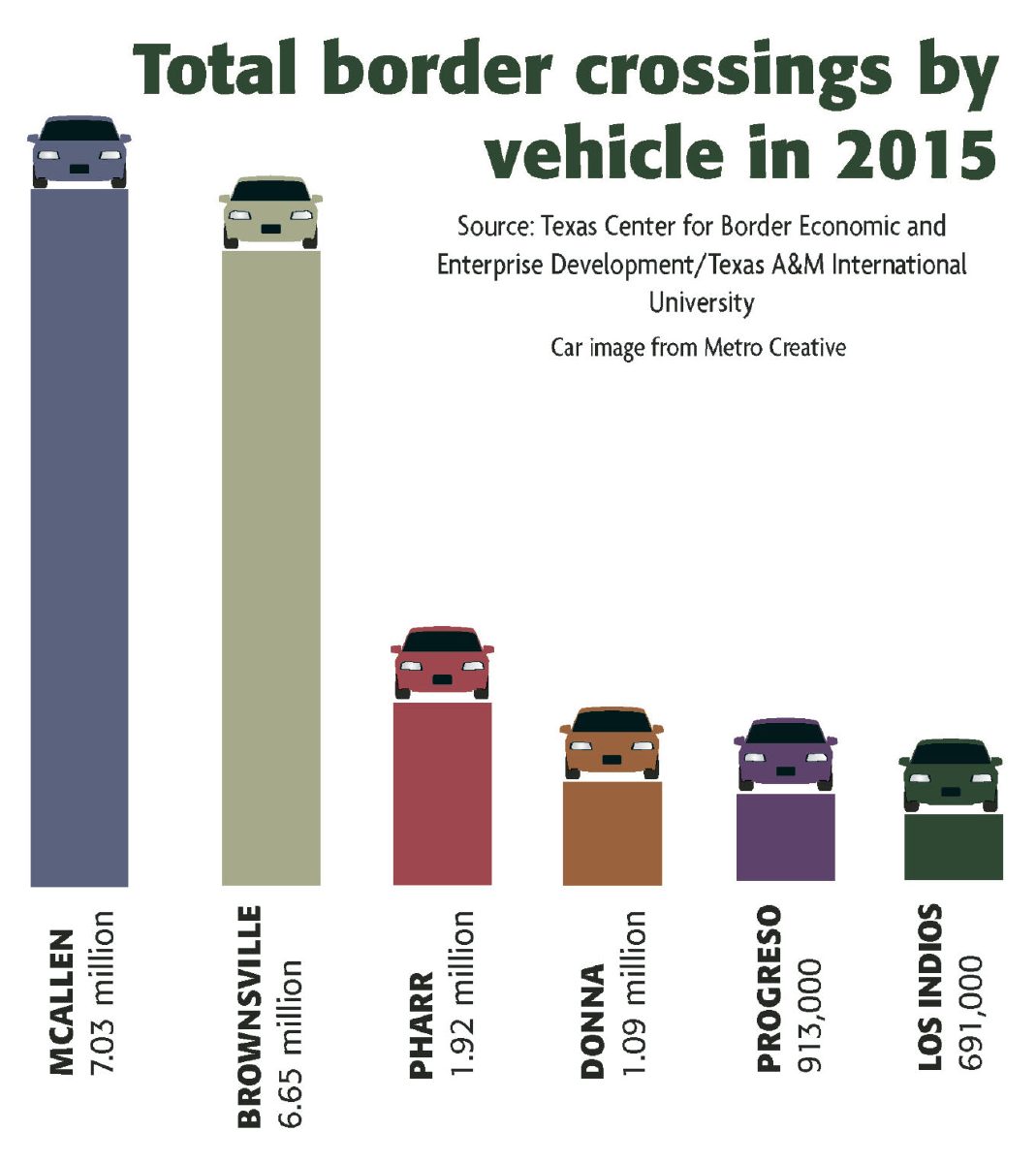

The Pharr bridge, officially the Pharr-Reynosa International Bridge which opened in 1994, is a booming facility with truck and vehicle traffic last year totaling 1.92 million. From those vehicles, the bridge generates about $12 million in annual toll revenue.

The Free Trade Bridge at Los Indios opened in 1992, and last year had 691,000 vehicles cross. It generates just over $2 million in annual tolls for its owners, the cities of Harlingen and San Benito, and Cameron County.

What accounts for the disparate performances of the two bridges can be chalked up to some early canny decisions in Pharr, some good geographical luck and, in the case of Los Indios, more than two decades of neglect.

Raudel Garza, now chief executive of the Harlingen Economic Development Corp., worked for Pharr’s economic development team about the time their bridge opened.

He recalls a crucial decision made then.

“I can remember when the Pharr bridge and the Los Indios bridge opened up basically at the same time, and neither of them had any infrastructure on either side,” he recalled at a recent HEDC meeting.

