BY NORMAN ROZEFF

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the final part in a three-part series by Norman Rozeff. The first two parts can be found at www.ValleyStar.com.

It was Dr. Carlos Juan Findlay, of Spanish-Cuban heritage, who in 1881 Cuba theorized that mosquitoes might be the vector of yellow fever. Major Walter Reed, working with American occupation forces in Cuba following the Spanish-American War, was to confirm this in 1900.

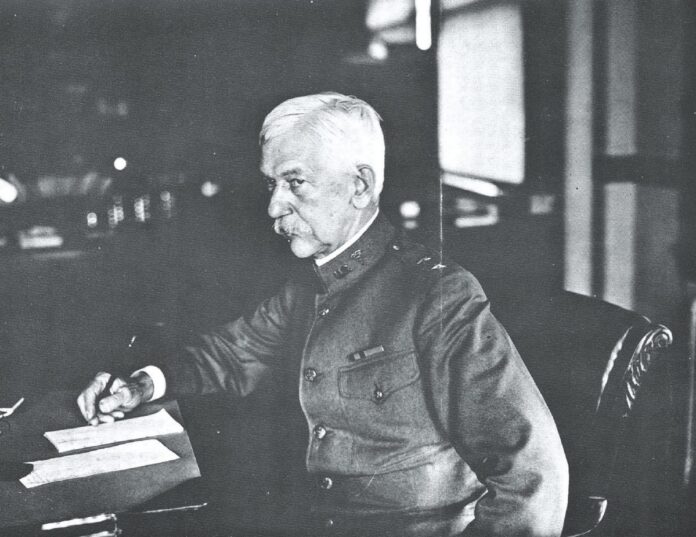

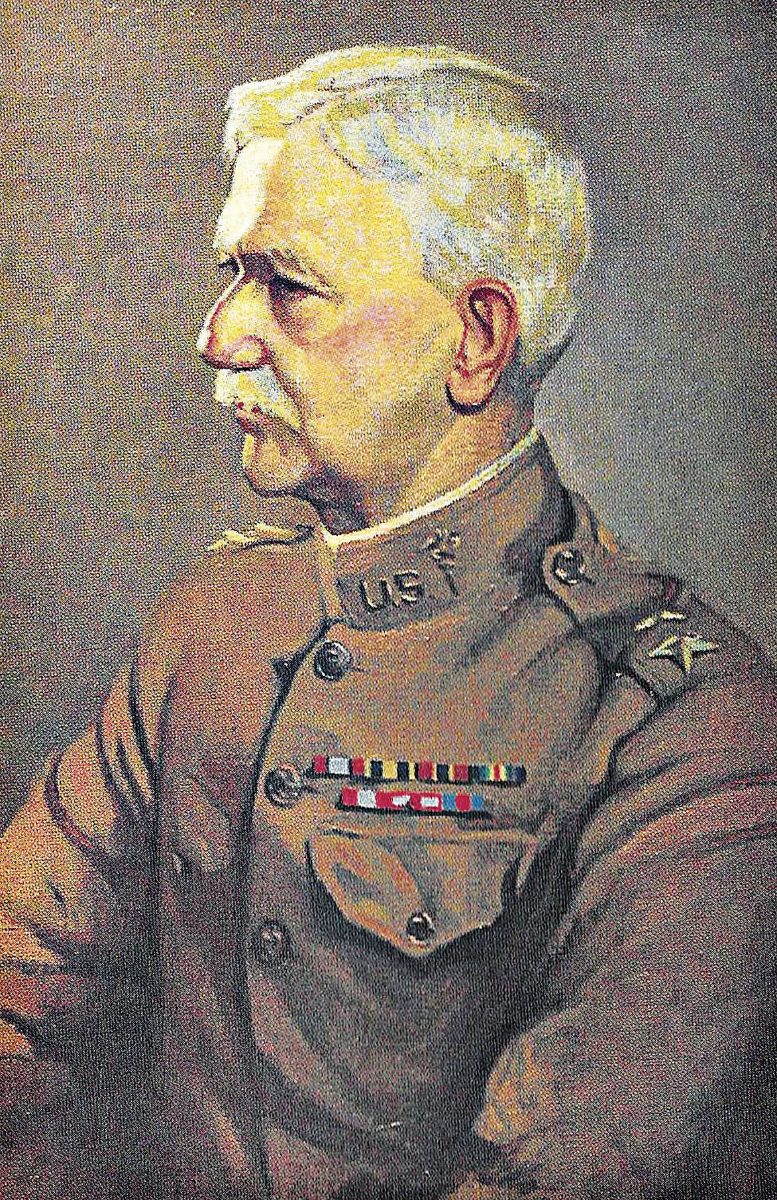

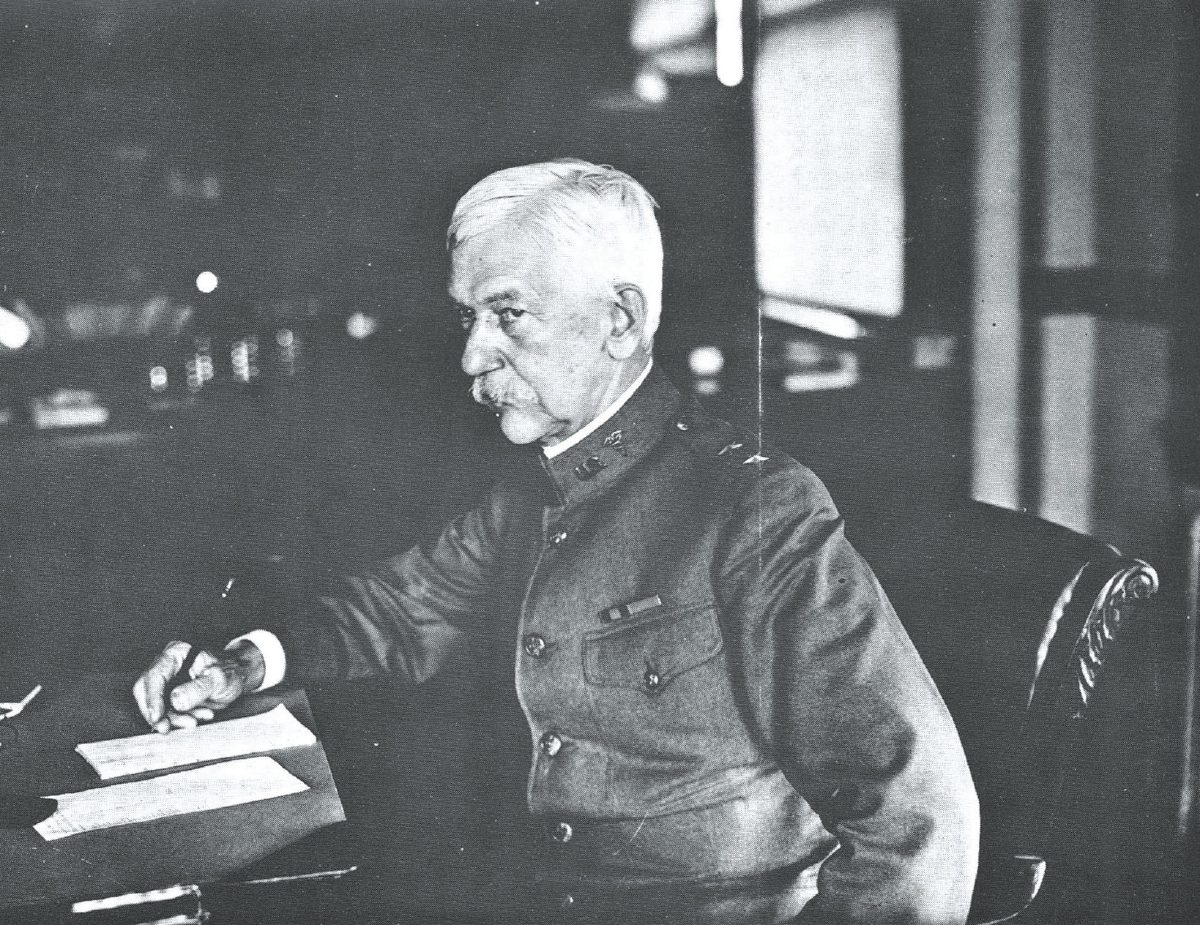

The Gorgas Science Foundation (GSF) was established in Brownsville in 1947 by Texas Southmost College Biology Professor Barbara T. Warburton. From it we learn the following information about Gorgas:

“William C. Gorgas served at Fort Brown (now UT-Brownsville) from 1882-1884. While there, he was stricken with yellow fever, leaving him immune. Gorgas read the research of Carlos Finlay and Walter Reed linking malaria and yellow fever to the Aedes aegypti species of mosquito. He conducted his earliest yellow fever research while at Fort Brown. Later, while in Havana, he helped end a city-wide epidemic by draining mosquito breeding areas.

“In 1902 Gorgas left Havana for the Panama Canal construction, an area where yellow fever had decimated those laboring to build the canal. He brought the disease under control within 18 months using similar mosquito control techniques. Later he served as Surgeon General of the United States Army.”

Gorgas, when younger, had sought to attend the Military Academy at West Point. He was denied this opportunity as his father had fought on the Confederate side. He then enrolled in the Bellevue Medical School in New York City. In the year 1880 he enlisted in the U.S. Army as a doctor. He served at Fort Clark in Kinney County, Texas before being assigned to Fort Brown.

Gorgas was given specific instructions not to come in contact with yellow fever victims. He disobeyed these orders and narrowly escaped being court-martialed for his intransigence. He placed himself at risk and was to contract the disease.

Among the patients who he had treated was Marie Doughty, who was stricken while visiting her sister, who was married to a Fort Brown officer. Marie in turn would nurse Gorgas when he was taken with the fever. They would later marry in 1885.

Logan Hawkes delves deeper into Army Assistant Surgeon First Lt. William Cameron Gorgas’ history and tells us:

“It must have brought great pleasure to young Army surgeon Lieutenant William Gorgas, freshly assigned to such a prestigious facility. Gorgas was a ‘new age’ physician for his time, a scientist as much as a doctor, and it may not have been an accident that he arrived about the same time as a great yellow fever outbreak on the border.

Defying orders to refrain from treating the stricken because he had never had a brush with the disease and therefore was not immune to the virus, Gorgas spent relentless nights and days treating the afflicted. Worse, in the eyes of his commanders, Gorgas was conducting postmortem studies on diseased victims.

“When his experiments were uncovered, he was arrested and very narrowly escaped a court martial by explaining his research — an effort, he said, to thwart the disease if not develop a permanent cure. But Gorgas had alienated his superiors and the damage to his service record had been done. Carving the dead was paramount to heresy in their eyes, and eventually he was reassigned to Cuba, where he continued his research into yellow fever, this time more careful to conceal his unusual postmortem practices …

Eventually, Gorgas confirmed that yellow fever, and many other disease, were being borne by mosquitoes, and it was his sanitizing efforts to eradicate mosquito populations that eventually led to the control of the disease world wide.”

During and after the Spanish-American War disease was decimating U.S. Forces in Cuba. There were 968 combat deaths in the war and over 5,000 soldiers died of yellow fever whose mortality rate was 85 percent. While on the island the 24th Infantry, an African-American regiment, was sent to the Seboney Hospital to care for the sick. In 40 days more than one-third of the regiment of 460 died of yellow fever and malaria.

It was in 1898 at the end of the Spanish-American War that Gorgas was appointed Chief Sanitary officer in Havana. During the war 600 out of every 1,000 soldiers came down with the fever. The doctor cleaned up much of the filth existing in Havana, but by April 1900 the fever returned to that city as filth alone was not the prime transmittal mechanism.

Gorgas started his anti-mosquito campaign in Havana in 1901. It was made a crime to allow mosquitoes to breed on one’s property. Gorgas oversaw crews to pour oil on the tops of cisterns throughout the city, inspect premises to detect breeding grounds, ordered land drained, stocked ponds with larvae-eating fish, educated the public, screened sick rooms, and covered patients with mosquito netting. His methods worked well and yellow fever in Havana became a thing of the past.

As chief sanitation officer in the Panama Canal project Gorgas went on to accomplish the same feat in 18 months. The previous efforts by the French to build the inter-ocean canal had been stymied by the disease situation when more than 22,000 men died, so Gorgas’ efforts were monumental in scope. In 1913, just before the completion of the canal, President Woodrow Wilson named Gorgas to the position of Surgeon General of the United States. Gorgas was to die July 3, 1919. Today there is a modest plaque on the TSC Administration building. It reads:

WILLIAM CRAWFORD GORGAS

1854-1920

In this building, formerly the Post Hospital, in August 1882, Major General William Crawford Gorgas, Surgeon General of the United States, the First Lieutenant Assistant Surgeon first studied Yellow Fever. Largely through General Gorgas’ work, the cause and prevention of Yellow fever were discovered.

Placed by the Brownsville Historical Association

December, 1948

Many a grave marker at the Old Brownsville City Cemetery attest to the impact of the yellow fever epidemics that once plagued the town through decades of its existence. As noted in Eileen Mattei’s book For the Good of My Patients, the History of Medicine in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, 31 pages of burial records for the Brownsville Cemetery indicate that 1,500 died of the fever. The last major yellow fever outbreak in the United States occurred in 1905 when 437 people died in New Orleans. This major port city had seen a total of 41,000 yellow fever deaths in the period 1817 through 1905.

If the fever has been minimized by vaccines and sanitation, the same cannot be said of its vector Aedes aegypti. It is currently termed “Cockroach of Mosquitoes” in deference to the cockroach’s long history on the planet and the same holding true for A. aegypti. It’s a tough customer with which to deal.

It bites during the day and hides at night such as in closets and under beds. Even under dry conditions it may sustain itself as its eggs can survive for months in a desiccated form.

With the Zilka virus spread by this mosquito making the daily news, control of this pest is being put on the front burner. Some of the methods being weighed are: sterilizing male mosquitoes with radiation, genetically engineering mosquitoes, infecting mosquito eggs with Wolbachia bacteria, and older standby such as eliminating standing water, removing trash and water containers from homes, spraying insecticides inside and outside homes, and treating breeding spots with larvicide. Obviously Man versus Nature is a never-ending battle.