“But Pharr brought in a temporary building which was really an old classroom, one of those portable buildings,” he said. “They put phone lines into that building, and they air-conditioned it, and told customs brokers come in and use that space, you can have a space to process your paperwork.

“And they did.”

The decision to offer portable classrooms to customs brokers served as the catalyst for a network of brokers on both sides of the border. It also served to jumpstart the addition of critical infrastructure on both sides, too.

To be fair, Pharr always had a big advantage over the Los Indios bridge site given the proximity of the major Mexican city of Reynosa situated just across the river. But at the time, there was little in the way of infrastructure to support the bridge crossing in either country.

“There were several industrial parks south of the Pharr bridge, but even when the Pharr bridge was being constructed, there wasn’t a whole lot of development to the east of the Pharr bridge,” Garza said later in an interview.

“Now it’s all over, all around it,” Garza said.

Garza said either Reynosa or the federal Mexican government devised a plan to connect the international bridges because all the truck traffic to that point used to cross at the McAllen-Hidalgo bridge.

Now much of it goes to Pharr.

“Reynosa has a loop; Matamoros does not,” Garza said of the major Mexican metropolitan area closest to Los Indios.

“Some of the industrial parks on the west side (of Reynosa) connected to the Pharr bridge,” he said. “Some of them would take the loop and get to the Pharr bridge that was right there, others would kind of work their way to the Hidalgo bridge and that new road connects that directly.”

But success of the Pharr bridge was by no means assured in the early years, and Garza recalls there were some misgivings about the $20 million or so in bonds which were taken out to build it.

“I remember even up to 1996 that the finance department guys were all very nervous about debt payments coming on and whether or not they’d be able to meet the debt payments,” he said.

“Now they’re cranking out $12 million a year” in toll collections, he said.

After nearly 25 years, officials on both sides of the border are playing catch-up to entice more traffic across the Los Indios bridge, which cost $40 million.

The consensus is, if the infrastructure is built, they will come

On the U.S. side, Panasonic has warehouses near the Los Indios bridge in an industrial park, as does Penske Logistics. And a new cold storage facility to store produce is planned, along with a new Border Facility Inspection Station run by the state of Texas to inspect trucks for safety violations as they enter the country.

On the Mexican side, whether due to security concerns about drug cartel violence or to investment decisions made by financiers, the infrastructure has not arrived.

“I think it’s just going to take somebody who wants to invest the capital to put a park (industrial) over there and we haven’t found the right person,” said Harlingen Mayor Chris Boswell.

“Until they put a park over there, it’s going to be really hard, and we keep hearing one of the reasons for some, if not everybody, but some of the people don’t want to cross that bridge for security reasons,” Boswell added.

The cities of Harlingen and San Benito, as well as Cameron County, are big stakeholders when it comes to the Los Indios bridge. Economic development officials are seeking to find ways to increase infrastructure around their investment.

“There are a couple of really nice industrial parks that are only 10 miles away” from the Los Indios bridge, said Lupita Gutierrez-Garza, chair of the Harlingen EDC’s board.

“There is some development there, but those developers have offices in McAllen (and Reynosa), they do not have offices in Cameron County,” she added.

Gutierrez-Garza suggests using HEDC funds to set up incubators to provide office space for these businesses, which would “lead prospects and channel prospects to that area.”

“That’s something that needs to be talked about from a logistics perspective, and I’m not talking about truck logistics, I’m talking about logistics on investment and how best to maximize that investment,” she added.

Officials on the U.S. side of the border say newly elected office-holders in Mexico, including the Tamaulipas state governor, Francisco Garcia Cabeza de Vaca, are still finding their way.

As a result, some negotiations on cross-border issues, like BiNED, the regional economic development initiative involving officials in both nations, have been delayed.

U.S. officials say the early relationships with the new Mexican office-holders seem promising, and they hope to accelerate efforts to fully establish BiNED as well as create infrastructure around the Los Indios bridge.

But Boswell, among others, is looking for more than just increasing border crossings.

“Trucks passing through don’t really do that much for you,” the Harlingen mayor said. “Whoever owns the bridge gets a fee from it, but in terms of increased economic activity, they just tear up your roads and they go north and they move a product to have it distributed.”

Boswell says the greater need along the border is manufacturing, not truck traffic. He notes that many multinational corporations are “nearshoring,” or bringing manufacturing plants back to Mexico from China, because it’s become cheaper to operate them in Mexico.

“But they’re locating them in the interior instead of on the northern border, where we would stand to benefit more from increased economic activity,” Boswell said.

He notes that BiNED initially was intended to procure infrastructure to boost border crossings at Los Indios, although since then the still-forming BiNED appears to have broadened in scope.

“Hopefully, Los Indios would be a catalyst or at least a first model of how it would work,” Boswell said. “But the idea behind it is to have sort of an area that doesn’t have a border.

“You utilize the natural advantages of both countries, using the capital on the U.S. side and the labor on the Mexican side,” he added.